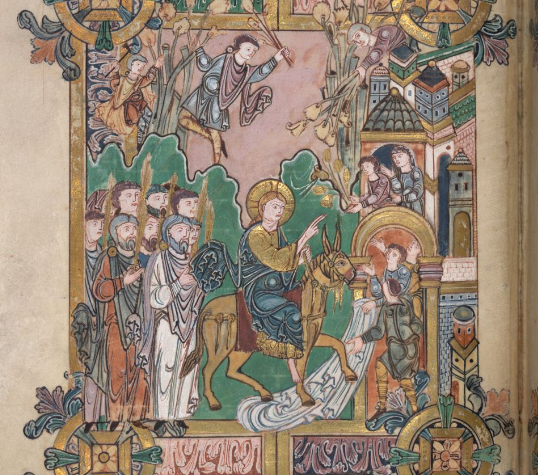

From the Benedictional of St. Aethelwold

Mount Calvary Church

Eutaw Street and Madison Avenue

Baltimore, Maryland

A Parish of the Roman Catholic Personal Ordinariate of St. Peter

Anglican Use

Rev. Albert Scharbach, Pastor

Palm Sunday

March 25, 2018

8:00 AM Said Mass

10:00 AM Sung Mass with Procession of Palms

Common

Missa Aeterna Christi munera, Palestrina

Hymns

All glory, laud, and honor (ST. THEODULPH)

Ah, holy Jesus (HERZLIEBSTER JESU)

Ride on, ride on in majesty (WINCHESTER NEW)

Anthems

Erbarme dich, J. S.Bach

Pueri Hebraeorum, Tomas Luis de Victoria

______________________________

From the Sarum Ritual

“I exorcise thee, O creature of flowers and leaves, in the name of God the Father almighty, and in the name of Jesus Christ His Son our Lord, and in the power of the Holy Ghost. Henceforth all power of the adversary, all the host of the devil, all the strength of the enemy, all assaults of demons, be uprooted and transplanted from this creature of flowers and leaves, that thou pursue not by subtlety the footsteps of those who hasten to the grace of God. Through Him who shall come to judge the quick and dead, and the world by fire. R. Amen.”

______________________________

Common

The Missa Aeterna Christ Munera was written by Palestrina in 1590. iR is based on an ancient hymn of the same name. Palestrina breaks the tune into phrases and elaborates in points of imitation to fit the style and text of the different parts of the mass ordinary. The second setting of the Agnus Dei is particularly beautiful: the texture broadens from four to five parts and teh movement closes with a prayer for peace: dona nobis pacem.

Hymns

All glory, laud, and honor

All glory, laud and honor was written by St. Theodulph of Orleans in 820 while he was imprisoned in Angers, France, for conspiring against the King, with whom he had fallen out of favor. It was translated by John Mason Neale. The text is a retelling of the triumphal entry of Jesus into Jerusalem. The medieval church re-enacted this story on Palm Sunday. The priests and inhabitants of a city would process from the fields to the gate of the city, following a living representation of Jesus seated on a donkey. When they reached the city gates, a choir of children would sing this hymn, then in Latin: Gloria, laus et honor, and the refrain was taken up by the crowd. At this point the gates were opened and the crowd made its way through the streets to the cathedral. Today we praise the “Redeemer, King” because we know just what kind of King He was and is – an everlasting King who reigns not just in Jerusalem, but over the entire earth. What else can we do but praise Him with glory, laud, and honor.

All glory, laud, and honour

to thee, Redeemer, King,

to whom the lips of children

made sweet hosannas ring.Thou art the King of Israel,

thou David’s royal Son,

who in the Lord’s name comest,

the King and blessed one: [Refrain]The company of angels

are praising thee on high,

and mortal men and all things

created make reply: [Refrain]The people of the Hebrews

with palms before thee went:

our praise and prayer and anthems

before thee we present: [Refrain]To thee before thy passion

they sang their hymns of praise:

to thee now high exalted

our melody we raise: [Refrain]Thou didst accept their praises,

accept the prayers we bring,

who in all good delightest,

thou good and gracious King: [Refrain]

Here it is sung by the choir of King’s College, Cambridge.

John Mason Neale in cassock

John Mason Neale (1818—1866), the translator of Honor, laus, et gloria was the son of the Rev. Cornelius Neale. The father died in 1823, and the boy’s early training was entirely under the direction of his mother, a devout Evangelical. At Cambridge he identified himself with the Church movement, which was spreading there in a quieter, but no less real, way than at Oxford. He became one of the founders of the Ecclesiological, or, as it was commonly called, the Cambridge Camden Society, in conjunction with Mr. E. J. Boyce, his future brother-in-law, and Mr. Benjamin Webb, afterwards the well-known Vicar of St. Andrew’s, Wells Street, and editor of The Church Quarterly Review. In the quiet retreat of East Grinstead, Dr. Neale spent the remainder of his comparatively short life writing in support of the Oxford movement and caring for the Anglican congregation he had founded, the Sisterhood of St. Margaret’s. Dr. Neale met with many difficulties, and great opposition from the outside, which, on one occasion culminated in actual violence. In 1857 he was attending the funeral of one of the Sisters at Lewes, when a report was spread that the deceased had been decoyed into St. Margaret’s Home, persuaded to leave all her money to the sisterhood, and then purposely sent to a post in which she might catch the scarlet fever of which she died. Dr. Neale and some Sisters who were attending the funeral were attacked and roughly handled by a mob.

His window in St. Swithuns, East Grinstead

This is the original:

GLORIA, laus et honor

tibi sit, Rex Christe, Redemptor:

Cui puerile decus prompsit

Hosanna pium. R.Israel es tu Rex, Davidis et

inclyta proles:

Nomine qui in Domini,

Rex benedicte, venis.Coetus in excelsis te laudat

caelicus omnis,

Et mortalis homo, et cuncta

creata simul.Plebs Hebraea tibi cum palmis

obvia venit:

Cum prece, voto, hymnis,

adsumus ecce tibi.Hi tibi passuro solvebant

munia laudis:

Nos tibi regnanti pangimus

ecce melosHi placuere tibi, placeat

devotio nostra:

Rex bone, Rex clemens, cui

bona cuncta placent.

Her is the Gregorian setting of the Latin.

Theodulf, the author of the Latin poem,was born in Spain, probably Saragossa, between 750 and 760, and was of Visigothic descent. He fled Spain because of the Moorish occupation and traveled to the South-Western province of Gaul called Aquitaine, where he received an education. He went on to join the monastery near Maguelonne in Southern Gaul led by the abbot Benedict of Aniane. During his trip to Rome in 786, Theodulf was inspired by the centres of learning there, and sent letters to a large number of abbots and bishops of the Frankish empire, encouraging them to establish public schools.

Charlemagne recognized Theodulf’s importance within his court and simultaneously named him Bishop of Orléans (c. 798) and abbot of many monasteries, most notably the Benedictine abbey of Fleury-sur-Loire. He then went on to establish public schools outside the monastic areas which he oversaw, following through on this idea that had impressed him so much during his trip to Rome. Theodulf quickly became one of Charlemagne’s favoured theologians alongside Alcuin of Northumbria and was deeply involved in many facets of Charlemagne’s desire to reform the church, for example by editing numerous translated texts that Charlemagne believed to be inaccurate and translating sacred texts directly from the classical Greek and Hebrew languages. He was a witness to the emperor’s will in 811.

Charlemagne died in 814 and was succeeded by his son Louis the Pious. Louis’ nephew, King Bernard of Italy, sought independence from the Frankish empire and raised his army against the latter. Bernard was talked into surrendering, but was punished by Louis severely, sentencing him to have his sight removed. The procedure of blinding Bernard went wrong and he died as a result of the operation. Louis believed that numerous people in his court were conspiring against him with Bernard, and Theodulf was one of many who were accused of treason. He was forced to abandon his position of Bishop of Orléans in 817 and was exiled to a monastery in Angers in 818 where he spent the next two years of his life. After he was released in 820, he tried to reclaim his bishopric in Orléans but was never able to reach the city because it is believed that he died during the trip in 821 and his body was brought back to Angers where it was buried.

Now often named ST. THEODULPH because of its association with this text, the tune is also known, especially in organ literature, as VALET WILL ICH DIR GEBEN. It was composed by Melchior Teschner (b. Fraustadt [now Wschowa, Poland], Silesia, 1584; d. Oberpritschen, near Fraustadt, 1635) for “Valet will ich dir geben,” Valerius Herberger’s hymn for the dying. Teschner composed the tune in two five-voice settings, published in the leaflet Ein andächtiges Gebet in 1615.

Teschner studied philosophy, theology, and music at the University of Frankfurt an-der-Oder and later studied at the universities of Helmstedt and Wittenberg, Germany. From 1609 until 1614 he served as cantor in the Lutheran church in Fraustadt, and from 1614 until his death he was pastor of the church in Oberpritschen.

The first stanza of the German text is

Valet will ich dir geben

Du arge, falsche Welt;

Dein sündlich böses Leben

Durchaus mir nicht gefällt.

Im Himmel ist gut wohnen,

Hinauf zieht mein Begier;

Da wird Gott herrlich lohnen

Dem, der ihm dient allhier.

Bach used the text and melody in Christus der ist mein Leben (BWV 95) and in the St. John’s Passion (BWV 245).

___________________________

Ah, holy Jesus

“Herzliebster Jesu” (often translated into English as Ah, Holy Jesus, sometimes as “O Dearest Jesus”) is a German hymn for Passiontide, written in 1630 by Johann Heermann, in 15 stanzas of 4 lines, first published in Devoti Musica Cordis in Breslau. As the original headline reveals, it is based on Augustine of Hippo; this means the seventh chapter of the so-called Meditationes Divi Augustini, presently ascribed to John of Fécamp.

Its tune, also called HERZLIEBSTER JESU, was written ten years later by Johann Crüger and first appeared in Crüger’s Neues vollkömmliches Gesangbuch Augsburgischer Confession. The tune has been arranged many times, including settings by J.S. Bach: one of the Neumeister Chorales for organ, BWV 1093, two movements of the St. John Passion, and three of the St. Matthew Passion. Johannes Brahms used it for one of his Eleven Chorale Preludes for organ, Op. 122: No. 2.[4]). Max Reger’s Passion, No. 4 from his organ pieces Sieben Stücke, Op. 145 (1915–1916), uses this melody.

The translation is by Robert Bridges. Bridges followed Heermann for the first three verses, though loosely (there is no equivalent in line 1 for ‘herzliebster’/ ‘dulcissime’ – most beloved/ most sweet). The two final verses are Bridges’s continuation of the idea: he said that ‘the weak apologetic latter half’ was ‘out of key with the pathetic grief of the beginning’.

1 Ah, holy Jesus, how hast thou offended,

that we to judge thee have in hate pretended?

By foes derided, by thine own rejected,

O most afflicted!

2 Who was the guilty? Who brought this upon thee?

Alas, my treason, Jesus, hath undone thee!

‘Twas I, Lord Jesus, I it was denied thee;

I crucified thee.

3 Lo, the Good Shepherd for the sheep is offered;

the slave hath sinned, and the Son hath suffered.

For our atonement, while we nothing heeded,

God interceded.

4 For me, kind Jesus, was thy incarnation,

thy mortal sorrow, and thy life’s oblation;

thy death of anguish and thy bitter passion,

for my salvation.

5 Therefore, kind Jesus, since I cannot pay thee,

I do adore thee, and will ever pray thee,

think on thy pity and thy love unswerving,

not my deserving.

Here is the Washington National Cathedral choir.

Here is the German:

1 Herzliebster Jesu, was hast du verbrochen,

daß man ein solch scharf Urtheil hat gesprochen?

Was ist die Schuld? In was für Missethaten

bist du gerathen?

2 Du wirst gegeißelt und mit dorn gekrönet,

ins Angesicht geschlagen und verhöhnet;

du wirst mit essig und mit gall getränket

ans Kreuz gehenket.

3 Was ist doch wohl die Urshach solcher Plagen?

Ach! meine Sünden haben dich geschlagen!

Ich, o Herr Jesu! hab dies wohl verschuldet,

was du erduldet!

4 Wie wunderbarlich ist doch diese Strafe!

Der gute Hirte leidet für die Schaafe;

die Schuld bezahlt der Herre, der Gerechte,

für seine Knechte!

5 Der Fromme stirbt, der recht und richtig wandelt;

der Böse lebt, der wider Gott mißhandelt.

Der Mensch verwirkt den Tod, und ist entgangen:

Gott wird gefangen.

6 Ich war von Fuß auf voller Schand und Sünden,

bis zu dem Scheitel war nichts Guts zu finden,

Dafür hätt ich dort in der Höllen müssen

ewiglich büßen.

7 O große Lieb! o Lieb ohn alle Maaße,

die dich gebracht auf diese Marterstraße¡

Ich lebte mit der Welt in Lust und Freuden:

und du must leiden!

8 Ach großer König, groß zu allen Zeiten,

wie kann ich gnugsam solche Treu ausbreiten?

Kein’s Menschen Herz vermag es auszudenken,

was dir zu schenken.

9 Ich kann’s mit meinen Sinnen nicht erreichen,

mit was doch dein Erbarmen zu vergleichen.

Wie kann ich dir denn deine Liebesthaten

im Werk erstatten.

10 Doch ist noch etwas, das dir angenehme:

wann ich des Fleisches Lüste dämpf und zähme;

daß sie aufs neu mein Herze nicht entzünden

mit alten Sünden.

11 Weil’s aber nicht besteht in eignen Kräften,

fest die Begierden an das Kreuz zu heften;

so gieb mir deinen Geist, der mich regiere,

zum Guten führe.

12 Alsdann so werd ich deine Huld betrachten,

aus Lieb an dich die Welt für nichtes achten.

bemühen werd ich mich, Herr, deinen Willen

stets zu erfüllen.

13 Ich werde dir zu Ehren Alles wagen,

kein Kreuz nicht achten, keine Schmach und Plagen,

Nichts von Verfolgung, nichts von Todesschmerzen

nehmen zu Herzen.

14 Dies Alles, obs für schlecht zwar ist zu schätzen,

wirst du es doch nicht gar beiseite setzen.

zu Gnaden wirst du dies von mir annehmen,

mich nicht beschämen.

15 Wann Herre Jesu, dort vor deinem Throne,

wird stehn auf meinen Haupt die Ehrenkrone:

da will ich dir, wenn Alles wird wohl klingen,

Lob und Dank singen.

Johann Heermann (1586-1627), son of Johannes Heermann, a furrier at Baudten, near Wohlau, Silesia, was born at Baudten, Oct. 11, 1585. He was the fifth but only surviving child of his parents, and during a severe illness in his childhood his mother vowed that if he recovered she would educate him for the ministry, even though she had to beg the necessary money. He passed through the schools at Wohlau; at Fraustadt (where he lived in the house of Valerius Herberger, who took a great interest in him); the St. Elizabeth gymnasium at Breslau; and the gymnasium at Brieg. At Easter, 1609, he accompanied two young noblemen (sons of Baron Wenzel von Rothkirch), to whom he had been tutor at Brieg, to the University of Strassburg; but an affection of the eyes caused him to return to Baudten in 1610. At the recommendation of Baron Wenzel he was appointed diaconus of Koben, a small town on the Oder, not far from Baudten, and entered on his duties on Ascension Day, 1611, and on St. Martin’s Day, 1611, was promoted to the pastorate there. After 1623 he suffered much from an affection of the throat, which compelled him to cease preaching in 1634, his place being supplied by assistants. In October, 1638, he retired to Lissa in Posen, and died there on Septuagesima Sunday (Feb. 17), 1647.

Much of Heermann’s manhood was spent amid the distressing scenes of the Thirty Years’ War; and by his own ill health and his domestic trials he was trained to write his beautiful hymns of “Cross and Consolation.” Between 1629 and 1634, Koben was plundered four times by the Lichtenstein dragoons and the rough hordes under Wallenstein sent into Silesia by the King of Austria in order to bring about the Counter-Reformation and restore the Roman Catholic faith and practice; while in 1616 the town was devastated by fire, and in 1631 by pestilence. In these troubled years Heermann several times lost all his moveables; once he had to keep away from Koben for seventeen weeks; twice he was nearly sabred; and once, while crossing the Oder in a frail boat loaded almost to sinking, he heard the bullets of the pursuing soldiers whistle just over his head. He bore all with courage and patience, and he and his were wonderfully preserved from death and dishonour. He was thus well grounded in the school of affliction, and in his House and Heart Music some of his finest hymns are in the section entitled “Songs of Tears. In the time of the persecution and distress of pious Christians.”

As a hymn writer Heermann ranks with the best of his century, some indeed regarding him as second only to Gerhardt. He had begun writing Latin poems about 1605, and was crowned as a poet at Brieg on Oct. 8, 1608. He marks the transition from the objective standpoint of the hymnwriters of the Reformation period to the more subjective and experimental school that followed him. His hymns are distinguished by depth and tenderness of feeling; by firm faith and confidence in face of trial; by deep love to Christ, and humble submission to the will of God. Many of them became at once popular, passed into the hymnbooks, and still hold their place among the classics of German hymnody.

____________________________

Ride on, ride on in majesty

Ride on, ride on in majesty! was written by the Anglican clergyman and Oxford Professor of Poetry Henry Hart Milman (1791–1868). The text unites meekness and majesty, sacrifice and conquest, suffering and glory – all central to the gospel for Palm Sunday. Each stanza begins with “Ride on, Ride on in majesty.” Majesty is the text’s theme as the writer helps us to experience the combination of victory and tragedy that characterizes the Triumphal Entry. Jesus is hailed with “Hosanna” as he rides forth to be crucified. That death spells victory: it is His triumph “o’er captive death and conquered sin.” The angelic powers look down in awe at the coming sacrifice and God the Father awaits His Son’s victory with expectation. Finally, Jesus rides forth to take his “power … and reign!” On the Cross He has defeated death and when He comes in glory to reign He will destroy it forever.

1 Ride on, ride on in majesty!

Hark, all the tribes hosanna cry:

O Saviour meek, pursue thy road

with palms and scattered garments strowed.

2 Ride on, ride on in majesty!

In lowly pomp ride on to die:

O Christ, thy triumphs now begin

o’er captive death and conquered sin.

3 Ride on, ride on in majesty!

The wingèd squadrons of the sky

look down with sad and wondering eyes

to see the approaching sacrifice.

4 Ride on, ride on in majesty!

The last and fiercest strife is nigh:

the Father on his sapphire throne

awaits his own anointed Son.

5 Ride on, ride on in majesty!

In lowly pomp ride on to die;

bow thy meek head to mortal pain,

then take, O God, thy power, and reign.

Here is the choir of King’s College, Cambridge.

As an Englishman Milman thought the donkey should not be ignored, and the first stanza originally was:

Ride on, ride on in majesty! Hark, all the tribes hosanna cry; Thine humble beast pursues his road. With palms and scattered garments strowed.

Henry Hart Milman

Henry Hart Milman (1791-1868) was born in London, the third son of Sir Francis Milman, 1st Baronet, physician to King George III. He was educated at Eton and at Brasenose College, Oxford where he won the Newdigate prize with a poem on the Apollo Belvidere in 1812, was elected a fellow of Brasenose in 1814, and in 1816 won the English essay prize with his Comparative Estimate of Sculpture and Painting. In 1816 he was ordained, and two years later became parish priest of St Mary’s, Reading.

In 1821 Milman was elected professor of poetry at Oxford; and in 1827 he delivered the Bampton lectures on “The character and conduct of the Apostles considered as an evidence of Christianity.” In 1835, Sir Robert Peel made him Rector of St Margaret’s, Westminster, and Canon of Westminster, and in 1849 he became Dean of St Paul’s. He was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1864.

Milman made his appearance as a dramatist with his tragedy Fazio (produced on the stage under the title of The Italian Wife). He also wrote Samor, The Lord of The Bright City, the subject of which was taken from British legend, the “bright city” being Gloucester. In subsequent poetical works he was more successful, notably The Fall of Jerusalem (1820) and The Martyr of Antioch (1822, based on the life of Saint Margaret the Virgin), which was used as the basis for an oratorio by Arthur Sullivan. The influence of Byron is seen in his Belshazzar (1822). Another tragedy, Anne Boleyn, followed in 1826. Milman also wrote “When our heads are bowed with woe,” and “Ride on, ride on, in majesty”; a version of the Sanskrit episode of Nala and Damayanti; and translations of the Agamemnon of Aeschylus and the Bacchae of Euripides. His poetical works were published in three volumes in 1839.

Turning to another field, Milman published in 1829 his History of the Jews, which is memorable as the first by an English clergyman which treated the Jews as an Oriental tribe, recognized sheikhs and amirs in the Old Testament, sifted and classified documentary evidence, and evaded or minimized the miraculous. In consequence, the author was attacked and his preferment was delayed. His History of Christianity to the Abolition of Paganism in the Roman Empire (1840) had been completely ignored; but the continuation of his major work, the History of Latin Christianity (1855), which has passed through many editions, was well received. In 1838 he had edited Edward Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, and in the following year published his Life of Gibbon.

When he died he had almost finished a history of St Paul’s Cathedral, which was completed and published by his son, A. Milman (London, 1868), who also collected and published in 1879 a volume of his essays and articles. Milman was buried in the crypt of St. Paul’s Cathedral, where his grave was marked by an elaborate tomb. When the Chapel of the Order of the British Empire was created, the original tomb was replaced by a slab in the floor. Sic transit. (Wikipedia, alt.)

The tune WINCHESTER NEW originally appeared as the melody to “Wer nur den lieben Gott lässt walten,” in the Musicalisch Handbuch der Geistlichen Melodien, Hamburg, 1690. Because it was also used for a hymn, “Dir, dir, Jehovah, will ich singen,” whose words were written by Bartholomäus Crasselius (1667–1724), the tune is sometimes erroneously ascribed to him.

_________________________________

Anthems

Erbarme dich, J. S. Bach

Erbarme dich, mein Gott, um meiner Zähren willen! Schaue hier, Herz und Auge weint vor dir bitterlich. Erbarme dich, mein Gott.

Have mercy, my God, for the sake of my tears! See here, before you heart and eyes weep bitterly. Have mercy, my God.

Here are Eula Beale and Yehudi Menuhin. Here is Christa Ludwig under Otto Klemperer. And here is Kirsten Flagstad.

In the drama of the Mathaus Pssion, this aria reflects Peter’s solitary heartache in the garden after he denies knowing Jesus three times. It is set in a lilting 12/8 time, suggesting the baroque dance rhythm of the siciliano.

Aching beauty and profound sadness coexist in this music, along with a mix of other emotions which transcend description and literal meaning. The aria follows the account of Peter’s threefold denial of Jesus.The Polish poet and novelist Adam Zagajewski calls Erbarme Dich “the center and the synthesis of western music.” The violinist Yehudi Menuhin called the aria’s lamenting solo violin obligato “the most beautiful piece of music ever written for the violin.”

_____________________________

Pueri Hebraeorum, Tomas Luis de Victoria

Pueri Hebraeorum vestimenta prosternebant in via et clamabant dicentes: Hosanna Filio David, benedictus qui venit in nomine Domini.

The Hebrew children spread their garments in the road, and cried out, saying: Hosanna to the Son of David: blessed is He that cometh in the Name of the Lord.

Tomás Luis de Victoria’s (1548-1611) Pueri Hebraorum. Victoria used motifs from Gregorian chants to construct the motet, which respects and brings out the emotional implications of the Latin text. It captures the energy and excitement of the throng of people welcoming Jesus into Jerusalem.The counterpoint indicates to us how the Jewish children grouped themselves around Him whom they wished to acclaim. The voices enter pone at a time, a common strategy in Renaissance polyphony, here used to convey the size of the crowd,