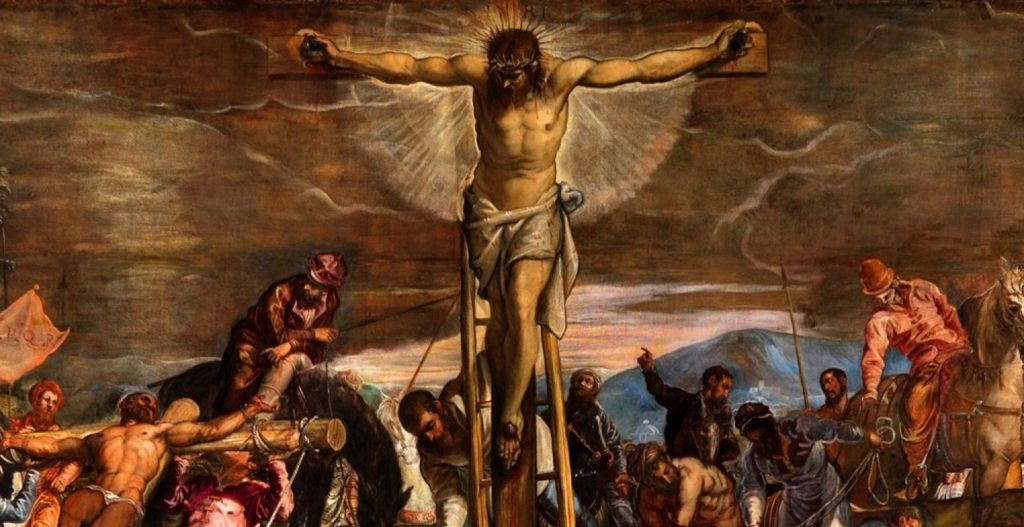

When I am lifted up from the earth, I will draw all men to myself

Mount Calvary Church

Eutaw Street and Madison Avenue

Baltimore, Maryland

A Parish of the Roman Catholic Personal Ordinariate of St. Peter

Anglican Use

Rev. Albert Scharbach, Pastor

Lent V

March 18, 2018

8:00 AM Said Mass

10:00 AM Sung Mass

The Great Litany

Hymns

What wondrous love

O sacred head, sore wounded (PASSION CHORALE)

Anthems

Lord we beseech Thee, Adrien Batten

Peccantem me quotidie, Cristóbal de Morales

___________________________________________

The Great Litany

Hymns

What wondrous love

What wondrous love is, as its repetitions evidence, an American folk hymn, from the Second Great Awakening. This hymn articulates the question that Christians ask every day: what did I do to deserve such a wonderful love from God and from Christ? The hymn is an offering of thanks to the Son for laying aside his crown as King and humbling himself even unto death. Jesus took on the sin and shame of man and thereby became the Lamb who was slain to save us from our sins. Jesus is not only the Lamb, but he is I AM, Lord and God. Our response is endless praise, and forever we shall marvel and ask, “What wondrous Love?”

What wondrous love is this, O my soul, O my soul!

What wondrous love is this, O my soul!

What wondrous love is this that caused the Lord of bliss

to bear the dreadful curse for my soul, for my soul,

to bear the dreadful curse for my soul?When I was sinking down, sinking down, sinking down,

when I was sinking down, sinking down;

when I was sinking down beneath God’s righteous frown,

Christ laid aside his crown for my soul, for my soul,

Christ laid aside his crown for my soul.To God and to the Lamb, I will sing, I will sing,

to God and to the Lamb, I will sing;

to God and to the Lamb who is the great I AM –

while millions join the theme, I will sing, I will sing;

while millions join the theme, I will sing.And when from death I’m free, I’ll sing on, I’ll sing on,

and when from death I’m free, I’ll sing on;

and when from death I’m free, I’ll sing and joyful be,

and through eternity, I’ll sing on, I’ll sing on,

and through eternity I’ll sing on.

As a folk hymn the exact history of What wondrous love is not entirely clear. It is sometimes described as a “white spiritual” from the American South.

The hymn’s lyrics were first published in Lynchburg, Virginia in the c. 1811 camp meeting songbook A General Selection of the Newest and Most Admired Hymns and Spiritual Songs Now in Use. The lyrics may also have been printed, in a slightly different form, in the 1811 book Hymns and Spiritual Songs, Original and Selected, published in Lexington, Kentucky. (It was included in the third edition of this text published in 1818, but all copies of the first edition have been lost.) In most early printings, the hymn’s text was attributed to an anonymous author, though the 1848 hymnal The Hesperian Harp attributes the text to a Methodist pastor from Oxford, Georgia, named Alexander Means.

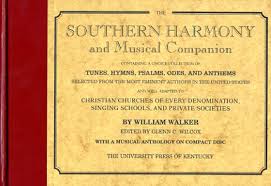

The tune was discovered by composer William Walker on his journey through the Appalachian region of America. Though the tune had been around for many years, it was passed on by rote, and not written down. Walker decided in 1835 that he would change that, and added the hymn to his collection Southern Harmony. The Appalachian region is well known for having many Irish and Scottish immigrants, which is shown in the hymns haunting text and minor tune. The hymn is written in a way that made it easy to pass on from generation to generation, repetition of lyrics. The hymn was written in the early 1800’s, a time when hymnals were scarce and music was rarely written down. To make it easier for people to learn hymns (Especially in the time of the Second Great Awakening), the author would often times write the same lyrics over and over again to drive home the point, while still keeping the text simple and easy to learn.

The hymn is sung in Dorian mode, giving it a haunting quality. Though The Southern Harmony and many later hymnals incorrectly notated the song in Aeolian mode (natural minor), even congregations singing from these hymnals generally sang in Dorian mode by spontaneously raising the sixth note a half step wherever it appeared. Twentieth-century hymnals generally present the hymn in Dorian mode, or sometimes in Aeolian mode but with a raised sixth. The hymn has an unusual meter of 6-6-6-3-6-6-6-6-6-3. The meter of “What Wondrous Love” derives from an old English ballad about the infamous pirate Captain Kidd:

My name was Robert Kidd, when I sailed, when I sailed;

My name was Robert Kidd, when I sailed;

My name was Robert Kidd, God’s laws I did forbid,

So wickedly I did when I sailed, when I sailed

So wickedly I did when I sailed.

(His real name was William; Americans erroneously called him Robert.)

A popular style of singing during this time was Shape Note Singing, which is a form of singing that uses shapes to denote which pitch should be sung, instead of the traditional European notation that we find in most music now-a-days. In order for the shape note singing to be done correctly, the congregation would be divided into four different sections, and each section was given a different part to sing. This was easier for people to sing, because most people during that time had no idea how to read music, and Shape Note Singing was a way to take something like music and give it to everyone, even the unlearned. The repetitious lyrics also made the text easy to remember.

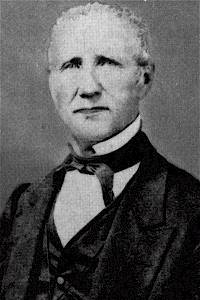

William Walker (1809-1875)

William Walker was born in Martin Mills, South Carolina in 1807 and grew up just outside of Spartanburg, where, in order to distinguish the difference between himself and other William Walkers, he was nicknamed “Singing Billy.” In 1835 he published a collection of four-shape Shape Note tune books entitled Southern Harmony. This was used for many years and was revised several different times, the final of which was printed in 1854 and is still used today in Kentucky at several different camp meetings. In 1846 Walker published another tune book that was supposed to be used as an index to Southern Harmony. The Publication was entitled The Southern and Western Pocket Harmonist, which contained several different camp meeting tunes. in 1867 Walker published another tune book entitled Christian Harmony where he adopted a new shape notation that contained seven different shapes instead of the traditional four shapes. Christian Harmony shared many similarities with Southern Harmony, but the biggest difference of note was the addition of the Alto harmony in tunes that previously did not contain that particular harmony. William Walker lived a long life, and finally passed away in Spartanburg, South Carolina in 1875. He has an influence that continues still today with the singing of traditional Shape Note tunes at conventions around the country and especially groups such as the Sacred Harp Singers of Georgia and Alabama.

In 1952, American composer and musicologist Charles F. Bryan included What Wondrous Love Is This in his folk opera Singin’ Billy, loosely based on Walker’s life as a singing school teacher. In 1958, American composer Samuel Barber composed Wondrous Love: Variations on a Shape Note Hymn (Op. 34), a work for organ, for Christ Episcopal Church in Grosse Pointe, Michigan; the church’s organist, an associate of Barber’s, had requested a piece for the dedication ceremony of the church’s new organ. The piece begins with a statement that closely follows the traditional hymn; four variations follow, of which the last is the “longest and most expressive.” Here is a performance. In 1966, the United Methodist Book of Hymns became the first standard hymnal to incorporate What Wondrous Love.

Here is the St. Olaf choir singing What Wondrous Love. Here is a shape note choir singing the hymn at Berea College. The Germans have taken up shape note singing. Here is a chamber setting for piano and viola and variations for solo violin.

________________________________________

O sacred head, sore wounded (PASSION CHORALE)

O sacred head sore wounded was composed by Paul Gerhardt (1607—1676), who closely modeled it after a stanza of a poem, Salve mundi salutare, possibly by St. Bernard of Clairvaux (1091-1153) or Arnulf of Leuwen, which contains seven stanzas meditating on how the different parts of Jesus’ body suffered during the Passion. The head is the seat of honor, “face,” and was insulted by a mocking crown of thorns, by spit, and blows from fists. Yet it is the vision of that face that will be our happiness and joy forever, for He has born all our guilt and shame, and given us His life.

O sacred head, sore wounded,

Defiled and put to scorn;

O kingly head, surrounded

With mocking crown of thorn:

What sorrow mars Thy grandeur?

Can death Thy bloom deflow’r?

O countenance whose splendor

The hosts of heav’en adore!2 Thy beauty, long desired,

Hath vanished from our sight;

Thy pow’r is all expired,

And quenched the light of light.

Ah me! for whom Thou diest,

Hide not so far Thy grace:

Show me, O Love most highest,

The brightness of Thy face.3 In Thy most bitter passion

My heart to share doth cry,

With Thee for my salvation

Upon the cross to die.

Ah, keep my heart thus moved

To stand Thy cross beneath,

To mourn Thee, well-beloved,

Yet thank Thee for Thy death.4 What language shall I borrow

To thank Thee, dearest friend,

For this Thy dying sorrow,

Thy pity without end?

Oh, make me Thine for ever!

And should I fainting be,

Lord, let me never, never

Outlive my love for Thee.5 My days are few, O fail not,

With Thine immortal pow’r,

To hold me that I quail not

In death’s most fearful hour;

That I may fight befriended,

And see in my last strife

To me Thine arms extended

Upon the cross of life.

Here is the King’s College choir.

The Latin text on which the hymn is based is:

Salve mundi salutare, Ad faciem:

Salve, caput cruentatum,

totum spinis coronatum,

conquassatum, vulneratum,

arundine verberatum,

facie sputis illita.

salve, cujus dulcis vultus,

immutatus et incultus,

immutavit suum florem,

totus versus in pallorem

quem […] coeli curia.

Omnis vigor atque viror

hinc recessit, non admiror,

mors apparet in aspectu

totus pendens in defectu,

attritus aegra macie.

sic affectus, sic despectus,

propter me sic interfectus,

peccatori tam indigno

cum amoris intersigno

appare clara facie.

In hac tua passione,

me agnosce, pastor bone,

cujus sumpsi mel ex ore,

haustum lactis cum dulcore,

prae omnibus deliciis.

non me reum asperneris,

nec indignum dedigneris,

morte tibi jam vicina,

tuum caput hic inclina,

in meis pausa brachiis.

Tuae sanctae passioni

me gauderem interponi,

in hac cruce tecum mori:

praesta crucis amatori,

sub cruce tua moriar.

morti tuae tam amarae

grates ago, Jesu chare;

qui es clemens, pie Deus,

fac quod petit tuus reus,

ut absque te non finiar.

Dum me mori est necesse,

noli mihi tunc deesse;

in tremenda mortis hora

veni, Jesu, absque mora,

tuere me et libera.

cum me jubes emigrare,

Jesu chare, tunc appare:

o amator amplectende,

temetipsum tunc ostende

in cruce salutifera.

Here is a translation of the Latin:

I Hail, bleeding Head of Jesus, hail to Thee! Thou thorn-crowned Head, I humbly worship Thee! O wounded Head, I lift my hands to Thee; O lovely Face besmeared, I gaze on Thee; O bruised and livid Face, look down on me!

II Hail, beauteous Face of Jesus, bent on me, Whom angel choirs adore exultantly! Hail, sweetest Face of Jesus, bruised for me– Hail, Holy One, whose glorious Face for me Is shorn of beauty on that fatal Tree!

III All strength, all freshness, is gone forth from Thee: What wonder! Hath not God afflicted Thee, And is not death himself approaching Thee? O Love! But death hath laid his touch on Thee, And faint and broken features turn to me.

IV O have they thus maltreated Thee, my own? O have they Thy sweet Face despised, my own? And all for my unworthy sake, my own! O in Thy beauty turn to me, my own; O turn one look of love on me, my own!

V In this Thy Passion, Lord, remember me; In this Thy pain, O Love, acknowledge me; The honey of whose lips was shed on me, The milk of whose delights hath strengthened me Whose sweetness is beyond delight for me!

VI Despise me not, O Love; I long for Thee; Contemn me not, unworthy though I be; But now that death is fast approaching Thee, Incline Thy Head, my Love, my Love, to me, To these poor arms, and let it rest on me!

VII The holy Passion I would share with Thee, And in Thy dying love rejoice with Thee; Content if by this Cross I die with Thee; Content, Thou knowest, Lord, how willingly Where I have lived to die for love of Thee.

VIII For this Thy bitter death all thanks to Thee, Dear Jesus, and Thy wondrous love for me! O gracious God, so merciful to me, Do as Thy guilty one entreateth Thee, And at the end let me be found with Thee!

IX When from this life, O Love, Thou callest me, Then, Jesus, be not wanting unto me, But in the dreadful hour of agony, O hasten, Lord, and be Thou nigh to me, Defend, protect, and O deliver me.

X When Thou, O God, shalt bid my soul be free, Then, dearest Jesus, show Thyself to me! O condescend to show Thyself to me,– Upon Thy saving Cross, dear Lord, to me,– And let me die, my Lord, embracing Thee!

Membra Jesu Nostri, The Limbs of Our Jesus, (BuxVW 75), is a cycle of seven cantatas composed by Dieterich Buxtehude in 1680. This work is the first Lutheran oratorio. The main text is from Salve mundi salutare – also known as the Rhythmica oratio . It is divided into seven parts, each addressed to a different part of Christ’s crucified body: feet, knees, hands, sides, breast, heart, and head (ad faciem)

Arnulf of Leuven (c. 1200–1250) was the abbot of the Cistercian in Villers-la-Ville. After serving in this office for ten years, he abdicated, hoping to pursue a life devoted to study and asceticism. He is now consider the probable author of Salve mundi salutare.

PASSION CHORALE: The music for the German and English versions of the hymn is by Hans Leo Hassler, written around 1600 for a secular love song, “Mein G’müt ist mir verwirret” (My heart is distracted by a gentle maid), which first appeared in print in the 1601 Lustgarten neuer teutscher Gesäng, Balletti, Galliarden und Intraden. The tune was appropriated and rhythmically simplified for Gerhardt’s German hymn in 1656 by Johann Crüger. It first appeared with the Gerhardt text in Praxis Pietatis Melica (1656). Johann Sebastian Bach arranged the melody and used five stanzas of the hymn in the St Matthew Passion. He also used the hymn’s text and melody in the second movement of the cantata Sehet, wir gehn hinauf gen Jerusalem (BWV 159). Bach used the melody on different words in his Christmas Oratorio, in the first part (no. 5). Franz Liszt included an arrangement of this hymn in the sixth station, Saint Veronica, of his Via Crucis. The Danish composer Rued Langgaard composed a set of variations for string quartet on this tune. It is also employed in the final chorus of Sinfonia Sacra, the 9th symphony of the English composer Edmund Rubbra. Peter Paul and Mary used the tune in their Because all men are brothers and Paul Simon used it in American Tune.

________________________________________

Anthems

Lord we beseech Thee, Adrian Batten

Lord, we beseech thee, give ear unto our prayers, and by thy gracious visitation lighten the darkness of our hearts, by our Lord Jesus Christ. Amen.

Here is a performance in Orem, Utah.

Adrian Batten (c. 1591 – c. 1637) was an English organist and Anglican church composer. He was the choirmaster at Westminster Abbey and St. Paul’s Cathedral. He was active during an important period of English church music, between the Reformation and the Civil War in the 1640s. During this period the liturgical music of the first generations of Anglicans began to diverge significantly from music on the continent. Batten developed the simple and direct style pioneered by Tallis during the reign of Edward VI in the late 1540s. The piece begins in a minor key with a plea to Gd to give ear unto our prayers, It changes to the relative major key at “and may thy gracious visitation lighten the darkness of our hearts.”

______________________________________

Peccantem me quotidie, Cristóbal de Morales

Peccantem me quotidie et non penitentem, Timor mortis conturbat me. Quia in inferno nulla est redemptio. Miserere mei, Deus, et salva me.

I who sin every day and am not penitent, the fear of death troubles me. For in hell there is no redemption. Have mercy upon me, O God, and save me.

This is a responsory of the Office of the Dead, in the third Nocturn of Matins. The phrase Timor mortis conturbat me was frequently used as a recurring line in medieval English poetry. This anthem uses one the most emotionally charged devices in Renaissance Polyphony: the suspension. The voices more quickly together on “conturbat me,” on “peccantem,” and in similarly charged words. There is an interesting contrast between “miserere mei” and “et salva me” – “have mecy on me and save me,” in which the former is set homophonically and the latter polyphonically with more motion. The piece closes with a Picardy third, a major chord as ray of hope at the close of this troubling anthem.

Here it is at Yale University’s Norfolk Chamber Music Festival.

Cristóbal de Morales

Cristóbal de Morales (c. 1500-1553) was born in Seville and, after an exceptional early education there, which included a rigorous training in the classics as well as musical study with some of the foremost composers, he held posts at Ávila and Plasencia. Earlier Spanish popes of the Borgia family held a long tradition of employing Spanish singers in the papal chapel’s choir. This had a significant effect on Morales’ success. Morales is documented three times in Rome as ‘presbyter toletanus’ in 1534. By 1535 he had moved to Rome, where he was a singer in the papal choir, evidently due to the interest of Pope Paul III who was partial to Spanish singers. He remained in Rome until 1545, in the employ of the Vatican; then, after a period of unsuccessfully seeking other employment in Italy he returned to Spain, where he held a succession of posts, many of which were marred by financial or political difficulties. While he was renowned by this time as one of the greatest composers in Europe, he seems to have been unpopular as an employee, for he began to have difficulty finding and keeping positions. Morales was the only composer of whose music the parody Mass did not constitute a majority, even though he wrote more of this type than any otherThere is some evidence that he was a difficult character, aware of his exceptional talent, but incapable of getting along with those of lesser musical abilities. He was regarded as one of the finest composers in Europe around the middle of the 16th century.

Stylistically, his music has much in common with other middle Renaissance work of the Iberian peninsula, for example a preference for harmony heard as functional by the modern ear (root motions of fourths or fifths being somewhat more common than in, for example, Gombert or Palestrina), and a free use of harmonic cross-relations rather like one hears in English music of the time, for example in Thomas Tallis. Some unique characteristics of his style include the rhythmic freedom, such as his use of occasional three-against-four polyrhythms, and cross-rhythms where a voice sings in a rhythm following the text but ignoring the meter prevailing in other voices. Late in life he wrote in a sober, heavily homophonic style, but all through his life he was a careful craftsman who considered the expression and understandability of the text to be the highest artistic goal.