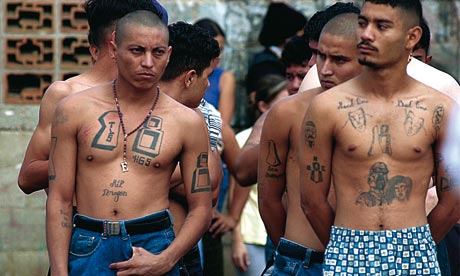

Latino men have the reputation for being detached from the church, and too many of them are caught up in destructive macho and gangster cultures.

Both Catholics and evangélicos (conservative Protestants, fundamentalist/Pentecostal) try to reach them; I have wondered who has the better success.

John Wolseth lived in Honduras and studied a barrio with gangs, Catholic Base Communities, and evangélico (Pentecostal in this barrio) churches. He describes and analyzes that environment in Jesus and the Gang: Youth Violence and Christianity in Urban Honduras.

Progressive Catholicism emphasizes community and solidarity with the poor and blames the problems of the poor on structural inequities, especially economic oppression. Catholic youth groups in the barrio follow this analysis and try to identify with the poor. But they are fearful of identifying with the poor who are gang members. Catholic youth blame gangsterism on social inequities, but do not explain why they themselves have not followed the path of the gangsters.

Pentecostals set up a harsh dichotomy between the world ruled by Satan and the church ruled by Christ. Young men who want to give up the destructive and self-destructive life of the gangs can have a conversion experience and dedicate themselves to a new life, totally rejecting the old one and separating themselves from it. They have to change their lives to convince both the church and their old gangs that they are cristianos. If a man leaves a gang, he is killed by the gang, unless he becomes a cristiano. Gangs usually let Pentecostal former gang members alone, if the former members demonstrate that their lives have really changed. Perhaps it is from superstitious motives, but at least the gangs let them go.

Catholics, with their rhetoric of solidarity, do not offer gang members the opportunity for a clean break that Pentecostals offer. Catholics blame society for individual problems; Pentecostals stress individual responsibility. Wolseth blames Neoliberalism and American interference for most of Honduras’ problems (and therefore agrees with progressive Catholics), but admits that Pentecostals help some individuals escape from the most destructive consequences of broader social problems.

Perhaps in Latin cultures, Catholics cannot do this. Catholicism and the culture are so entwined that becoming a fervent Catholic does not offer the same sort of break that gangsters need. Pentecostals, as they reject both destructive machismo and most specifically Catholic practices – mass, statues, procession, rote prayers – are foreign to the general Catholic-based culture and therefore can offer gangsters the clean break. (This is my analysis)

The same dynamic seems to be at work with the older married men that Elizabeth Brusco describes in The Reformation of Machismo: Evangelical Conversion and Gender in Columbia. The general culture includes both machismo and Catholicism. When men become evangélico, they reject both Catholicism and machismo. They follow a biblical pattern which makes men responsible heads of household. Catholics of course would like men to abandon machismo and become responsible husbands and fathers, but they do not seem to be able to offer the clean break that men need.

When Catholic families get some money, the first thing they buy is a radio; when evangelical families get some money, the first thing they buy is a dining room table. Protestantism more than Catholicism has stressed the importance of the family in the Christian life, sometimes to the extreme. I think C.S. Lewis said that sometimes Protestants set up the dichotomy of the family vs the world, rather than the kingdom of God vs the world. But on the whole, stressed modern cultures need a strong emphasis on the family, and conservative Protestantism seems to have had some success in helping people follow the biblical model.

If anyone has any observations on this, especially from what they have experienced or seen, I would appreciate them.

Here in Estancia, New Mexico we have a lot of gangs and machistas. In 1972 50 of the our town’s most rebellous youth started walking over 100 miles in a pilgrimage to the sacred shrine of Chimayo with Father Michael O’Brien our pastor.. Today there are tens of thousands who do that each lent. At that time the movie “Convoy” starring Kris Kristoferrson was filmed in Estancia which was supposed to be Alvarez, Texas in the film, or “trucker’s hell”. The yearly walk to Chimayo was a bold act of machismo and brotherhood. To have walked in that pilgrimage was a mark of manhood. It reminded some of them of the Bataan Death March that their fathers and uncles had endured. The walk was a rite of passage, a challenge, a discipline which earned respect for themselves, their families and their community and their culture. Just like Jesus and his “gang” of disciples they walked the walk so they could talk the talk.

Leon,

Though I have no experience with Latin America, I have experienced this great disconnect in other ways. I grew up Catholic, became an evangelical in college, was ordained as an evangelical Episcopalian minister and in my late 30s returned to the Catholic Church. Despite alot of brave talk, I’m willing to bet that most evangelicals who become Catholic suffer a great deal of pain from the profoundly different culture in the Catholic world. For example, my parish has a “justice” ministry that absolutely bewilders me. It seems to me far from the sort of Christ-centered ethos of the evangelical world–more of the Democratic Party screaming for handouts and blaming everyone else for the problems in the world. It is so disgusting and disheartening.

dr. T, can you not start your own group? I agree with your assessment….we have been the object of a hostile takeover.

Dr T,

I know exactly where you are coming from. I’m a former evangelical and Episcopalian, Catholic since 2007. The Church is both the best thing of my life, and the most frustrating train-wreck of my life.

The only really transformational possibility I’ve encountered is the work of the Catherine of Siena Institute. They call their program The Making Disciples Workshop.

I would very strongly recommend that you read, “Forming Intentional Disciples”, by Sherry Weddell. She explains many many things that have bewildered me.

Did you know over 40% of Catholics do not believe it is possible to have a personal relationship with God? And many of the rest do not actually have such a faith? Most of the Catholic leaders she’s asked estimate that maybe 5% of their people are disciples!

Leon, I seem to remember you or someone recommending that the Eastern Rite be introduced into Latin America in order to make possible a married priesthood and present a different form of Christian culture. Any thoughts?

I agree with Dr. T above. Large numbers of Catholics seem like so many members of other mainline Churches, they are Christians doctrinally (maybe) and morally, but appear to lack a personal relationship with and commitment to Jesus as Lord and savior.

Social justice then becomes an exercise in progressive politics and not the spreading of Christ’s reign and kingdom. I remember Dorothy Day (who evidenced a deeply personal relationship with Christ) saying the point of social justice is to create a society where it’s easier for people to be good and follow the Lord. That includes a more just economic system but also better moral standard. It overlaps with some or much progressive thought but also differs on many points (abortion for one).

In el Salvador, a lot of gangs members become ‘born again’ for a little while visiting and congregating with protestantes as we called all of them (evangelicos, pentecostales, protestantes etc). But after some time they go back to their old ways.

In HULU u can watch 4 free the movie ‘La Vida Loca’ about gangs in el Salvador.

http://www.hulu.com/watch/397077

Fr Michael,

Your assessment about social justice

becoming an exercise in “progressive politics” hits the mark . A prime example of this would be what some now consider today to be “human rights”.Using politics to change the traditional teachings of the Church Fathers on Christian moral doctrine is intended to destroy the Church by redefining the Gospels to justify sin under a false notion of charity.

The same political agenda that made abortion legal is heavily financed by those who wish to create even more “progessive” laws.

http://www.victoryinstitute.org/home

Dr. T and John Weidner, I heartily recommend to you the following blog, “Don’t Convert,” written by a former evangelical who regrets becoming Catholic (dontconvert.wordpress.com).

John, you shouldn’t be surprised that most Catholics have no idea what a “personal relationship with God” means or entails. For one thing, Catholicism has become so imbued with esoteric, academic theology that the simpler aspects of the Gospel have been buried under geological layers of such theology. For another, Catholics (especially Traditionalists) have been brainwashed (and I don’t use that term lightly) into thinking that it’s the Church as an ecclesiastical institution that matters and it’s the institutionalized Church that serves as the intermediary between Christ and the believer.

Leon, regarding Catholic rhetoric about “the poor,” have you noticed that Catholics make no demands upon the poor nor hold them accountable for their behavior? I think that’s a fundamental reason why evangelicals have far more success w/Central American gang members. Evangelicals demand a choice, a committment. I think it’s because they know the implications of Scripture far better and more thoroughly than Catholics.

Compassion is one thing but compassion without accountability is nothing but enabling.

Joseph,

I have not the slightest regret in converting, and I think and read about these issues all the time.

…imbued with esoteric, academic theology that the simpler aspects of the Gospel have been buried under geological layers of such theology.

Not true. I wish Catholics would pay much more attention to our theology, which is a mine of great riches.

And Catholic practice focuses too much on the institution, and too little on Christ. Absolutely true. But that is NOT the teaching of the Church, just bad practice. The book I recommended to Fr K is stuffed full of quotes from Popes, Trent, the Catechism and the documents of V-II that say that Christian faith must be personal faith in God, and specifically in Jesus. Give it a try, especially Chap. 4. It will blow you away!

The Church explicitly teaches, for instance, that the graces God gives us through Baptism can only be “activated” though active personal faith!

The Church explicitly teaches that the job of the faithful is to bring Christ to the world, and that priests and bishops are simply our servants, to help us in this, “…for the perfecting of the saints, for the work of the ministry, for the edifying of the body of Christ.”

I agree with you, Joseph, that demanding a choice, a commitment to change, is crucial. It is the essence of conversion. Our Amchurch tends to think of conversion as being flooded with happy feelings in a personal encounter with Jesus. The personal encounter is important, but it is a Presence that asks a questions and wants a decision. In my work, which is a Catholic recovery ministry, most of the programs or models are about feeling better. I have developed one that is based on making decisons in informed faith. You would not believe the difference in God’s response and people’s recovery!

Joseph,

The criticisms at Don’t Convert are most valid ones. I’m lucky to have a parish with great music and excellent preaching (Dominicans, the “Order of Preachers.”). But I’ve seen lots of the bad stuff. He has my sympathy.

BUT, you both seem not to be thinking clearly. If there’s a question of which church to belong to, then the only issue must be Truth. Not practice.

If you believe, as I do, that the Catholic Church is the church founded by Jesus, which has preserved and handed down the teachings given to the Apostles, then you must belong. Even if the abuses are ten times worse than what we see. You can complain, but you cannot say “Don’t convert.”

If you don’t believe that, then you are not a Catholic.

John, teaching isn’t just a matter of rhetoric but of practice, as well. Pope Benedict refused to rebuke publicly the president of the German bishops’ conference, who denied on German television the doctrine of propitiation. He also failed to rebuke Cdl. Wuerl for the latter’s refusal to implement Canon 915 in the latter’s archdiocese. Both Benedict and John Paul II failed or refused to discipline bishops who enabled sexual predators in the clergy.

Moreover, JPII arbitrarily undertook a revised, abolitionist policy toward capital punishment that contradicts not only centuries of teaching from Scripture and Tradition but his own catechism!! See also, http://archive.frontpagemag.com/readArticle.aspx?ARTID=1463

In addition, the Catholic Church (thanks to Nostra Aetate) views Islam as a fellow “Abrahamic faith” instead of as what it is: religious Nazism that justifies murder in Allah’s name. If that isn’t evil, then the word “evil” has no meaning.

I left the Catholic Church because it is effectively apostate. Its leadership no longer believe or practices what it teaches. Why does it deserve any respect, let alone allegiance?

Moreover, do you think that a holy, righteous God is pleased with the developments I’ve mentioned, even if His Son did found the Catholic Church?

I suggest you learn about the vision Pope Leo XIII had in the 1880s about the Catholic Church’s future, then get back to me.

One more thing, John: “Truth” does not reside in any institution but in one Man, Jesus Christ. Conflating His redemptive atonement and His conquest of death with any individual religious institution — Catholic, Protestant, Orthodox, whatever — is nothing short of blasphemy, mindless groupthink and, ultimately, idolatry.

The Church is NOT “any individual religious institution.” The Church is the Body of Christ, and existed before our universe was created. The Church was founded by Jesus. One Church. Not 30,000. And Jesus asked his followers to be ONE.

The Church as a human institution within the world is deeply flawed, and always has been. From the very beginning, from the moment the disciples deserted Jesus at his execution. You can spend your whole life bellyaching, and pile up ten-thousand valid grievances to numb your conscience. But that counts NOTHING towards the basic question. Which was expressed by St. Cyprian long ago…

“If a man desert the Chair of Peter, upon whom the Church was founded, can he be sure he is even in the Church?”

The ancient fathers said that the Church is ultimately composed of all the righteous since Abel. The earthly institutional element is flawed because it’s composed of human beings who are flawed.

Jesus is the center of my life, thought and existence. He is the one whom I trust and look to for salvation. But I know he wants me to be part of a people his Father is gathering and that on Earth, this people needs a visible structure and teaching authority. Bad as the institutional element appears (and often is), what’s the alternative? Sola Scritura? It makes no sense in light of the fact that it isn’t even mentioned in scripture. Not to mention that for the first four centuries Christians didn’t agree on what writings constituted the New Testament scriptures. And especially given that those who follow the idea have NEVER been able to agree on scriptures’ meaning with respect to very important points (does God want everyone to be saved or has he predestined some/many to be damned?; Is Christ present physically in the Eucharist or just spiritually or not at all?; Is salvation once for all or can it be lost while we’re still here on Earth?; Are special charisms like speaking in tongues for our time or are they ended and dangerous to seek?; etc.)

I have never looked to the institutional element (or leadership) as the basis of my faith but as something my faith tells me is a necessary but limited aspect of the Church on Earth subject to human foible and error (apart from essential teachings derived from Apostolic Tradition).

Father Michael, the word “trinity” isn’t mentioned in Scripture, either, yet the idea of God as Trinity is fundamental to any understanding of Christianity. As far as “sola scriptura” goes, I recommend 2 Timothy 3: 14-17.

But as for you, continue in what you have learned and have become convinced of, because you know those from whom you learned it, and how from infancy you have known the holy Scriptures, which are able to make you wise for salvation through faith in Christ Jesus. All Scripture is God-breathed and is useful for teaching, rebuking, correcting and training in righteousness, so that the man of God may be thoroughly equipped for every good work.

Now, since the New Testament had not yet been canonized, St. Paul obviously was referring to the Old Testament — which contains the divine demand for murderers to be exectuted (Gen. 9:5-6), a demand the Catholic Church willfully ignores to promote its own abolitionist stance.

If Catholicism is willing to abandon that command, what other moral demands in Scripture has it abandoned that it did not find suitable?

John, you should seriously consider that.

John, have you heard of the sports phrase, “You are what your record says you are”? It means that regardless of innate talent, potential or other people’s opinions, what you do on the field shows who you really are.

Too many Catholics have been blase about, or resigned to, their “leadership’s” failures. Show me the behavior of Catholic “leadership” throughout the centuries and tell me why I shouldn’t consider that leadership apostate? Because what the “leaders” preach, the laity inevitably will follow (despite birth control).

You claim that Christ founded the Catholic Church. Well, in the 1880s, Pope Leo XIII had this terrifying vision of Satan talking to Jesus:

Satan: I can destroy the Catholic Church

Jesus: You can? Then go ahead.

Satan: I need time and I need power.

Jesus: How much time and how much power?

Satan: I need a century and the power to control those who will give themselves over to me.

Jesus: You have the time. You have the power. Do what you want.

Because of that vision, Pope Leo composed the Prayer to St. Michael the Archangel. The whole scenario begs two questions:

1. If archangels are loyal subordinates of the Triune God, and one Person of that Triune God gives Satan permisssion to do anything, is an archangel seriously going to countermand that permission?

2. If those who “belong to Jesus” (for lack of a better phrase) according to John 10: 28-29….

I give them eternal life, and they shall never perish; no one can snatch them out of my hand. My Father, who has given them to me, is greater than all; no one can snatch them out of my Father’s hand.

…then why would Jesus give Satan permission to destroy the Catholic Church, especially if Jesus founded it and said He would protect it?

Either Jesus is lying or the Catholic Church is an apostate imitation of what He intended. No other conclusion is tenable.

At the beginning of Christianity there were no denominations: No Catholic, Orthodox or Protestant. Only one Baptist! 🙂

One Pope has a vision, and I’m supposed to take that to heart, and give up on the Church? Seriously? You are delusional. You are clutching at straws to justify your scism.

Popes are infallible in the core matters of the faith, but in nothing else. Visions ain’t in it.

And, you propose one should accept Sola Scriptura because one verse says scripture is useful? Of course it is useful. No one has ever denied it. I’ve seen a verse that says that Tradition is useful. So what? Shall we propose Sola Tradition as a basis of faith? That’s just as silly.

Both old and new Testaments are redolent of the Trinity. For instance, Jesus didn’t say “In the names (plural) of the Father, Son and Holy Spirit.” And Christians from the beginning believed both that there is only one God, AND worshipped both Father and Son. It was not a big jump to defining the Trinity.

However Christians went 1500 years without the idea of Sola Scriptura. And once a modern splinter group tried to put that kooky innovation into practice, they were instantly plagued with an unstoppable epidemic of fragmentation. Their theory was self-refuting. This is not surprising, since Scripture was never intended to teach doctrine or practice. It tests them.

Joseph, this kind of proof-texting just shows why there are 30,000 Protestant denominations, each one claiming they have the plain teaching of scripture. When you set yourself up as your own pope, and start grabbing verses out of the Bible, you can prove ANYTHING.

If you want to play that game, Jesus superseded the OT law on divorce with a new one. Right? But most Protestant churches have dropped His prohibition of divorce to “go with the flow.” The Catholic Church has not.

If Protestantism is willing to abandon that command, what other moral demands in Scripture has it abandoned that it did not find suitable?

PS: If you really dig scripture, I recommend a book I’m reading, Jesus: A Theography, by Sweet and Viola.

The authors are Protestants, but I’d commend it to Catholics and Protestants alike.

Joseph, Pope Leo’s vision was a “private revelation” and thus it is necessary that it be believed or accepted. Points you raise might even argue against it’s authenticity.

Yet, Pope Leo may have “overheard” something in the spiritual realm but not entirely understood what he heard.

In any event, God allowed Satan to attack Job as he knew Job’s faith and commitment would only become stronger as a consequence of having been sorely tried.

Sorry, I meant to say that it’s NOT necessary to accept Pope Leo’s private revelation.

If even a pope departs from what has always and everywhere been taught and by everyone believed in the Church, then he can be resisted. Many Catholics agree with you Joseph about capital punisment. Though to be fair, JP II argued that he wasn’t contradicting the teaching but claiming it didn’t apply in today’s circumstances. You’re probably aware that this is one of the areas tradionalist Catholics are in dissent from the modern papacy.

Father Michael, JPII’s view on capital punishment for murder is a pivotal reason why I left the Catholic Church, which has ignored (thanks to him) the fundamental reason for it in the first place: Murder is the ultimate desecration of the divine image in humanity. Unless I’m mistaken, God has not stopped creating the human race in His image.

In light of the above principles, for any pope to assert that capital punishment doesn’t apply in today’s circumstances not only is to contradict previous teaching but to set prudential judgment above revelation. One can easily make the statement I made, given JPII’s activism on the issue.

For all intents and purposes, JPII initiated dissent from centuries of teaching on the issue. Or, as John said, when you set yourself up as your own pope, and start grabbing verses out of the Bible, you can prove ANYTHING.

John, so what if there are 30,000 Protestant denominations? I don’t hear people like you complaining about the considerably fewer number of Orthodox denominations, which are based primarily on national and ethnic differences (Greek v. Russian v. Serbian Orthodox, for example).

Besides, John, if the Catholic Church claims to be the “One True Church” that proclaims “the fullness of the Gospel,” then God views it under far, far more strenuous criteria. Remember, as Peter quoted Isaiah, judgment begins in the House of God.

I strongly suggest you read Ezekiel 34 and 1 Samuel 2:12-36. God is not amused when people abuse the authority they claim in His name — and there’s no question that Catholic prelates have abused that authority for centuries!

Regarding Tradition, you are going to have to show me (as opposed to assert blindly) where Scripture says that “tradition is useful” and how that pertains to Cath0lic traditions that did not arise until after the First Century.

Regarding Scripture, John, you state that nobody has ever denied that Scripture is useful, then you say that Scripture was never intended to teach doctrine or practice. Which is it, especially in light of Paul’s letter to Timothy, the translation of which clearly includes, “teaching”?

I don’t have much experience with Hispanic culture, so I can’t add much of value to this interesting topic, although I would encourage you to consider this from the perspective of the man acting like a man.

A man who leaves the gang and becomes a Pentecostal is still a man. He is the head of his home. He’s responsible for his life. In fact, he’s taking responsibility for his life. The gang leaders may not agree with his decision, but they can respect it.

A man who leaves the gang to be a Catholic is wimping out. (Or at least it’s easy to perceive the decision that way.) He’s given up his manhood and placed himself in the effeminate world of Catholicism.

Men admire strength. There is very little about playing church with the Catholics that invokes that idea.

Regarding Scripture, John, you state that nobody has ever denied that Scripture is useful, then you say that Scripture was never intended to teach doctrine or practice. Which is it, especially in light of Paul’s letter to Timothy, the translation of which clearly includes, “teaching”?

Joseph, there’s no contradiction. Scripture is obviously not intended to teach doctrine or practice, since it just doesn’t. Imagine you had a thousand very smart Hindus who knew nothing about Christianity. And you paid them to spend decades learning Greek and Hebrew. And then gave them the scriptures and asked them to outline Christian doctrine and practice. What would you get?

Would they be able to perform any sort of normal Christian worship service? No. Would their marriages and baptisms and burials look like anything Christian? No. Would they come up with doctrines like the Trinity or the perpetual virginity of Mary? The Real Presence? Not a chance.

These are all traditions handed down from the Apostles, or developed out of those traditions by the early Church. The Eucharist as described by St Justin in AD 155, though simpler, is clearly the same thing as our Eucharist today. But it is not described like that in scripture. You could not learn “how to do it” from the Bible. Yet it’s been handed down unchanged in its essence.

Yet scripture IS useful. Supremely so. Scriptures are divinely-inspired snapshots of Jesus and the Apostles at work. We can test the traditions that have been handed down to us by seeing if they continue to comport well with scripture. (And of course it’s useful in many other ways too.)

“I don’t hear people like you complaining about the considerably fewer number of Orthodox denominations.” That’s irrelevant, since I was writing about Sola Scriptura, which they don’t believe. In fact we do complain about that, but in a different context.

“Besides, John, if the Catholic Church claims to be the “One True Church” that proclaims “the fullness of the Gospel,” then God views it under far, far more strenuous criteria.” I’m sure He does. But that doesn’t give you an out. You are not God.

If J-P II had contradicted dogma, you might have an excuse for leaving the Church, though I doubt it. But it is the job of the successors of the Apostles to interpret the teachings for us. And those interpretations can be imperfect. They may be revised or re-thought later. Cardinal Ratzinger, as Prefect of the Faith under J-P II, specifically mentioned war and the death penalty as issues Catholics may disagree on.

UNITY is and always has been an explicit commandment of Jesus, AND a core dogma of the Church. It is not something you can trifle with because you don’t like something the Pope said.

Actually Scripture is one of the two sources of doctrine. St. Paul told Timothy to adhere to what he had received through letter AND oral instruction. Clearly the books and letters of Sacred Scripture presuppose that many things are already believed and understood. Taken as a whole, the Bible does not give any ordered exposition on belief or doctrine.

As for a pattern of public worship revealed by scripture, the Old Testament presents us with one that is highly cultic and ritualized (liturgical) while the New Testament gives us one that is…highly cultic and ritualized, which is to say liturgical. The Book of Revelation gives us a glimpse of Heavenly worship, and it’s not a free form prayer meeting. People stand, bow, prostrate themselves. Elders wear and throw down crowns (the earliest headdress for bishops and still the norm in the Christian East) and all repeat various formulaic prayers over and over again (watch out for that “vain repetition”!).

John, you say that Scripture does not teach doctrine or practice. Well, how would you explain the rules for worship from Exodus to Deuteronomy, the construction of the Temple (twice), and the NT epistles…which were written to Christians, by Christians, for Christians about practicing the faith in daily circumstances, including worship (see St. Paul’s admonitions to the Corinthians about their “love feasts” in 1 Corinthians 11: 17-34.)?

Your illustration about Hindus not only is irrelevant and ignorant, but asinine. It does not take a profound theologian to recognize that both the OT and NT were designed to guide Jews and Christians, not non-Jews and non-Christians (and, yes, I know that the Jews don’t regard the NT as inspired but I’m making a broader point).

As far as JPII is concerned, he did contradict dogma regarding capital punishment (Gen. 9: 5-6). If the Church doesn’t view a direct command from God as dogma, then its spiritual and theological perception is sorely lacking, to put it diplomatically.

When it comes to divine judgment, you claim that I am not God. True. So what? Isaiah wasn’t God when he said that “judgment begins in the House of God. St. Peter wasn’t God when he quoted Isaiah. Ezekiel wasn’t God when he devoted an entire chapter (34) to the corrupt, narcissistic “false shepherds” of his day. Does one have to be divine or prophetic to see what’s right in front of one’s face, let alone cite Scripture…which conveys the very essence of God’s character and integrity?

Finally, regarding the number of Protestant denominations. Again, so what? You effectively argue that the Catholic Church has to be the “One True Church” because of its lack of “schism.” Well, there are a lot of schisms in the church: traditionalist v. progressive, “Spirit of Vatican II” types v. TLM types, etc. You think these parties agree on very much? They’ve effectively given anathemas to each other. Just read some the Catholic blogs around.

Besides, if the Catholic Church has sold its spiritual patrimony for power, prestige, wealth, monarchist trappings, secular influence and institutional arrogance, then what difference does it make how many Protestant denominations exist? The “One True Church” should focus on its own institutional repentance; anything else is misdirection.

Father Michael, I’m sure you know that Timothy’s mother was Jewish, so any “oral instructions” would have had to have been made in a Jewish context. Besides, St. Paul doesn’t specify what those instructions were. Moreover, St. Paul effectively declares Scripture (which he viewed as the NT) to be the lens through which Timothy should view any “oral instructions.” Otherwise, why would he bother to declare that “all of Scripture is divinely inspired and, therefore, useful for teaching … and training in righteousness”?

Regarding worship, Jesus had a reasons for warning against “vain repetition.” Apparently, the religious authorities of His day relied on formulaic responses to God. As a result, they didn’t have to look within themselves, confront their faults or sins, or express themselves honestly to God. They could hide behind formulas. In public, they could use those formulas to ingratiate themselves to the devout.

“Vain repetition” isn’t just a Catholic problem. It’s a problem throughout all branches of Christianity. Each branch might have a different way of expressing it, but the fundamental problem is the same.

How does God want to be worshipped, Father Michael? In spirit and truth. What does that mean? I think it means that our very lives must be acts of worship. I think that’s what St. Paul meant when he wrote the Roman Christians to “present your bodies as a living sacrifice.”

Regarding worship in the Book of Revelation, how do you know that it was “highly cultic and ritualized”? We’re talking about people who are in the immediate physical presence of God. One could imagine that being in God’s presence like that would generate spontaneous responses. The simple fact is that we really can’t know, one way or the other, until we experience that ecstasy.

Joseph, in every single paragraph here you mis-represent something I’ve written. For instance I twice wrote clearly that my argument about the number of Protestant denominations was about Sola Scriptura. Nothing else.

You twist my point that scripture does not teach us “how to do” a Christian worship service into claiming that I don’t think scripture mentions worship. Paul mentions love feasts, but he doesn’t lay out how to actually perform one.

My point that that the hypothetical Hindus could not discover “how to do” Christian practice you twist into claiming I wrote that scripture is meant to guide non-Christians.

These are just too many distortions to attribute to accident. You are being intellectually dishonest. So I will not continue this discussion.

John, you are the one who made a big deal about the number of Protestant denominations, which you claim to be the result of sola scriptura. My point still stands: What difference does it make how many Protestant denominations interpret Scripture if the one church that supposedly is entrusted with it ignores a fundamental moral point (Gen. 9; 5-6)?

I never claimed you wrote that Scripture was meant to guide non-Christians. I said that your hypothetical example was ridiculous. If you don’t like having your examples criticized, then don’t use them.

You claim that I misrepresent your views on Scripture. John, at the end of Post 19, you said the following:

“Scripture was never intended to teach doctrine or practice. It tests them.”

I didn’t put those words in your mouth. What is somebody supposed to think when one reads something like that?

You seem to be a graduate from the Mark Shea Correspondence School Of Rhetoric. When confronted with the questions and logical assumptions resulting from your positions, you claim victimization and point at your interlocutor’s supposed lack of character. He does the same thing; you just do it far less obnoxiously.

Personally, whether you worship as a Catholic is your business. I’m not trying to convert you out of Catholicism. But neither you nor Pope Francis can entice me back into a church that, despite its claims, behaves as if it never made those claims to begin with.

One final point:

If Christianity were a matter of joining the “right” church, then it would have no more moral or spiritual impact than joining the right country club.

One correction in Post 29: St. Paul viewed the OT as divinely inspired, since the NT had not yet been fully compiled.