Fighting and killing other human beings in a war does terrible things to the soldier, even if the war is a just, defensive, unavoidable war. Paul Fussell, who fought in the invasion of France from the south and was terribly wounded, tried to make that point in his books on war.

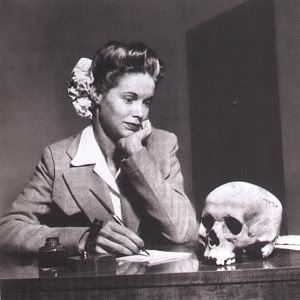

He said that in the Pacific theater soldiers used to send home Japanese skulls as souvenirs. His readers were outraged; they had lived through the war and had never heard of American soldiers doing such a thing. Fussell then produced a Life magazine cover with photograph of a young woman contemplating a Japanese skull that her boyfriend had sent to her.

Life Magazine, May 22, 1944

Wikipedia has an article on the practice:

A number of firsthand accounts, including those of American servicemen involved in or witness to the atrocities, attest to the taking of “trophies” from the corpses of Imperial Japanese troops in the Pacific Theater during World War II. Historians have attributed the phenomenon to a campaign of dehumanization of the Japanese in the U.S. media, to various racist tropes latent in American society, to the depravity of warfare under desperate circumstances, to the perceived inhuman cruelty of Imperial Japanese forces, lust for revenge, or any combination of those factors. The taking of so-called “trophies” was widespread enough that, by September 1942, the Commander in Chief of the Pacific Fleet ordered that “No part of the enemy’s body may be used as a souvenir”, and any American servicemen violating that principle would face “stern disciplinary action”.[6]

Trophy skulls are the most notorious of the so-called “souvenirs”. Teeth, ears and other such body parts were occasionally modified, for example by writing on them or fashioning them into utilities or other artifacts.[7]

Eugene Sledge relates a few instances of fellow Marines extracting gold teeth from the Japanese, including one from an enemy soldier who was still alive.

But the Japanese wasn’t dead. He had been wounded severely in the back and couldn’t move his arms; otherwise he would have resisted to his last breath. The Japanese’s mouth glowed with huge gold-crowned teeth, and his captor wanted them. He put the point of his kabar on the base of a tooth and hit the handle with the palm of his hand. Because the Japanese was kicking his feet and thrashing about, the knife point glanced off the tooth and sank deeply into the victim’s mouth. The Marine cursed him and with a slash cut his cheeks open to each ear. He put his foot on the sufferer’s lower jaw and tried again. Blood poured out of the soldier’s mouth. He made a gurgling noise and thrashed wildly. I shouted, “Put the man out of his misery.” All I got for an answer was a cussing out. Another Marine ran up, put a bullet in the enemy soldier’s brain, and ended his agony. The scavenger grumbled and continued extracting his prizes undisturbed.[8]

US Marine veteran Donald Fall attributed the mutilation of enemy corpses to hatred and desire for vengeance:

On the second day of Guadalcanal we captured a big Jap bivouac with all kinds of beer and supplies… But they also found a lot of pictures of Marines that had been cut up and mutilatedon Wake Island. The next thing you know there are Marines walking around with Jap ears stuck on their belts with safety pins. They issued an order reminding Marines that mutilation was a court-martial offense… You get into a nasty frame of mind in combat. You see what’s been done to you. You’d find a dead Marine that the Japs had booby-trapped. We found dead Japs that were booby-trapped. And they mutilated the dead. We began to get down to their level.[9]

Another example of mutilation was related by Ore Marion, a US Marine who suggested,

We learned about savagery from the Japanese… But those sixteen-to-nineteen-year old kids we had on the Canal were fast learners… At daybreak, a couple of our kids, bearded, dirty, skinny from hunger, slightly wounded by bayonets, clothes worn and torn, wack off three Jap heads and jam them on poles facing the ‘Jap side’ of the river… The colonel sees Jap heads on the poles and says, ‘Jesus men, what are you doing? You’re acting like animals.’ A dirty, stinking young kid says, ‘That’s right Colonel, we are animals. We live like animals, we eat and are treated like animals–what the fuck do you expect?’[9]

On February 1, 1943, Life magazine published a photograph taken by Ralph Morse during the Guadalcanal campaign showing a decapitated Japanese head that US marines had propped up below the gun turret of a tank. Life received letters of protest from people “in disbelief that American soldiers were capable of such brutality toward the enemy.” The editors responded that “war is unpleasant, cruel, and inhuman. And it is more dangerous to forget this than to be shocked by reminders.” However, the image of the decapitated head generated less than half the amount of protest letters that an image of a mistreated cat in the very same issue received.[10]

In October 1943, the U.S. High Command expressed alarm over recent newspaper articles, for example one where a soldier made a string of beads using Japanese teeth, and another about a soldier with pictures showing the steps in preparing a skull, involving cooking and scraping of the Japanese heads.[5]

In 1944 the American poet Winfield Townley Scott was working as a reporter in Rhode Island when a sailor displayed his skull trophy in the newspaper office. This led to the poem The U.S. sailor with the Japanese skull, which described one method for preparation of skulls (the head is skinned, towed in a net behind a ship to clean and polish it, and in the end scrubbed with caustic soda).[11]

The Marines who urinated on the bodies of dead Taliban, who had been trying to kill them and who had probably killed their friends and civilians, also paid the cost of war. That is another reason to avoid war, if at all possible.