The Baptism of the Lord

Mosaic of the Baptism showing the Jordan in the form of a classical river god and Jesus as a beardless young man

Arian Baptistry, Ravenna

Opening Hymn “I come” the great Redeemer cries. Text by Thomas Gibbons, Tune Forest Green.

“Thomas Gibbons was born at Beak, near Newmarket, May 31, 1720; educated by Dr. Taylor, at Deptford; ordained in 1742, as assistant to the Rev. Mr. Bures, at Silver Street Chapel, London; and in 1743 became minister of the Independent Church, at Haberdashers’ Hall, where he remained till his death, Feb. 22, 1785. In addition to his ministerial office he became, in 1754, tutor of the Dissenting Academy at Mile End, London; and, in 1759, Sunday evening lecturer at Monkwell Street. In 1760 the College at New Jersey, U.S., gave him the degree of M.A. and in 1764 that of Aberdeen the degree of D.D. His prose works were (1) Calvinism and Nonconformity defended, 1740; (2) Sermons on various subjects, 1762; (3) Rhetoric, 1767; (4) Female Worthies, 2 vols., 1777. T

Dr. Gibbons may be called a disciple in hymn writing of Dr. Watts, whose life he wrote. His hymns are not unlike those of the second rank of Watts. He lacked “the vision and faculty divine,” which gives life to hymns and renders them of permanent value. Hence, although several are common use in America, they are dying out of use in Great Britain.”

The gospel is the Baptism of Jesus in the Jordan.

John was reluctant to baptize Jesus, but Jesus explained that He wished “to fulfill God’s will in righteousness.” Jesus knew no sin, but he took our sins upon Himself and received John’s baptism of repentance for us, as He would receive the penalty for our sins on the cross. He became the Lamb whose sacrifice took the sins of the world away. The Father was “well-pleased” with His Son who came to take away the sins of the world, for the Father is merciful and desires not the death of the sinner, but that he repent and live.

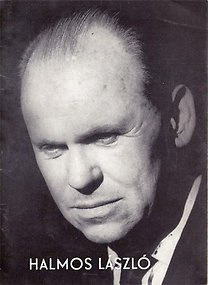

The anthem at the offertory is Iubilate Deo by László Halmos.

László Halmos (10 November 1909, in Nagyvárad – 26 January 1997, in Győr) was a Hungarian composer, choir director and violinist.

He wrote choral works, songs, chamber music, oratorios, cantatas, masses, as well as works for orchestra and for the organ, totaling several hundred works. He was choir director of Gyór Cathedral and also held the position of professor at the Theological College and the State Conservatory. As a violinist, he was one of the early members of The New Hungarian Quartet.

Here the anthem by mixed chamber choir; here at the Christ the King mass at St. Peter’s in Rome; here by a male choir at Đakova cathedral in Croatia.

The hymn at the offertory is the traditional Come, Holy Ghost.

The anthem during the communion is Georg Frederic Handel’s “Behold the Lamb of God” from the Messiah. Here is Tafelmusik’s rendition.

The closing hymn is Songs of thankfulness and praise text by Christopher Wordsworth, the nephew of the poet William Wordsworth. Hymnary gives his background, and notes the resemblance of his hymns to those of the Eastern Church:

Wordsworth, Christopher, D.D., was born at Lambeth (of which parish his father was then the rector), Oct. 30, 1807, and was the youngest son of Christopher Wordsworth, afterwards Master of Trinity College, Cambridge, and Priscilla (née Lloyd) his wife. He was educated at Winchester, where he distinguished himself both as a scholar and as an athlete. In 1826 he matriculated at Trinity College, Cambridge, where his career was an extraordinarily brilliant one. He swept off an unprecedented number of College and University prizes, and in 1830 graduated as Senior Classic in the Classical Tripos, and 14th Senior Optime in the Mathematical, won the First Chancellor’s Medal for classical studies, and was elected Fellow of Trinity. He was engaged as classical lecturer in college for some time, and in 1836 was chosen Public Orator for the University. In the same year he was elected Head Master of Harrow School, and in 1838 he married Susan Hatley Freere. During his head-mastership the numbers at Harrow fell off, but he began a great moral reform in the school, and many of his pupils regarded him with enthusiastic admiration. In 1844 he was appointed by Sir Robert Peel to a Canonry at Westminster; and in 1848-49 he was Hulsean lecturer at Cambridge. In 1850 he took the small chapter living of Stanford-in-the-Vale cum Goosey, in Berkshire, and for the next nineteen years he passed his time as an exemplary parish priest in this retired spot, with the exception of his four months’ statutable residence each year at Westminster. In 1869 he was elevated to the bishopric of Lincoln, which he held for more than fifteen years, resigning it a few months before his death, which took place on March 20th, 1885. As bearing upon his poetical character, it may be noted that he was the nephew of the poet-laureate, William Wordsworth, whom he constantly visited at Rydal up to the time of the poet’s death in 1850, and with whom he kept up a regular and lengthy correspondence.

Of his many works, however, the only one which claims notice from the hymnologist’s point of view is The Holy Year, which contains hymns, not only for every season of the Church’s year, but also for every phase of that season, as indicated in the Book of Common Prayer. Dr. Wordsworth, like the Wesleys, looked upon hymns as a valuable means of stamping permanently upon the memory the great doctrines of the Christian Church. He held it to be “the first duty of a hymn-writer to teach sound doctrine, and thus to save souls.” He thought that the materials for English Church hymns should be sought (1) in the Holy Scriptures, (2) in the writings of Christian Antiquity, and (3) in the Poetry of the Ancient Church. Hence he imposed upon himself the strictest limitations in his own compositions. He did not select a subject which seemed to him most adapted for poetical treatment, but felt himself bound to treat impartially every subject, and branch of a subject, that is brought before us in the Church’s services, whether of a poetical nature or not. The natural result is that his hymns are of very unequal merit; whether his subject inspired him with poetical thoughts or not, he was bound to deal with it; hence while some of his hymns (such as “Hark! the sound of holy voices,” &c, “See the Conqueror mounts in triumph,” &c, “O, day of rest and gladness”) are of a high order of excellence, others are prosaic. He was particularly anxious to avoid obscurity, and thus many of his hymns are simple to the verge of baldness. But this extreme simplicity was always intentional, and to those who can read between the lines there are many traces of the “ars celans artem.” It is somewhat remarkable that though in citing examples of early hymnwriters he almost always refers to those of the Western Church, his own hymns more nearly resemble those of the Eastern, as may be seen by comparing The Holy Year with Dr. Mason Neale’s Hymns of the Eastern Church translated, with Notes, &c. The reason of this perhaps half-unconscious resemblance is not far to seek. Christopher Wordsworth, like the Greek hymnwriters, drew his inspiration from Holy Scripture, and he loved, as they did, to interpret Holy Scripture mystically. He thought that ”the dangers to which the Faith of England (especially in regard to the Old Testament) was exposed, arose from the abandonment of the ancient Christian, Apostolic and Patristic system of interpretation of the Old Testament for the frigid and servile modern exegesis of the literalists, who see nothing in the Old Testament but a common history, and who read it (as St. Paul says the Jews do) ‘with a veil on their heart, which veil’ (he adds) ‘is done away in Christ.'” In the same spirit, he sought and found Christ everywhere in the New Testament. The Gospel History was only the history of what “Jesus began to do and to teach” on earth; the Acts of the Apostles and all the Epistles were the history of what he continued to do and to teach from Heaven; and the Apocalypse (perhaps his favourite book) was “the seal and colophon of all.” Naturally he presents this theory, a theory most susceptible of poetical treatment, in his hymns even more prominently than in his other writings. The Greek writers took, more or less, the same view; hence the resemblance between his hymns and those of the Eastern Church. [Rev. J. H. Overton, D.D.]

Here it is sung at St. John’s in Detroit.

Tony Esolen wrote about this hymn in Touchstone; the mutilations it has suffered from those who find the word “man” hateful and offensive are an especial object of his opprobrium:

When reciting the Nicene Creed, Roman Catholics are supposed to bow in solemn adoration when they come to the following words: Et incarnatus est de Spiritu Sancto ex Maria virgine, et homo factus est. The Incarnation is the heart of the Christian faith: a work of breathtaking love, not simply that God would make man in his image, but that he would descend to pitch his tent among us. Christ is the eternal Word of God, but his moments will be measured out by a beating heart, and his boundless wisdom will dwell within our small swaddling of flesh.

Yet this manhood, once assumed, is not discarded. It is made sublime. To quote Milton:

Therefore thy humiliation shall exalt

With thee thy manhood also to this throne:

Here shalt thou sit incarnate, here shalt reign

Both God and Man, Son both of God and man,

Anointed universal King.

If all our sins originate in, and are summed up by, the pride of Adam, so all our salvation comes from the obedience of Jesus Christ. That is why St. Paul urges us to exchange man for man: “Put off concerning the former conversation the old man . . . [and] put on the new man, which after God is created in righteousness and true holiness” (Eph. 4:22,24).

The wonder of the Incarnation is the subject of Christopher Wordsworth’s hymn for Epiphany, “Songs of Thankfulness and Praise.” Each of the stanzas ends with the euphonious line, “God in man made manifest.” Now, “man” and “manifest” are etymologically unrelated, but their similarity in English makes the line peculiarly effective. Ever since Jesus appeared in the world, God has had a human face. When the Apostle Philip, an earnest fellow though a tad slow, asked Jesus to show them the Father, our Lord replied, “Have I been so long a time with you, and yet hast thou not known me, Philip? He that hath seen me hath seen the Father” (John 14:9).

So the poem proceeds from one manifestation of Jesus to the next. We begin with the first Epiphany:

Songs of thankfulness and praise,

Jesus, Lord, to thee we raise,

Manifested by the star

To the sages from afar;

Branch of royal David’s stem

In thy birth at Bethlehem;

Anthems be to thee addrest,

God in man made manifest.

The star led the eastern sages to the home at Bethlehem, where they beheld the little boy, the Son of David. It was no earthshaking manifestation. The astronomical sign, whatever it was, seems to have escaped the notice of the Jews themselves, whom the Son of David most concerned. But we follow the sages to the lowly dwelling, and to the child who was far more than they knew.

The foolish editors of the Canadian Book of Worship III could not abide the word “man,” which of course is the focus of the whole poem, so they changed the phrase to “in flesh” in the first stanza, and to “on earth” in the second. They omitted the third stanza altogether. What they did to the fourth, I will show soon.

But the original, not emasculated, not impersonal, brings us the man Jesus, revealed—at first still in a half-secret way—as walking and speaking and celebrating among the people of his time and place, and as filled with divine power:

Manifest at Jordan’s stream,

Prophet, Priest, and King supreme;

And at Cana, wedding guest,

In thy Godhead manifest;

Manifest in power divine,

Changing water into wine;

Anthems be to thee addrest,

God in man made manifest.

From the gently luminous miracle at Cana, remarked perhaps by only a few, where Jesus, to whose wedding feast all men are called, was only one guest among the crowd, we turn to the wonders he performed on the open hillsides and in the village squares, healing the sick. That leads in turn to the greatest victory over our ills, that of the divine physician giving his life for the dead, and killing the power of the evil one:

Manifest in making whole

Palsied limb and fainting soul;

Manifest in valiant fight,

Quelling all the devil’s might;

Manifest in gracious will,

Ever bringing good from ill;

Anthems be to thee addrest,

God in man made manifest.

“Not my will but thine be done,” said Jesus in the garden. This stanza, with its insistent repetition of the word “manifest,” leads the singer to consider when our Lord was most poignantly revealed to the world. That was when he was stripped and nailed to the cross, raised up before the eyes of us sinners, naked in his loving might and in his assumption of all our infirmities.

The final stanza is a plea that the Lord will continue to manifest himself to us, both in the sacred Scripture and in our lives, when we have been blessed with the indwelling Spirit. That will bring us to the consummate epiphany. In the words of St. John, which the poet clearly has in mind: “When he shall appear, we shall be like him; for we shall see him as he is” (1 John 3:2).

The vile emendation in Worship III inadvertently reveals the pride behind any refusal to take the word of God, and the Word of God, as they are: “God in us made manifest.” Sorry, but we long to be made holy, not so that we may gaze, Narcissus-like, on our own divine beauty, but so that we can look upon the Lord, and find our beauty in him. By his grace we will then be keener-sighted than the eastern sages, the curious onlookers at the Jordan, the sick in soul and body, and the many foes and the few friends beneath the cross. We will see him, says St. John, as he is. Nothing need be added to that; nor let anything be detracted. Here, as is just, the poet ends:

Grant us grace to see thee, Lord,

Mirrored in thy holy word;

May we imitate thee now,

And be pure, as pure art thou;

That we like to thee may be

At thy great epiphany;

And may praise thee, ever blest,

God in man made manifest. •

Read more: http://www.touchstonemag.com/archives/article.php?id=25-01-010-c#ixzz4VN8nzc6l