Mount Calvary Church

Baltimore

Personal Ordinariate of the Chair of St. Peter

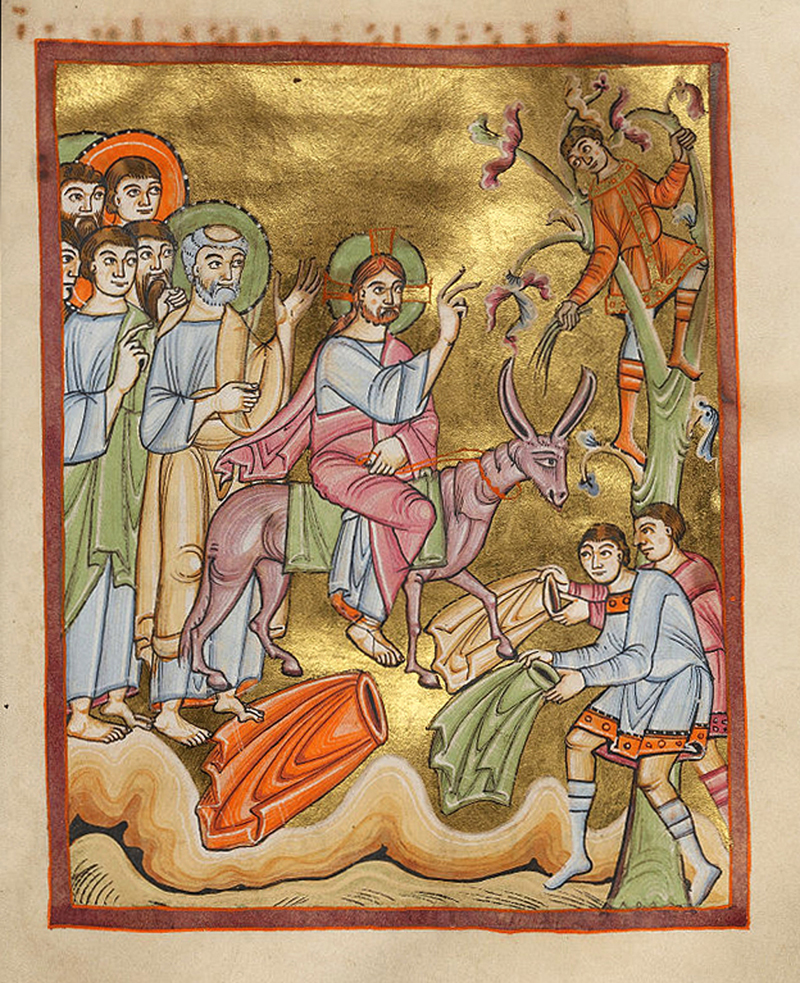

Palm Sunday

April 9, 2017

Hymns

All glory, laud, and honor

O sacred head, sore wounded

Ride on, ride on in majesty

Anthems

Pueri hebraeprum, Tomás Luis de Victoria

Ode I, Triodion, Arvo Pärt

Common

Sanctus, Agnus Dei, Missa Brevis, Palestrina

____________________________

All glory, laud and honor was written by St. Theodulph of Orleans in 820 while he was imprisoned in Angers, France, for conspiring against the King, with whom he had fallen out of favor. It was translated by John Mason Neale. The text is a retelling of the triumphal entry of Jesus into Jerusalem. The medieval church re-enacted this story on Palm Sunday. The priests and inhabitants of a city would process from the fields to the gate of the city, following a living representation of Jesus seated on a donkey. When they reached the city gates, a choir of children would sing this hymn, then in Latin: Gloria, laus et honor, and the refrain was taken up by the crowd. At this point the gates were opened and the crowd made its way through the streets to the cathedral. Today we praise the “Redeemer, King” because we know just what kind of King He was and is – an everlasting King who reigns not just in Jerusalem, but over the entire earth. What else can we do but praise Him with glory, laud, and honor.

All glory, laud, and honour

to thee, Redeemer, King,

to whom the lips of children

made sweet hosannas ring.Thou art the King of Israel,

thou David’s royal Son,

who in the Lord’s name comest,

the King and blessed one: [Refrain]The company of angels

are praising thee on high,

and mortal men and all things

created make reply: [Refrain]The people of the Hebrews

with palms before thee went:

our praise and prayer and anthems

before thee we present: [Refrain]To thee before thy passion

they sang their hymns of praise:

to thee now high exalted

our melody we raise: [Refrain]Thou didst accept their praises,

accept the prayers we bring,

who in all good delightest,

thou good and gracious King: [Refrain]

Here it is sung by the choir of King’s College, Cambridge.

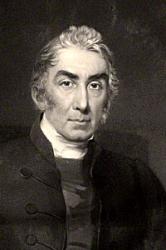

John Mason Neale in cassock

John Mason Neale, D.D., the translator of Honor, laus, et gloria (1818—1866) was the son of the Rev. Cornelius Neale, and Fellow of St. John’s College, Cambridge, ” The father died in 1823, and the boy’s early training was entirely under the direction of his mother, a devout Evangelical. At Cambridge he identified himself with the Church movement, which was spreading there in a quieter, but no less real, way than at Oxford. He became one of the founders of the Ecclesiological, or, as it was commonly called, the Cambridge Camden Society, in conjunction with Mr. E. J. Boyce, his future brother-in-law, and Mr. Benjamin Webb, afterwards the well-known Vicar of St. Andrew’s, Wells Street, and editor of The Church Quarterly Review.. In the quiet retreat of East Grinstead, therefore, Dr. Neale spent the remainder of his comparatively short life writing in support of the Oxford movement and caring for the Anglican congregation he had founded, the Sisterhood of St. Margaret’s. Dr. Neale met with many difficulties, and great opposition from the outside, which, on one occasion, if not more, culminated in actual violence. In 1857 he was attending the funeral of one of the Sisters at Lewes, when a report was spread that the deceased had been decoyed into St. Margaret’s Home, persuaded to leave all her money to the sisterhood, and then purposely sent to a post in which she might catch the scarlet fever of which she died. Dr. Neale and some Sisters who were attending the funeral were attacked and roughly handled by a mob.

His window in St. Swithuns, East Grinstead

This is the original:

GLORIA, laus et honor

tibi sit, Rex Christe, Redemptor:

Cui puerile decus prompsit

Hosanna pium. R.Israel es tu Rex, Davidis et

inclyta proles:

Nomine qui in Domini,

Rex benedicte, venis.Coetus in excelsis te laudat

caelicus omnis,

Et mortalis homo, et cuncta

creata simul.Plebs Hebraea tibi cum palmis

obvia venit:

Cum prece, voto, hymnis,

adsumus ecce tibi.Hi tibi passuro solvebant

munia laudis:

Nos tibi regnanti pangimus

ecce melosHi placuere tibi, placeat

devotio nostra:

Rex bone, Rex clemens, cui

bona cuncta placent.

Her is the Gregorian setting of the Latin..

Theodulf was born in Spain, probably Saragossa, between 750 and 760, and was of Visigothic descent. He fled Spain because of the Moorish occupation of the region and traveled to the South-Western province of Gaul called Aquitaine, where he received an education. He went on to join the monastery near Maguelonne in Southern Gaul led by the abbot Benedict of Aniane. During his trip to Rome in 786, Theodulf was inspired by the centres of learning there, and sent letters to a large number of abbots and bishops of the Frankish empire, encouraging them to establish public schools.

Charlemagne recognized Theodulf’s importance within his court and simultaneously named him Bishop of Orléans (c. 798) and abbot of many monasteries, most notably the Benedictine abbey of Fleury-sur-Loire.[5] He then went on to establish public schools outside the monastic areas which he oversaw, following through on this idea that had impressed him so much during his trip to Rome. Theodulf quickly became one of Charlemagne’s favoured theologians alongside Alcuin of Northumbria and was deeply involved in many facets of Charlemagne’s desire to reform the church, for example by editing numerous translated texts that Charlemagne believed to be inaccurate and translating sacred texts directly from the classical Greek and Hebrew languages. He was a witness to the emperor’s will in 811.

Charlemagne died in 814 and was succeeded by his son Louis the Pious. Louis’ nephew, King Bernard of Italy, sought independence from the Frankish empire and raised his army against the latter. Bernard was talked into surrendering, but was punished by Louis severely, sentencing him to have his sight removed. The procedure of blinding Bernard went wrong and he died as a result of the operation. Louis believed that numerous people in his court were conspiring against him with Bernard, and Theodulf was one of many who were accused of treason. He was forced to abandon his position of Bishop of Orléans in 817 and was exiled to a monastery in Angers in 818 where he spent the next two years of his life. After he was released in 820, he tried to reclaim his bishopric in Orléans but was never able to reach the city because it is believed that he died during the trip in 821 and his body was brought back to Angers where it was buried, (Wikipedia, alt.)

Now often named ST. THEODULPH because of its association with this text, the tune is also known, especially in organ literature, as VALET WILL ICH DIR GEBEN. It was composed by Melchior Teschner (b. Fraustadt [now Wschowa, Poland], Silesia, 1584; d. Oberpritschen, near Fraustadt, 1635) for “Valet will ich dir geben,” Valerius Herberger’s hymn for the dying. Teschner composed the tune in two five-voice settings, published in the leaflet Ein andächtiges Gebet in 1615.

Teschner studied philosophy, theology, and music at the University of Frankfurt an-der-Oder and later studied at the universities of Helmstedt and Wittenberg, Germany. From 1609 until 1614 he served as cantor in the Lutheran church in Fraustadt, and from 1614 until his death he was pastor of the church in Oberpritschen.

The first stanza of the German text is

Valet will ich dir geben

Du arge, falsche Welt;

Dein sündlich böses Leben

Durchaus mir nicht gefällt.

Im Himmel ist gut wohnen,

Hinauf zieht mein Begier;

Da wird Gott herrlich lohnen

Dem, der ihm dient allhier.

Bach used the text and melody in Christus der ist mein Leben (BWV 95) and in the St. John’s Passion (BWV 245).

____________________

Dürer, c. 1509

O sacred head sore wounded was composed by Paul Gerhardt (1607—1676), who closely modeled it after a stanza of a poem, Salve mundi salutare, possibly by St. Bernard of Clairvaux (1091-1153) or Arnulf of Leuwen, which contains seven stanzas meditating on how the different parts of Jesus’ body suffered during the Passion. The head is the seat of honor, “face,” and was insulted by a mocking crown of thorns, by spit, and blows from fists. Yet it is the vision of that face that will be our happiness and joy forever, for He has born all our guilt and shame, and given us His life.

O sacred head, sore wounded,

Defiled and put to scorn;

O kingly head, surrounded

With mocking crown of thorn:

What sorrow mars Thy grandeur?

Can death Thy bloom deflow’r?

O countenance whose splendor

The hosts of heav’en adore!2 Thy beauty, long desired,

Hath vanished from our sight;

Thy pow’r is all expired,

And quenched the light of light.

Ah me! for whom Thou diest,

Hide not so far Thy grace:

Show me, O Love most highest,

The brightness of Thy face.3 In Thy most bitter passion

My heart to share doth cry,

With Thee for my salvation

Upon the cross to die.

Ah, keep my heart thus moved

To stand Thy cross beneath,

To mourn Thee, well-beloved,

Yet thank Thee for Thy death.4 What language shall I borrow

To thank Thee, dearest friend,

For this Thy dying sorrow,

Thy pity without end?

Oh, make me Thine for ever!

And should I fainting be,

Lord, let me never, never

Outlive my love for Thee.5 My days are few, O fail not,

With Thine immortal pow’r,

To hold me that I quail not

In death’s most fearful hour;

That I may fight befriended,

And see in my last strife

To me Thine arms extended

Upon the cross of life.

The Latin text on which the hymn is based is:

Salve mundi salutare, Ad faciem:

Salve, caput cruentatum,

totum spinis coronatum,

conquassatum, vulneratum,

arundine verberatum,

facie sputis illita.

salve, cujus dulcis vultus,

immutatus et incultus,

immutavit suum florem,

totus versus in pallorem

quem […] coeli curia.

Omnis vigor atque viror

hinc recessit, non admiror,

mors apparet in aspectu

totus pendens in defectu,

attritus aegra macie.

sic affectus, sic despectus,

propter me sic interfectus,

peccatori tam indigno

cum amoris intersigno

appare clara facie.

In hac tua passione,

me agnosce, pastor bone,

cujus sumpsi mel ex ore,

haustum lactis cum dulcore,

prae omnibus deliciis.

non me reum asperneris,

nec indignum dedigneris,

morte tibi jam vicina,

tuum caput hic inclina,

in meis pausa brachiis.

Tuae sanctae passioni

me gauderem interponi,

in hac cruce tecum mori:

praesta crucis amatori,

sub cruce tua moriar.

morti tuae tam amarae

grates ago, Jesu chare;

qui es clemens, pie Deus,

fac quod petit tuus reus,

ut absque te non finiar.

Dum me mori est necesse,

noli mihi tunc deesse;

in tremenda mortis hora

veni, Jesu, absque mora,

tuere me et libera.

cum me jubes emigrare,

Jesu chare, tunc appare:

o amator amplectende,

temetipsum tunc ostende

in cruce salutifera.

Here is a translation of the Latin:

I Hail, bleeding Head of Jesus, hail to Thee! Thou thorn-crowned Head, I humbly worship Thee! O wounded Head, I lift my hands to Thee; O lovely Face besmeared, I gaze on Thee; O bruised and livid Face, look down on me!

II Hail, beauteous Face of Jesus, bent on me, Whom angel choirs adore exultantly! Hail, sweetest Face of Jesus, bruised for me– Hail, Holy One, whose glorious Face for me Is shorn of beauty on that fatal Tree!

III All strength, all freshness, is gone forth from Thee: What wonder! Hath not God afflicted Thee, And is not death himself approaching Thee? O Love! But death hath laid his touch on Thee, And faint and broken features turn to me.

IV O have they thus maltreated Thee, my own? O have they Thy sweet Face despised, my own? And all for my unworthy sake, my own! O in Thy beauty turn to me, my own; O turn one look of love on me, my own!

V In this Thy Passion, Lord, remember me; In this Thy pain, O Love, acknowledge me; The honey of whose lips was shed on me, The milk of whose delights hath strengthened me Whose sweetness is beyond delight for me!

VI Despise me not, O Love; I long for Thee; Contemn me not, unworthy though I be; But now that death is fast approaching Thee, Incline Thy Head, my Love, my Love, to me, To these poor arms, and let it rest on me!

VII The holy Passion I would share with Thee, And in Thy dying love rejoice with Thee; Content if by this Cross I die with Thee; Content, Thou knowest, Lord, how willingly Where I have lived to die for love of Thee.

VIII For this Thy bitter death all thanks to Thee, Dear Jesus, and Thy wondrous love for me! O gracious God, so merciful to me, Do as Thy guilty one entreateth Thee, And at the end let me be found with Thee!

IX When from this life, O Love, Thou callest me, Then, Jesus, be not wanting unto me, But in the dreadful hour of agony, O hasten, Lord, and be Thou nigh to me, Defend, protect, and O deliver me.

X When Thou, O God, shalt bid my soul be free, Then, dearest Jesus, show Thyself to me! O condescend to show Thyself to me,– Upon Thy saving Cross, dear Lord, to me,– And let me die, my Lord, embracing Thee!

Membra Jesu Nostri, The Limbs of Our Jesus, (BuxVW 75), is a cycle of seven cantatas composed by Dieterich Buxtehude in 1680. This work is the first Lutheran oratorio. The main text is from Salve mundi salutare – also known as the Rhythmica oratio . It is divided into seven parts, each addressed to a different part of Christ’s crucified body: feet, knees, hands, sides, breast, heart, and head (ad faciem)

Arnulf of Leuven (c. 1200–1250) was the abbot of the Cistercian in Villers-la-Ville. After serving in this office for ten years, he abdicated, hoping to pursue a life devoted to study and asceticism. He is now consider the probable author of Salve mundi salutare.

PASSION CHORALE: The music for the German and English versions of the hymn is by Hans Leo Hassler, written around 1600 for a secular love song, “Mein G’müt ist mir verwirret” (My heart is distracted by a gentle maid), which first appeared in print in the 1601 Lustgarten neuer teutscher Gesäng, Balletti, Galliarden und Intraden. The tune was appropriated and rhythmically simplified for Gerhardt’s German hymn in 1656 by Johann Crüger. It first appeared with the Gerhardt text in Praxis Pietatis Melica (1656). Johann Sebastian Bach arranged the melody and used five stanzas of the hymn in the St Matthew Passion. He also used the hymn’s text and melody in the second movement of the cantata Sehet, wir gehn hinauf gen Jerusalem (BWV 159). Bach used the melody on different words in his Christmas Oratorio, in the first part (no. 5). Franz Liszt included an arrangement of this hymn in the sixth station, Saint Veronica, of his Via Crucis. The Danish composer Rued Langgaard composed a set of variations for string quartet on this tune. It is also employed in the final chorus of “Sinfonia Sacra”, the 9th symphony of the English composer Edmund Rubbra. Peter Paul and Mary used the tune in their Because all men are brothers and Paul Simon used it in “American Tune.”

___________________

Ride on, ride on in majesty! was written by the Anglican clergyman and Oxford Professor of Poetry Henry Hart Milman (1791–1868). The text unites meekness and majesty, sacrifice and conquest, suffering and glory – all central to the gospel for Palm Sunday. Each stanza begins with “Ride on, Ride on in majesty.” Majesty is the text’s theme as the writer helps us to experience the combination of victory and tragedy that characterizes the Triumphal Entry. Jesus is hailed with “Hosanna” as he rides forth to be crucified. That death spells victory: it is His triumph “o’er captive death and conquered sin.” The angelic powers look down in awe at the coming sacrifice and God the Father awaits His Son’s victory with expectation. Finally, Jesus rides forth to take his “power … and reign!” On the Cross He has defeated death and when He comes in glory to reign He will destroy it forever.

1 Ride on, ride on in majesty!

Hark, all the tribes hosanna cry:

O Saviour meek, pursue thy road

with palms and scattered garments strowed.

2 Ride on, ride on in majesty!

In lowly pomp ride on to die:

O Christ, thy triumphs now begin

o’er captive death and conquered sin.

3 Ride on, ride on in majesty!

The wingèd squadrons of the sky

look down with sad and wondering eyes

to see the approaching sacrifice.

4 Ride on, ride on in majesty!

The last and fiercest strife is nigh:

the Father on his sapphire throne

awaits his own anointed Son.

5 Ride on, ride on in majesty!

In lowly pomp ride on to die;

bow thy meek head to mortal pain,

then take, O God, thy power, and reign.

As an Englishman Milman thought the donkey should not be ignored, and the first stanza originally was:

Ride on, ride on in majesty! Hark, all the tribes hosanna cry; Thine humble beast pursues his road. With palms and scattered garments strowed.

Henry Hart Milman

Henry Hart Milman (1791-1868) was born in London, the third son of Sir Francis Milman, 1st Baronet, physician to King George III. He was educated at Eton and at Brasenose College, Oxford where he won the Newdigate prize with a poem on the Apollo Belvidere in 1812, was elected a fellow of Brasenose in 1814, and in 1816 won the English essay prize with his Comparative Estimate of Sculpture and Painting. In 1816 he was ordained, and two years later became parish priest of St Mary’s, Reading.

In 1821 Milman was elected professor of poetry at Oxford; and in 1827 he delivered the Bampton lectures on “The character and conduct of the Apostles considered as an evidence of Christianity.” In 1835, Sir Robert Peel made him Rector of St Margaret’s, Westminster, and Canon of Westminster, and in 1849 he became Dean of St Paul’s. He was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1864.

Milman made his appearance as a dramatist with his tragedy Fazio (produced on the stage under the title of The Italian Wife). He also wrote Samor, The Lord of The Bright City, the subject of which was taken from British legend, the “bright city” being Gloucester. In subsequent poetical works he was more successful, notably The Fall of Jerusalem (1820) and The Martyr of Antioch (1822, based on the life of Saint Margaret the Virgin), which was used as the basis for an oratorio by Arthur Sullivan. The influence of Byron is seen in his Belshazzar (1822). Another tragedy, Anne Boleyn, followed in 1826. Milman also wrote “When our heads are bowed with woe,” and “Ride on, ride on, in majesty”; a version of the Sanskrit episode of Nala and Damayanti; and translations of the Agamemnon of Aeschylus and the Bacchae of Euripides. His poetical works were published in three volumes in 1839.

Turning to another field, Milman published in 1829 his History of the Jews, which is memorable as the first by an English clergyman which treated the Jews as an Oriental tribe, recognized sheikhs and amirs in the Old Testament, sifted and classified documentary evidence, and evaded or minimized the miraculous. In consequence, the author was attacked and his preferment was delayed. His History of Christianity to the Abolition of Paganism in the Roman Empire (1840) had been completely ignored; but the continuation of his major work, the History of Latin Christianity (1855), which has passed through many editions, was well received. In 1838 he had edited Edward Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, and in the following year published his Life of Gibbon.

When he died he had almost finished a history of St Paul’s Cathedral, which was completed and published by his son, A. Milman (London, 1868), who also collected and published in 1879 a volume of his essays and articles. Milman was buried in the crypt of St. Paul’s Cathedral, where his grave was marked by an elaborate tomb. When the Chapel of the Order of the British Empire was created, the original tomb was replaced by a slab in the floor. Sic transit. (Wikipedia, alt.)

The tune WINCHESTER NEW originally appeared as the melody to “Wer nur den lieben Gott lässt walten,” in the Musicalisch Handbuch der Geistlichen Melodien, Hamburg, 1690. Because it was also used for a hymn, “Dir, dir, Jehovah, will ich singen,” whose words were written by Bartholomäus Crasselius (1667–1724), the tune is sometimes erroneously ascribed to him.

Here is the choir of King’s College, Cambridge.

____________________

It will be noted that all three hymns today are contrafacta, as they are the product of the substitution of one text for another without substantial change to the music. In particular, the tune of O sacred head was originally a love song.

____________________

The Offertory Anthem for Palm Sunday will be Tomás Luis de Victoria’s (1548-1611) Pueri Hebraeorum. Victoria used motifs from Gregorian chants to construct motet, which respects and brings out the emotional implications of the Latin text. The counterpoint indicates to us how the Jewish children grouped themselves around Him whom they wished to acclaim. The rhythmic syncopations describe how the children threw their garments on the road, “in via.” The acclamations, “Benedictus”, are introduced in intervals of ascending fourths imitating canonically the first section of the motet.

____________________

The Communion Anthem for Palm Sunday will be the first Ode from Arvo Pärt’s Triodion: O Jesus the Son of God, Have Mercy Upon Us. The Ode is rhythmically static, while harmonic movement similarly ceases in the final supplications, where Pärt’s music can be heard at its starkest and most unadorned.

O Jesus the Son of God, Have Mercy Upon Us. We do homage to Thy pure image, O Good One, entreating forgiveness of our transgressions, O Christ our God: for of Thine own good will Thou wast graciously pleased to ascend the Cross in the flesh, that Thou mightest deliver from bondage to the enemy those whom Thou hadst fashioned. For which cause we cry aloud unto Thee with thanksgiving; with joy has Thou filled all things, O our Saviour, in that Thou didst come to save the world.

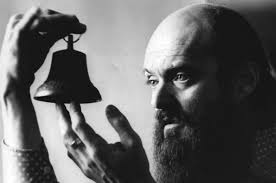

Arvo Pärt

Arvo Pärt (1935- ) is an Estonian composer. Since the late 1970s, Pärt has worked in a minimalist style that employs his self-invented compositional technique, Tintinnabuli, which was influenced by the composer’s experiences with chant. It is characterized by two types of voice, the first of which (dubbed the “tintinnabular voice”) arpeggiates the tonic triad , and the second of which moves diatonically in stepwise motion. The works often have a slow and meditative tempo, and a minimalist approach to both notation and performance.

Pärt’s music has similarities and differences from the great polyphonists like Victoria: a diatonic idiom with a slow harmonic turnover, no modulation, much use of the triad, an uncluttered background to the writing which emphasizes its stillness, and a deep respect for silence. The differences in style between Pärt and the Renaissance masters are Pärt’s lack of interest in counterpoint, and the chord clusters which derive from tintinnabuli. Pärt’s melodies tend to come one at a time, unwinding slowly: his is not a teaming web of melodies, as was commonplace with the best polyphonists. Nor did Palestrina and the others have access to the kind of dissonance which at times so delights Pärt.

Here is the Tallis’s Scholars video on Pärt’s musical style.

(Gratias ago Wikipediā et aliis aliorum plurimorum scriptorum interretialum.)