The author of The Annals of Newberry was John Belton O’Neall, native of Newberry and Justice of the South Carolina Supreme Court.

John Belton O’Neall

Only in 1823 was the murder of a slave made a criminal offence in South Carolina. Before that it was punishable only by a fine. The first case heard under the new law did not occur until 1853.

O’Neall heard the appeal of Motley and Blackledge, who had been sentenced to death for the murder of a slave. Years later someone who was present in the area recounted what had happened:

While a law student verging upon manhood, in the summer of 1853, the writer made a visit from his home in Charleston to a relative in Colleton district, South Carolina. He had never seen a runaway slave. Hence, when he learned that a runaway slave bad been caught in the vicinity, he hastened to get a look at him. He soon ascertained that he was in the custody of one Robert Grant, a small farmer, who lived near a point known as “Round O,” about 15 miles from Colleton court house,

A few days after this Grant was called on by one Thomas Motley and William Blackledge, rice planters, who lived at the distance of a few miles. At their urgent request, be delivered the negro to Motley, who promised to trace out the master and have the reward paid to Grant. The negro was taken to Motley’s plantation and confined in an unused smokehouse, with a heavy ball and chain attached to his legs by strong shackles.

On the following day, as afterwards transpired, Motley and B la c k l e d g e, who were first cousins, were joined at the plantation of the former by one Derrell Rowell, a cotton planter. The negro could not have failed to observe that, on leaving the smokehouse, where they had confined him, they, with seeming carelessness, had left the door unlocked. He did not understand that they were eager for a man hunt, and required a fleeing man.

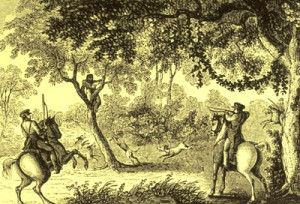

They watched the building through the night from a place of concealment until about two hours before the dawn of day, when they saw the negro come out and look cautiously around, and then pass into the darkness on his far flight for life. Three hours later, after an early breakfast, they unleashed their dogs, all trained beagles, and united them into one pack, numbering 42. The hounds were started at the door of the smoke-house, and as the trail was hot with the scent of fresh blood that trickled from the slave’s limbs, they followed it all the time with their noses in the air.

At the distance of about 10 miles from the starting point the hounds were heard to give tongue in sharp, quick barks, and the men who were following on horseback then knew well that the quarry was within clear view of the dogs and would soon be brought to bay. They rode up and found the dogs encircling a large oak and baying loudly. They soon discovered the negro hidden behind a bunch of hanging moss in the fork of a tree and they ordered him to come down. He pleaded for mercy, saying that if he came down the hounds would bite him. They assured him that he should not be hurt, and they drove the dogs back, and at the same time threatened to shoot him out of the tree if he didn’t come down at once.

The instant that his feet touched the ground they set the entire pack of hounds on him, and despite his desperate struggles they quickly bore him to the earth and his pangs were soon ended by the fierce and hungry brutes.

The murder, however, was not unseen by human eyes. A negrohunting a stray horse in the woods, heard the slave’s cry of agony as the hounds fastened their teeth in his body, and running in the direction of the sound, he witnessed the tragedy in all its horror. He also recognized the three planters, and saw and heard them urge the dogs on.

But a slave could not testify against a white person.

He hurried away from his place of concealment and reported what he had seen to his master, who at once visited the spot and observed the blood and bones and a portion of the murdered slave’s hair upon the ground, and also his footprints and the tracks made by the dogs. That man immediately sought a magistrate and repeated the statement made by his slave, and also described what he had himself seen to confirm that statement. The warrant for the arrest of the three criminals was based upon an affidavit made by a planter, setting forth the confession of Blackledge.

Blackledge confessed, hoping for immunity.

They were promptly apprehended, and, after a preliminary examination, committed to jail for trial. The trial came on at fall term. September, 1853, in the court of general sessions, at Waterboro. Judge John B. O’Neall, who was distinguished as a learned jurist, presided. The prisoners had a long array of eminent counsel. The jury, after being out 30 minutes, returned a verdict of guilty. The prisoners were sentenced to be taken to the usual public place for executions and there hanged try the neck until dead.

They appealed on various technicalities, such as whether it was proved that the victim was a slave. O’Neall rendered his decision:

Two months have passed away since you stood before me, in the midst of the community where the awful tragedy, of which you have been convicted, was performed. I hope this time has been profitable to you, and that in the midnight watchings of your solitary cells, you have turned back with shame and sorrow to the awful cruelties of which you were guilty on the 5th of July last.

Notwithstanding the enormity of your offence, you have no reason to complain that justice has been harshly administered. On the circuit and here yon have had the aid of zealous, untiring counsel — everything which man could do to turn away the sword of justice, has been done; but in vain. Guilt, such as yours, cannot escape the sanctions of even earthly tribunals.

My duty now is to pass between you and the State, and announce the law’s awful doom! Before I do so, usage and propriety demand that I should endeavor to turn your thoughts to the certain results before you. Death here, a shameful death, awaits you! I hope it may be that you may escape the terrible everlasting death of the soul.

It may be profitable to you to recall the horrid deeds, which you jointly and severally committed, in the death of the poor, begging, unoffending slave. I will not repeat the disgusting details of the outrage committed; the public are already fully informed, and your own hearts, in every pulsation, repeat them lo you. I may be permitted, however, to say to you, and to the people around you, and to the world, that hitherto South Carolina had never witnessed such atrocities: indeed, they exceed all that we are told of savage barbarity. For the Indian, the moment his captive ceases to be a true warrior (in the sense in which he understands it) and pleads for mercy, no longer extends his suffering — death, speedy death, follows. But you, for a night and part of the succeeding day, rioted in the sufferings and terrors of the poor negro, and at length your ferocious dogs, set- on by you, throttled and killed him, as they would a wild beast. Can’t you hear his awful death cry, “Oh, Lord!” If you cannot hear it, the Lord of Hosts heard and answered it. He demanded then, and now, from you, the fearful account of blood!

You have met with the fearful consequences of the infamous business in which you were engaged — hunting runaways with dogs, equally fierce and ferocious as the Spanish bloodhounds.

With one of you, (MotIey) there could have been no excuse. Your father, young man, is a man of wealth, reaped and gathered together by a life of toil and privation; that the son of such a man should, be found more than a hundred miles from home, following a pack of dogs, in the chase of negro slaves, through the swamps of the louver country, under a summers sun, shows either a love of cruelty, or of money, which is not easily satisfied. To the other prisoner, Blackledge, it may be that poverty and former devotion to this sad business, might have presented some excuses.

The Scriptures, young men, with which, I fear, you have not been familiar, declare, as the law of God, “Thou shalt not kill.” This divine statute, proclaimed to God’s own prophet, amid the lightning and thunder of Sinai, was predicated of the law, previously given to Noah, after one race of men had perished. “Whosoever sheddeth man’s blood, by man shall his blood be shed: For in the image of God made he man,” In conformity with these divine demands, , is the law of the Stale under which you have been condemned. No longer is the blood of the slave to be paid for with money; no longer is the brutal murderer of the negro to go free! “Life for life” is demanded, and you, poor, guilty creatures, have the forfeit to pay! A long experience as a lawyer and a judge makes it my duty to say to you and to the people all around you, never have I known the guilty murderer to go free! If judgment does not overtake him in the hall of justice, still the avenger of blood is in his pursuit: still the eye, which never slumbers nor sleeps, is upon him, will in some unexpected moment the command goes forth “cut him down,” and the place “which once knew him shall know him no more forever.” Since your trial, one of the witnesses, much censured for participation in some of your guilty deeds-, has been suddenly cut off from life.

I say to you young men “you must die.” Do not trust ill hopes of executive clemency. It seems to me, however much the governor’s heart may bleed to say “no” to your application, he will have to say it. Prepare yourselves, therefore, as reasonable, thinking, accountable men, for your fate. Search the Scriptures — obtain repentance by a godly sorrow for sin. Struggle night and day for pardon. Remember Christ the Saviour came to save sinners, the chief of sinners. Learn that you are such, and he will then declare to you that, “though your sins be as scarlet, they shall be white as snow, although they be red like crimson, they shall be as wool.”

The sentence of the law is, that you be taken to the place whence you last came, thence to the jail of Colleton district; that you be closely and securely confined until Friday, the third day of March next, on which day, between the hours of ten in the forenoon and two in the afternoon, you and each of you will be taken, by the Sheriff of Colleton district, to the place of public execution, and there be hanged by the neck, till your bodies be dead, and may God have mercy on your souls.

The newspaper account recount the final act:

As the day of execution approached the sheriff reported to the governor that he baa been offered a large sum of money (correctly stated to have been $ 50,000), to permit the prisoners to escape, and that he had reason to believe that an armed force was being organized for their rescue, either at the jail or the gallows. On receiving the report of the sheriff at Columbia, the capital. Gov. Manning proceeded to Charleston and ordered out the 4th brigade of state militia, the strongest and best equipped and best drilled in the state, consisting of about 5000 rank and file, and composed of infantry .cavalry and artillery. He marched across the country at the bead of the brigade, a distance of about 4o miles, to Waterloo, and stationed it at the jail.

As the condemned men had held good social position, and were in possession of wealth, with a large number of relatives active in their behalf, it is not surprising that despite their horrible crime a petition signed by many thousand persons was laid before the governor appealing to him to commute the sentence to imprisonment for life. One petition that was deemed by its signers to be special the election then pending, was signed by a majority of the legislature, then in session. The governor maintained his high resolve that justice should take its course, in accordance with the known maxim that, guided his life; “Do your duty, and leave the consequences to God;,” On the day appointed for the execution the prisoners were conducted to the scaffold by a strong military escort, the brigade forming a hollow square around it. The three murderers [actually two; Rowell may have died before the trial] were duly hanged, and so the justice and the civilization of the state vindicated.

But was it? Because he refused to grant clemency, Gov. John Lawrence Manning was defeated in the next election, 1854.

As Northerners said, the everyday cruelties of slavery, the beatings and whippings, which were almost never punished even if they ended in death, accustomed the murderers to regard slaves as not human, as mere animals to be hunted for sport.