Lawrence Gilman and the World of Music

Arthur Lawrence Gilman (1878-1939) always used the name Lawrence Gilman. (See his father’s entry for a possible explanation of his omission of Arthur.) He was the son of Arthur Coit Gilman (1855-1890) and Bessie Amelia Lawrence (1858-1937). He was therefore the second cousin, three times removed, of my wife.

He was a painter and taught himself music theory and composition, piano, and organ. He set three of W. B. Yeats’ poems for voice and piano: “A Dream of Death,” The Heart of a Woman,” and “The Curlew.” He also wrote an unpublished opera in the style of Wagner.

The very young Lawrence Gilman

He was most active American music critics of the first part of the twentieth century. He was the music critic of the New York Herald-Tribune, and of Harper’s Weekly, the annotator of orchestral programs for the New York Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra and the Philadelphia Orchestra, and the radio commentator for broadcasts of New York Philharmonic concerts. His comments are still quoted in contemporary program notes.

A contemporary remembered Lawrence:

Lawrence Gilman of the Herald Tribune was a…suave, sensitive and rather morose individual of extremely aesthetic appearance who wore a fur-collared overcoat, worked for hours over each carefully turned paragraph, and produced a type of elegantly tortured prose that many New York concertgoers regarded as literature. Gilman shut out the coarse sounds of the nonmusical world by wearing plugs of cotton in his ears, except when he was on the job. At concerts, he would remove his overcoat, sit, remove his earplugs, and listen with polite concentration. When he left the concert hall the earplugs would be back securely in place.

The young Lawrence Gilman

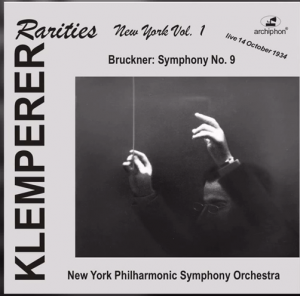

Here is a video with Lawrence’s voice in 1934 introducing Otto Klemperer conducting Bruckner’s Symphony No. 9.

Books

Lawrence wrote prolifically: Phases of Modern Music (1904), The Music of Tomorrow (1906), Stories of Symphonic Music (1907), A Guide to Strauss’ Salome (1907), A Guide to Debussy’s Pelleas et Melisande (1907), Edward MacDowell: A Study (1909), Aspects of Modern Opera (1908), Nature in Music (1914), A Christmas Meditation (1916), Music and the Cultivated Man (1929), Wagner’s Operas (1937), and Toscanini and Great Music (1938).

Invective

Lawrence had a sharp tongue.

He, like his parents, was a Wagnerian:

Since that day when, a quarter of a century ago, Richard Wagner ceased to be a dynamic figure in the life of the world, the history of operatic art has been, save for a few conspicuous exceptions, a barren and unprofitable page.

He did not like bel canto:

A plain-spoken and not too reverent observer of contemporary musical manners, discussing the melodic style of the Young Italian opera-makers, has observed that it is fortunate in that it “gives the singers opportunity to pour out their voices in that lavish volume and intensity which provoke applause as infallibly as horseradish provokes tears.”

Webern was not to his liking:

Webern’s Five Pieces were as clearly significant and symptomatic as a toothache…Men of our generation…aim, in such extreme cases as Webern, at a pursuit of the infinitesimal, which may strike the unsympathetic as a tonal glorification of the amoeba…There is undeniably a touch of the protozoic…scarcely perceptible tonal wraiths, mere wisps and shreds of sound, fugitive astral vapors…though one or twice there are briefly vehement outbursts, as of a gnat enraged..the Lilliputian Fourth Piece is typical of the set. It opens with an atonal solo for the mandolin; the trumpet speaks as briefly and atonally; the trombone drops a tearful minor ninth (the amoeba weeps)….

Stravinsky pleased Lawrence not:

The History of a Soldier is tenth-rate Stravinsky. It is probably the nearest that any composer of consequence has ever come to achieving almost complete infantilism … Regarded as a sort of musical comic strip, it is abysmally inferior, in wit, comedic power, and salience of characterization, to Mr. Herriman’s “Krazy Kat,”for instance.

He did not like Gershwin, who did not follow Wagner’s dictates about music drama:

Perhaps it is needlessly Draconian to begrudge Mr. Gershwin the song hits which he has scattered through his score [Porgy and Bess] and which will undoubtedly enhance his fame and popularity. Yet they jar it. They are its cardinal weakness. They are the blemish upon its musical integrity. Listening to such sure-fire rubbish as the duet between Porgy and Bess, “You is my woman now,”…you wonder how the composer could stoop to such easy and needless conquests.

He didn’t like Gershwin’s orchestral music either:

How trite and feeble and conventional the tunes are [in the Rhapsody in Blue]; how sentimental and vapid the harmonic treatment, under its guise of fussy and futile counterpoint!…Weep over the lifelessness of the melody and harmony, so derivative, so stale, so inexpressive!

Massenet was a mess:

There have been brave men in France; but of them all, surely the bravest was the late Jules Emile Frederic Massenet. This intrepid composer, gifted with the spiritual distinction of a butler, the compassionate understanding of a telephone girl, and the expressive capacity of an amorous tomtit, had the courage to choose as a subject for music the greatest of all tragi-comedies, the most exquisitely piteous figure in the imaginative literature of the world. Monsieur Massenet, composer of Manon and the Meditation Réligieuse, selected as the theme for an opera the Don Quixote of Cervantes, and with it he did his worst. The result of this incredible adventure was displayed to us on Saturday afternoon.

Opera in modern settings tended to bathos:

In choosing the subject for this music-drama, Puccini set himself a task to which even his extraordinary competency as a lyric-dramatist has not quite been equal. As every one knows, the story for which Puccini has here sought a lyrico-dramatic expression is that of an American naval officer who marries little “Madame Butterfly” in Japan, deserts her, and cheerfully calls upon her three years later with the “real” wife whom he has married in America. The name of this amiable gentleman is Pinkerton—B.F. Pinkerton—or, in full, Benjamin Franklin Pinkerton. Now it would scarcely seem to require elaborate argument to demonstrate that the presence in a highly emotional lyric-drama of a gentleman named Benjamin Franklin Pinkerton—a gentleman who is, moreover, the hero of the piece—is, to put it briefly, a little inharmonious. The matter is not helped by the fact that the action is of to-day, and that one bears away from the performance the recollection of Benjamin Franklin Pinkerton asking his friend, the United States consul at Nagasaki, if he will have some whiskys-and-soda. There lingers also a vaguer memory of the consul declaring, in a more or less lyrical phrase, that he “is not a student of ornithology.”

The Critic Criticized

Lawrence made a passing remark about a supposed decision of a Council that women have no souls. This provoked the ire of the Jesuits at America.

But who is Mr. Lawrence Gilman? A thousand pardons! Thumb your Who’s Who, brother, and when found, make a note on’t, that Mr. Lawrence Gilman is a gentleman with a weakness for music, a young-eyed cherub, fond of harmony,,, he has written a guide to Strauss’s Salome; he is said to be an authority on Certain Aspects of Modern Drama; and – be it spoken – he is the musical critic on the staff of the North American Review, Higher than this dizzy eminence, fame mounts but slowly; yet one gathers from the modest reticence of the Who’s Who paragraph, that Mr. Gilman likewise plays very prettily upon the organ and piano.

Seated one day at the organ, Mr. Gilman was borne on the strains of melody into new fields. He had lately read a treatise by Herr Emil Lucka, “a young Viennese philosopher whose remarkable book Eros attempts no less staggering a task than the study of the evolution of human love.” “Young” is a pat phrase, even as is “staggering” yet each is superfluous, for none but a young man would choose this topic, and even the most matured intellect would stagger under the burden. But, O woful day, on which music and metaphysics, with a dash of poetry and a hint of mysticism, met together in the heaving bosom of Mr. Lawrence Gilman! They met, but they kissed not; the fought; the dust of the battle and the shouting possessed the brain of the unhappy organist; the resulting phantasmagoria ran into Mr. Gilman’s pen to issue forth on page 910 of the North American Review: “In the beginning of the twelfth century a new and unprecedented emotion – spiritual love of man for woman based on personality – made its appearance. Woman, one despised –woman, to whom at the Council of Mâcon a soul had been denied – became now a queen, a divinity.”

This was of course nonsense. America continued

The statement then, that woman was denied a soul by the Council of Mâcon or any other Council, indicates in him who makes it, either ignorance, or a disregard of the Eighth Commandment. In Mr. Gilman it indicates ignorance, the outcome of a trusting gentle nature. His poetic mind views with amiable tolerance the hoary legends of the past; he is devoid of the critical spirit; his head is in the clouds. Very likely some suffragette, impatient of Romish conservatism, whispered this tale into his guileless ear.

And so on.

Family

Lawrence Gilman married Elizabeth Wright Walter (1875-1964) on August 1, 1904. They had one child, Elizabeth Lawrence Gilman (1905-2006). Lawrence Gilman died at Sugar Hill, in Grafton, New Hampshire September 8, 1939. The New York Philharmonic broadcast a memorial concert for him on October 22, 1939, with Siegfried’s Funeral March and the closing scene of Gotterdammerung.