The Adoration of the Golden Calf by Nicholas Poussin

John Henry Newton (1725 -1807) is best known as the author of “Amazing Grace” and of “Glorious Things of Thee Are Spoken.” He also wrote a hymn, “The Golden Calf,” which is the subject of today’s reading from Morning Prayer.

When Israel heard the fiery law,

From Sinai’s top proclaimed;

Their hearts seemed full of holy awe,

Their stubborn spirits tamed.Yet, as forgetting all they knew,

Ere forty days were past;

With blazing Sinai still in view,

A molten calf they cast.Yea, Aaron, God’s anointed priest,

Who on the mount had been

He durst prepare the idol-beast,

And lead them on to sin.Lord, what is man! and what are we,

To recompense Thee thus!

In their offence our own we see,

Their story points at us.From Sinai we have heard Thee speak,

And from mount Calv’ry too;

And yet to idols oft we seek,

While Thou art in our view.Some golden calf, or golden dream,

Some fancied creature-good,

Presumes to share the heart with Him,

Who bought the whole with blood.Lord, save us from our golden calves,

Our sin with grief we own;

We would no more be Thine by halves,

But live to Thee alone.

Newton was an English sailor. In 1743, while going to visit friends, Newton was captured and pressed into the naval service by the Royal Navy. He became a midshipman aboard HMS Harwich. At one point Newton tried to desert and was punished in front of the crew of 350. Stripped to the waist and tied to the grating, he received a flogging of eight dozen lashes and was reduced to the rank of a common seaman. Following that disgrace and humiliation, Newton initially contemplated murdering the captain and committing suicide by throwing himself overboard. He recovered, both physically and mentally.

Later, while Harwich was en route to India, he transferred to Pegasus, a slave ship bound for West Africa. The ship carried goods to Africa and traded them for slaves to be shipped to the colonies in the Caribbean and North America. Newton did not get along with the crew of Pegasus. They left him in West Africa with Amos Clowe, a slave dealer. Clowe took Newton to the coast and gave him to his wife, Princess Peye, an African duchess. She abused and mistreated Newton equally to her other slaves. Newton later recounted this period as the time he was “once an infidel and libertine, a servant of slaves in West Africa.”

In 1748, he was rescued by a sea captain and returned to England. During a storm, when it was thought the ship might sink, he prayed for deliverance. This experience began his conversion to evangelical Christianity. Later, whilst aboard a slave vessel bound for the West Indies, he became ill with a violent fever and asked for God’s mercy; an experience he claimed was the turning point in his life.

Despite this, he continued to participate in the Slave Trade. In 1750, he made a further voyage as master of the slave ship ‘Duke of Argyle’ and two voyages on the ‘African’. He admitted that he was a ruthless businessman and a unfeeling observer of the Africans he traded. Slave revolts on board ship were frequent. Newton mounted guns and muskets on the desk aimed at the slaves’ quarters. Slaves were lashed and put in thumbscrews to keep them quiet.

In 1754, after a serious illness, he gave up seafaring altogether. In 1757, he applied for the Anglican priesthood. It was seven years before he was accepted. In 1764, he finally became a priest at Olney in Buckinghamshire. He became well known for his pastoral care and respected by both Anglicans and nonconformists.

John Newton

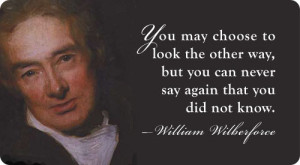

Newton began to deeply regret his involvement in the slave trade. After he became Rector of St Mary Woolnoth, in London in 1779, his advice was sought by many influential figures in Georgian society, among them the young M.P., William Wilberforce. Wilberforce was contemplating leaving politics for the ministry. Newton encouraged him to stay in Parliament and “serve God where he was”. Wilberforce took his advice, and spent the rest of his life working towards the abolition of slavery.

Worldly interests supported slavery. Evangelical Anglicans such as Newton, Hannah More, and most of all William Wilberforce were tireless advocates for ending slavery. Although derided by those who profited from slavery, the decades-long effort of these Anglicans led to the abolition of slavery in the British Empire and the use of the British navy to suppress slave trading throughout the world.