Mount Calvary Church

Eutaw Street and Madison Avenue

Baltimore, Maryland

A Parish of the Roman Catholic Personal Ordinariate of St. Peter

Anglican Use

Rev. Albert Scharbach, Pastor

Lent I

February 18, 2018

8:00 AM Said Mass

10:00 AM Sung Mass

____________________________

The Great Litany in Procession

Hymns

O love, how deep, how broad, how high

Forty days and forty nights

Anthems

A Litany, William Walton

Miserere mei, William Byrd

_______________________________

The Great Litany

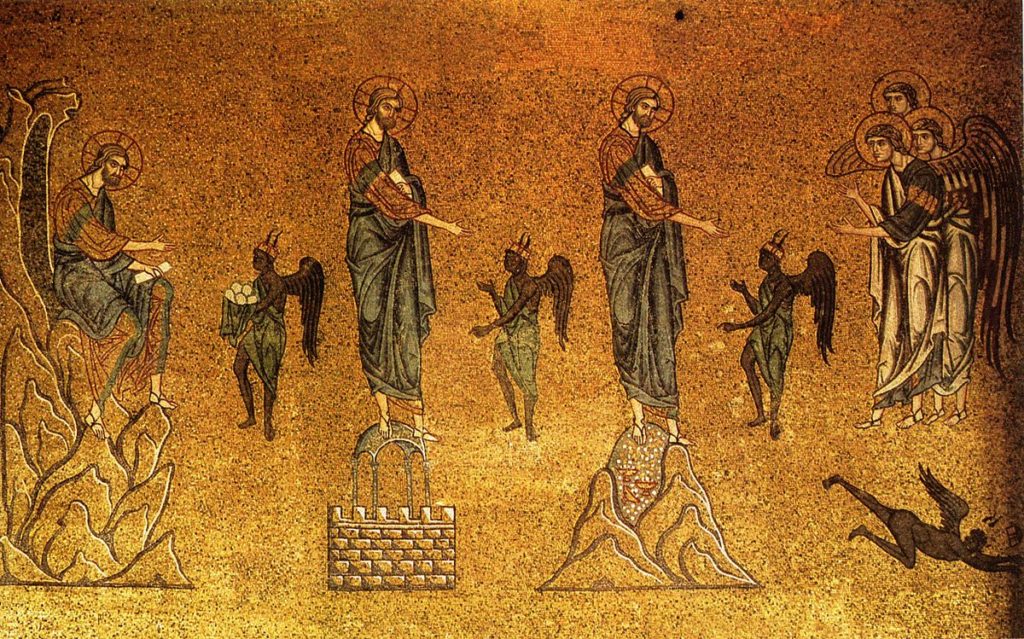

The Great Litany was the first service written in English. It was composed by Thomas Cranmer in 1544 from older litanies: the Sarum rite litany, a Latin litany composed by Martin Luther, and the Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom. The word litany comes from the Latin litania, from the Greek litê, meaning “prayer” or “supplication.”

After invoking the Trinity, we ask to be delivered from the evils that come upon us because of sin: heresy, schism, natural disasters, political disasters, war, violence, murder, sudden death.

Litanies are penitential exercises. They are the urgent supplications of the people of God suffering under or dreading divine judgements and asking to be spared or delivered from calamities which at the same time they confess that they deserve. This form of the fear of the Lord is characteristic of the prophets of Israel.

Whatever our control of nature may be, it remains true that we are in the hands of a Power beyond us. Both our reason and our faith drive us to the recognition that this governing Power is a personal God and a righteous God who visits men and nations with judgements on their sins; though we may, if we choose, blind our eyes to the evidences of divine judgement and neglect that humble and penitent return to God which they are intended to stimulate. This Lent let us in penitence turn to Him that we may turn away from evil and be spared His righteous judgement.

Here is the Great Litany at St. John’s, Detroit.

____________________________________________

Hymns

O love, how deep, how broad, how high

O Love, how deep, how broad, how high is a translation by Benjamin Webb (1819–1885) of the text O amor quam exstaticus, from a 15th c. Latin poem written by someone influenced by the Devotio Moderna and Thomas à Kempis.

1 O love, how deep, how broad, how high,

how passing thought and fantasy,

that God, the Son of God, should take

our mortal form for mortals’ sake!2 He sent no angel to our race,

of higher or of lower place,

but wore the robe of human frame,

and He Himself to this world came.3 For us baptized, for us He bore

His holy fast, and hungered sore;

for us temptations sharp He knew,

for us the tempter overthrew.4 For us to wicked men betrayed,

scourged, mocked, in crown of thorns arrayed,

He bore the shameful cross and death

for us at length gave up His breath.5 For us He rose from death again,

for us He went on high to reign,

for us He sent His Spirit here

to guide, to strengthen, and to cheer.6 All glory to our Lord and God

for love so deep, so high, so broad —

the Trinity whom we adore

forever and forevermore.

Here is St. Bartholomew’s.

Webb was an Anglican clergyman, a member of the Cambridge Camden Society which studied medieval art and liturgy, and a close friend of his fellow student at Trinity, John Mason Neale.

_____________________________

Forty days and forty nights

The Anglican clergyman George Hunt Smyttan (1822-1870) wrote a poem, which was published in the March 1856 edition of The Penny Post and was revised five years later as Forty Days and Forty Nights in Hymns Fitted to the Order of Common Prayer (1861), by the Rev. Francis Pott (1832–1909).

1 Forty days and forty nights

you were fasting in the wild;

forty days and forty nights

tempted, and yet undefiled.2 Shall not we your sorrow share

and from worldly joys abstain,

fasting with unceasing prayer,

strong with you to suffer pain?3 Then if Satan on us press,

flesh or spirit to assail,

victor in the wilderness,

grant that we not faint nor fail!4 So shall we have peace divine:

holier gladness ours shall be;

round us, too, shall angels shine,

such as served you faithfully.5 Keep, O keep us, Savior dear,

ever constant by your side,

that with you we may appear

at the eternal Eastertide.

Here it is sung at Compline. Here is Bradford Cathedral.

____________________________________________________________

Anthems

A Litany, William Walton

Drop, Drop, slow tears, And bathe those beauteous feet,Which brought from heav’n The news and Prince of Peace: Cease not, wet eyes, His mercy to entreat; To cry for vengeance, Sin doth never cease. In your deep floods Drown all my faults and fears; Nor let His eye See sin, but through my tears.

Here is the USC Chamber Choir.

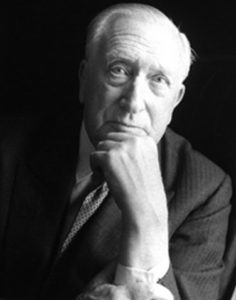

Perhaps nowhere is William Walton’s precocity evidenced as clearly as in his Litany (1916) — composed when he was only 15 years old. The work is a setting of a devotional text by seventeenth-century writer Phineas Fletcher, whose penitential poetry finds evocative realization in Walton’s a cappella rendering. Walton scholars note the skill demonstrated by the composer’s voice leading; his harmonic choices, while not necessarily possessing the measured dramatic weight of a mature composer, certainly do not seem the work of an adolescent. Particularly effective is the ambiguous harmony with which the piece begins: a dissonant and disorienting augmented chord, followed by a closely overlapping and likewise dissonant diminished chord, which finally settles at the fourth bar into the E minor harmony upon which the work is built.

Homophonic declamation generally predominates, though various other textures are employed with poignant effects. First and foremost is the pictorial rendering of the repeated word “Drop,” which Walton sets as a descending sequence of leaps in the soprano. Elsewhere, polyphonic divergence sets up moments of tension, as in the “cry for vengeance” of the second stanza. Some observe in the final cadence a foreshadow of the kind of harmonic practice Walton would utilize in later works; the final resolution to an E minor triad is approached and made all the more resolute by a handful of shimmeringly dissonant half steps.

The poem is by the English poet, priest and metaphysician, Phineas Fletcher, (1582-1650) who earned a B.A. in 1604 and M.A. in 1608 from King’s College, Cambridge. By 1611 he had become a fellow at the college. He was known for pastorals and theological poetry. In A Litany, Fletcher’s speaker is hoping to weap enough that the tears will wash Christ’s feet to satisfaction; hoping that the tears will purge relentless sin; that the Lord shall not “See sin, but through my tears.”

Sir William Walton (1902-1983) was a significant composer of orchestral music and one of the major figures to emerge in England between Vaughan Williams and Britten. Born to a family of professional musicians, Walton began his musical studies singing anthems in his father’s Anglican church choir. His output was varied, ranging from the Viola Concerto and the colorful and impressive cantata ‘Belshazzar’s Feast,’ to small choral pieces such as ‘A Litany.’

_____________________

Miserere mei, William Byrd

Miserere mei Deus, secundum magnam misericordiam tuam, et secundum multitudinem miserationum tuarum, delle iniquitatem meam.

Have mercy on me, O God, according to thy great mercy. According to the multitude of thy commiserations, take away mine iniquity.

Here is the Worcester College Chapel Choir, Oxford.

William Byrd maintained a precarious position as a Catholic in Protestant England. He dutifully provided Protestant church music of a very high caliber, as well as a wealth of courtly instrumental and vocal music. The resultant favor of the Queen and the potency of his noble patrons also allowed Byrd to compose and print music for the Catholic liturgy under his own name, even during times of crackdown when possession of the same books could be grounds for suspicion and arrest. In 1591, the year of his retirement to a recusant Catholic home in Stondon Massey, Byrd released through the press of Thomas East the second volume of his Cantiones sacrae, containing Miserere mei Deus and 20 other Latin motets. It seems that his intention in the print was twofold: he was first providing functional music for domestic performance in the private chapels of his Catholic patrons such as Sir John Petre and Edward Somerset. At the same time, the careful ordering of music within the 1591 print, which creates a large-scale modal descent through several keys, and the overwhelming number of mournful texts Byrd selected, suggest he was also expressing his own spiritual travail.

Miserere mei Deus shows both of these characteristics. Though Byrd set the plaintive text from Psalm 51 to a full five-voiced texture, only the two tenor parts are particularly broad in range, and the composer’s frequent recourse to chordal homophony makes Miserere mei Deus quite accessible (perfect for domestic performance). At the same time, Byrd took a lot of care in crafting the little motet. It concludes the five-voiced section of the 1591 printed anthology, and thus represents the deepest modal descent, into a G mode with fully two flats in its key signature; it does, however, begin quite naturally as an echo to the final chord of the preceding motet, Exsurge Domine. And despite the superficial simplicity of the music, Byrd wrought in it a powerfully affective cry for God’s mercy. It opens with two homophonic invocations to God, unified in texture and poignancy of cadence (plagal and Phrygian). The composer breaks into polyphony in the following phrase, “according to thy great mercy”; the imitative motives both rise aspirantly upwards and offer a subtle pun on the Latin secundum (after). A second homophonic passage is again answered with polyphony, this time a painfully extended passage of repeated cries, each reiterating the manifold sins of those praying for release.