Lucy and Eliza Kennedy

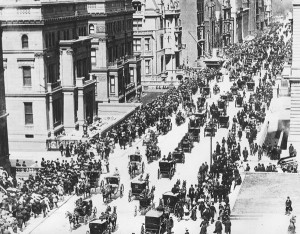

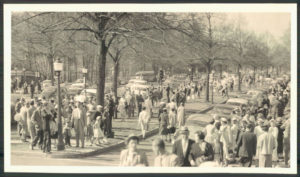

My wife is from Pittsburgh, and her grandparents there were staunch Scots Presbyterian Republicans, who always cast a suspicious eye upon the doings of the Democratic political machine. Grandmother Eliza Kennedy (Mrs. R. Templeton Smith) was an important suffragette. She thought women would clean up politics. After she got the vote, she discovered how corrupt politics was, and she and her sister Lucy Bell (Mrs. John Miller) made life miserable for the Democratic machine in Pittsburgh. Entrenched politicians called them “she-devils” because of their unrelenting efforts to expose corruption at city hall.

The Democrats were known (I am shocked, shocked) to finagle the voting rolls so that the dead and nonexistent would vote Democratic, but they had to reckon with the eagle eyes of Eliza and Lucy. Once the sisters were going over the electoral rolls to challenge the invalid names. After a long and trying session, Eliza put down her papers and exclaimed “Fini la guerre!’ Lucy responded “Finney Lagair? I don’t see him on my list!”

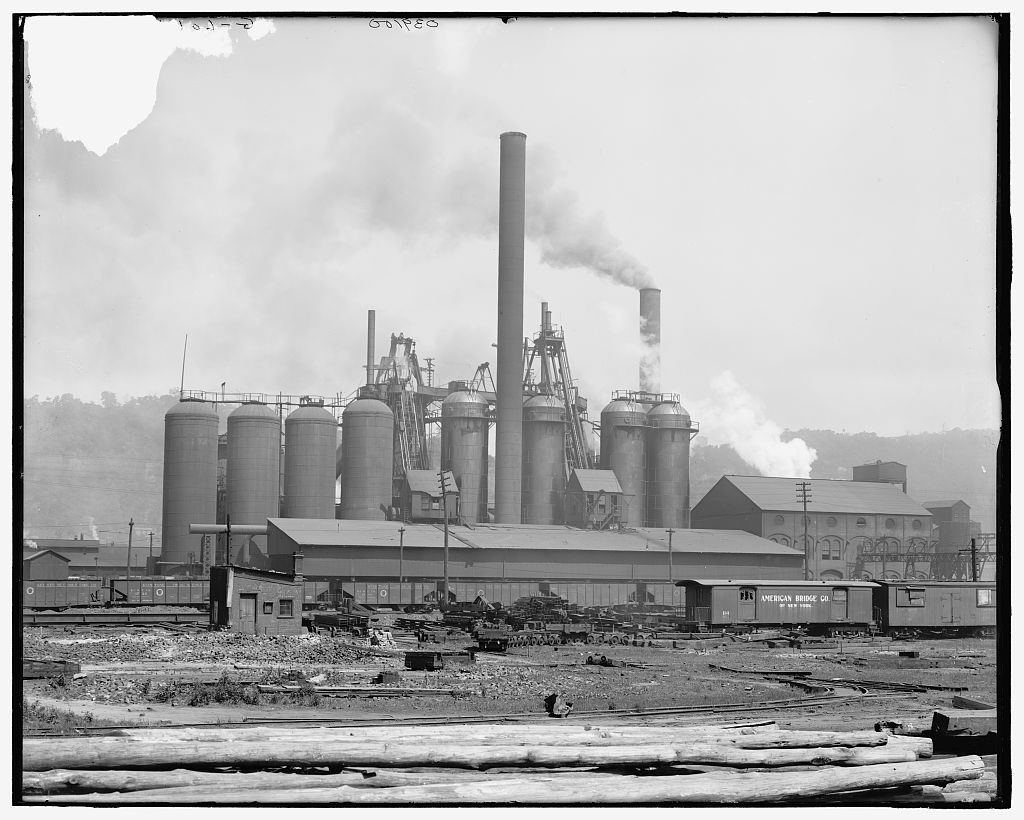

Eliza went to Vassar and majored in calculus. Her father was Julian Kennedy, who went around the world building blast furnaces for Andrew Carnegie. He affectionately named his blast furnaces after his daughters, a gesture that would have been understood by Pittsburgh politicians.

Lucy