From the Catacombs of Priscilla

Mount Calvary Church

Personal Ordinariate of the Chair of St. Peter

Fourth Sunday of Easter

The Good Shepherd

May 7, 2017

Hymns

The King of Love my shepherd is

Be joyful, Mary, heavenly Queen

I know that my Redeemer lives

Anthems

Psalm 23, Herbert Howells

Ego sum resurrectione, Hans Leo Hassler

Common

Missa de S. Maria Magdelena, Willan

Credo, Missa de Angelis

_____________________________

Henry Williams Baker (1821-1877) recast George Herbert’s metrical paraphrase of Psalm 23 into this hymn, The King of love my shepherd is. Baker gives Psalm 23 an explicit Christological and sacramental cast. “The streams of living water” flow from Jesus’ pierced side. He ransoms our soul from the captivity of sin, and feeds with food celestial, “the bread which cometh down from heaven, that a man may eat thereof, and not die” On our own we never keep to the righteous paths. That is why Jesus comes in love to us, sinners as we are. In his persistent and tender mercy Jesus seeks us, when, “perverse and foolish,” we stray from Him. The wood of the shepherd’s staff is the wood of the cross that guides the strayed soul. Delights flow from Jesus’ pure chalice. The “wine that gladdens the heart” is the Eucharist, the blood of Christ; His is the chalice that overbrims with love. In the Old Testament, our ancestors in faith longed to dwell in the “house of the Lord,” before the revelation of eternal life was clear. But now Christ fulfills that mysterious longing. He is the Good Shepherd, who “giveth his life for the sheep,” the ultimate gift, eternal life with Him. (Thanks to Tony Esolen)

Here is a Reformed analysis of the hymn:

“We note immediately that the usual way of naming God (“the Lord”) has been replaced with a nonbiblical yet immediately comprehensible allegorical title, “the King of Love.” This unfamiliar opening and the inversion in the first line (“my shepherd is”) prepare the singer for a text that is intentionally—even self-consciously—allusive and aesthetic. This perception of the text is reinforced by the archaic verb forms (“leadeth,” “feedeth”) and the Latinate diction (“verdant,” “celestial”) in the second stanza. The third stanza intensifies the Christological overtones of this paraphrase with allusions not only to the Good Shepherd passage noted earlier but also to Jesus’ parable of the Lost Sheep (Luke 15:4-7; cf. Matthew 18:12-14). The fourth stanza follows the biblical shift from third person to second person, but adds to the images of the shepherd’s rod and staff the suggestion of a processional cross familiar to many nineteen-century Anglican congregations. There is a similar churchy slant in the fifth stanza, where the psalter’s “oil” takes on sacramental tones by being called “unction,” and the usual English translation “cup” becomes a comparably Latinate and ecclesiastical “chalice.” As a result, the reference to God’s “house” in the final line of the sixth stanza does not suggest the Temple in Jerusalem so much as it does the church building in which the hymn is being sung.” (ReformedWorship.org)

I doubt that in the last line “Thy house” is simply the church building; heaven is clearly meant and specified by the “forever.” Anglocatholic services are long, but not that long.

1 The King of love my shepherd is,

whose goodness faileth never.

I nothing lack if I am his,

and he is mine forever.

2 Where streams of living water flow,

my ransomed soul he leadeth;

and where the verdant pastures grow,

with food celestial feedeth.

3 Perverse and foolish, oft I strayed,

but yet in love he sought me;

and on his shoulder gently laid,

and home, rejoicing, brought me.

4 In death’s dark vale I fear no ill,

with thee, dear Lord, beside me;

thy rod and staff my comfort still,

thy cross before to guide me.

5 Thou spreadst a table in my sight;

thy unction grace bestoweth;

and oh, what transport of delight

from thy pure chalice floweth!

6 And so through all the length of days,

thy goodness faileth never;

Good Shepherd, may I sing thy praise

within thy house forever.

Here is the Cardiff Festival Choir singing the hymn. Here is John Rutter’s lovely arrangement with harp accompaniment.

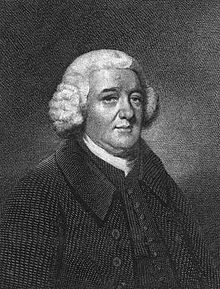

Henry Williams Baker

Sir Henry Williams Baker was the eldest son of Admiral Sir Henry Loraine Baker. Henry was born in London, May 27, 1821, and educated at Trinity College, Cambridge, where he graduated, B.A. 1844, M.A. 1847. Taking Holy Orders in 1844, he became, in 1851, Vicar of Monkland, Herefordshire. This benefice he held to his death, on Monday, Feb. 12, 1877. He succeeded to the Baronetcy in 1851. His hymns, including metrical litanies and translations, number in the revised edition of Hymns Ancient & Modern, 33 in all.. The last audible words which lingered on his dying lips were the third stanza of his rendering of the 23rd Psalm, “The King of Love, my Shepherd is:”—

Perverse and foolish, oft I strayed,

but yet in love he sought me;

and on his shoulder gently laid,

and home, rejoicing, brought me.

This tender sadness, brightened by a soft calm peace, was an epitome of his poetical life.

The tune is St. Columba. Because the compilers of the 1906 English Hymnal were denied permission to use Dykes’s original tune (see sidebar, below), musical editor Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958) turned to a folk tune that his former teacher Charles Villiers Stanford (1852-1924) had recently edited for a collection of Irish music (A Complete Collection of Irish Music as noted by George Petri (London, 1902-1905); ST. COLUMBA is no. 1043). The two most notable improvements Vaughan Williams made in the hymn tune known as ST. COLUMBA were the lengthening of the second and fourth lines to extend the Common Meter tune to 8787 in order to accommodate Baker’s text—this being their first appearance together—and the use of a triplet (rather than an eighth and two sixteenths) in the sixth measure. (ReformedWorship.org).

The words of this hymn are often subjected ot “modernization,” a process that frequently obscures the meaning the poet intended. For example, a 1994 Lutheran hymnal changes

Thou spreadst a table in my sight;

thy unction grace bestoweth;

and oh, what transport of delight

from thy pure chalice floweth!

to

You spread a table in my sight,

A banquet here bestowing;

Your oil of welcome, my delight;

My cup is overflowing!

The clear allusion to the Eucharistic chalice has been almost completely obscures, and the deep emotion of “transports of delight” toned down and transferred to oil, which might be a reference to the oil used at baptism, if Lutherans use, it, but it is very obscure.

On a personal note, I have used the hymn at the funeral masses I have arranged for member of my family: my mother, my nephew, my sister. I think the hymn combines the sweetness, sadness, and tender trust that we feel when a fellow Christian leaves this life to enter into the presence of the Lord.

We mourn, not as those who have no hope, but we do and should mourn.

When I was walking the Camino de Santiago in 2010, I passed through a pastoral landscape in which shepherds with their staffs were leading flocks of sheep. I sang this hymn, with especial stress on the stanza,

Perverse and foolish, oft I strayed,

but yet in love he sought me;

and on his shoulder gently laid,

and home, rejoicing, brought me.

On the Camino I had the strong feeling that I was on my way Home; if I could not walk, I would be carried.

_____________________

Be joyful Mary, heavenly Queen is a translation of Regina coeli, iubila, an anonymous 17th century hymn. The tune was written by Johann Leisentritt (1527-1586), and published in his Catholicum Hymnologium Germanicum in 1584. Here is Notre Dame.

The words in the 1901 translation (Psallite: English Catholic Hymns) closely follow the Regina coeli. The words have been modernized in out version. I am searching for the original translation.

1 Be joyful, Mary, heav’nly Queen,

Gaude, Maria!

Your grief is changed to joy serene,

Alleluia! Laetare, O Maria!2 The Son you bore by heaven’s grace,

Gaude, Maria!

Did by his death our guilt erase,

Alleluia! Laetare, O Maria!

3 The Lord has risen from the dead,

be joyful, Mary!Gaude, Maria!

He rose in glory as he said,

Alleluia! Laetare, O Maria!4 Then pray to God, O Virgin fair,

be joyful, Mary!Gaude, Maria!

That he our souls to heaven bear,

Alleluia! Laetare, O Maria!

Here is the Notre Dame choir singing it as a recessional.

The Latin original is somewhat different:

Regina coeli jubila, Gaude Maria.

Jam pulsa cedunt nubila.

Alleluia. Laetare o Maria.2. Quem digna terris gignere, Gaude Maria.

Vivis resurgit funere.

Alleluia. Laetare o Maria.3. Sunt fracta mortis spicula, Gaude Maria.

Jesu jacet mors subdita.

Alleluia. Laetare o Maria.4. Acerbitas solatium, Gaude Maria.

Luctus redonat gaudium.

Alleluia. Laetare o Maria.5. Turbata sputis lumina, Gaude Maria.

Phoebea vincunt fulgura,

Alleluia. Laetare o Maria.6. Manum pedumque vulnera, Gaude Maria.

Sunt gratiarum flumina,

Alleluia. Laetare o Maria.7. Transversa ligni robora, Gaude Maria.

Sunt sceptra regni fulgida.

Alleluia. Laetare o Maria.8. Lucet arundo purpura, Gaude Maria.

Ut fulva terrae viscera,

Alleluia. Laetare o Maria..9. Catena, clavi, lancea, Gaude Maria.

Triumphi sunt insignia,

Alleluia. Laetare o Maria..10. Ergo, Maria, plaudito, Gaude Maria.

Clientibus succurrito,

Alleluia. Laetare o Maria.

Here is Praetorius’s setting.

___________________

I know that me redeemer lives is by the English Baptist Samuel Medley (1738-1799). The hymn uses a simple repetition of “He lives” to celebrate the resurrected Jesus who rules our lives and gives us eternal life. Christ is risen! Truly He is risen!

This is the earliest version I could find (1816):

1 I know that my Redeemer lives,

What comfort this sweet sentence gives!

He lives, he lives, who once was dead,

He lives, my everlasting Head.2 He lives, triumphant from the grace,

He lives, eternally to save;

He lives, all-glorious in the sky,

He lives, exulted there on high.3 He lives to bless me with his love,

He lives to plead for me above,

He lives my hungry soul to feed,

He lives to help in time of need.4 He lives and grants me rich supply,

He lives to guide me with his eye,

He lives to comfort me when faint,

He lives to hear my soul’s complaint.5 He lives to crush the pow’rs of hell,

He lives that he may in me dwell,

He lives to heal and make me whole

He lives to guard my feeble soul.6 He lives to silence all my fears;

He lives to stop and wipe my tears,

He lives to calm my troubled heart,

he lives all blessings to impart.7 He lives my kind, my heavenly friend,

He lives and loves me to the end;

He lives, and while he lives I’ll sing,

He lives my Prophet, Priest and King.8 He lives and grants me daily breath,

He lives, and I shall conquer death,

He lives my mansion to prepare,

He lives to bring me safely there.9 He lives all glory to his name,

He lives, my Jesus still the same;

O the sweet joy this sentence gives,

I know that my Redeemer lives.

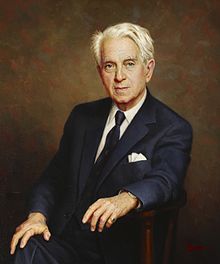

Samuel Medley

Samuel Medley came from a devout family but led a dissolute life as a youth and joined the Royal Navy. In 1759 Medley’s ship engaged in a naval battle with a French ship, during which Medley’s leg was severely injured. After the battle, Medley’s leg continued to grow worse, even to the point of having to amputate the leg to save Medley’s life. One evening, the physician aboard the ship told Medley that if his leg did not improve by morning, they would have to amputate or he could face death. During the night, Medley remembered what his grandfather had taught him when he was younger, and he began to pray vigorously that his leg might be spared. The next morning, to the surprise of all on the ship, the physician examined the leg and determined that it had healed so well that amputation was no longer needed. Immediately afterwards, Medley returned to his room, found the bible his grandfather had given him, and began reading. When Medley’s ship returned to England, he was sent to his grandfather’s house to recover. There Medley’s grandfather read a sermon written by Isaac Watts, which moved Medley greatly; he immediately converted and became a Christian. After his conversion, Medley began attending the Baptist Church in Eagle Street, London, then under the care of Dr. Gifford, and shortly afterwards opened a school, which for several years he conducted with great success. Having begun to preach, he received, in 1767, a call to become pastor of the Baptist church at Watford. Thence, in 1772, he removed to Byrom Street, Liverpool, where he gathered a large congregation, and for 27 years was remarkably popular and useful. After a long and painful illness he died July 17, 1799.

First published anonymously in Henry Boyd’s Select Collection of Psalm and Hymn Tunes (1793), DUKE STREET was credited to John Hatton (b. Warrington, England, c. 1710; d, St. Helen’s, Lancaster, England, 1793) in William Dixon’s Euphonia (1805). Virtually nothing is known about Hatton, its composer, other than that he lived on Duke Street in St. Helen’s and that his funeral was conducted at the Presbyterian chapel there.

Here is King of Glory Lutheran Church singing it.

DUKE STREET was also used in Charles Ives’ Thanksgiving and Forefathers’ Day (around 4:00)

____________________________

Anthems

Psalm 23, The Lord is my shepherd, Herbert Howells

Herbert Howells (1892—1983) was best known as a composer of Anglican church music. Psalm 23 is from his Requiem.

In September 1935 Howells’ placid existence was abruptly shattered when his nine-year-old son Michael contracted polio during a family holiday and died in London three days later. Howells was deeply affected and continued to commemorate the event until the end of his life. Much of Howells’ subsequent music shows the influence of this loss. He began the Requiem in 1932, but more and more associated his work on it with Michael’s death.

Michael’s grave at Twigworth

Howells’ music is much more complex than other choral music of the period, most of which still followed in the Austro-German tradition that had dominated English music for two centuries. Long, unfolding melodies are seamlessly woven into the overall textures; the harmonic language is modal, chromatic, often dissonant and deliberately ambiguous. The overall style is free-flowing, impassioned and impressionistic, all of which gives Howells’ music a distinctive visionary quality.

Here is the Imperial College Chamber Choir singing Psalm 23.

____________________

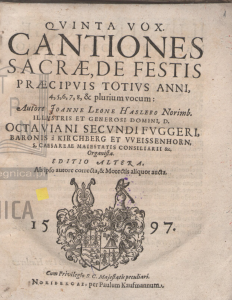

Ego sum resurrectio, Hans Leo Hassler

Ego sum resurrectio et vita. Qui credit in me

etiam si mortuus fuerit, vivet.

Et omnis qui vivit et credit in me, non morietur in aeternum.

I am the resurrection and the life: he that believeth in me,

although he be dead, shall live:

And every one that liveth and believeth in me shall not die for ever.

This motet is No. 11 in Hassler’s Cantiones sacrae de festis praecipuis totius anni. . . , published at Augsburg in 1591.

Hans Leo Hassler

Hans Leo Hassler (1564- 1612) was the first German composer of the Renaissance who went to Italy to continue studies; he studied in Venive inder Andrea Gabrieli, Giovanni’s uncle, He returned to Germany, where he was an expert organist as well as a composer. Hassler’s influence was one of the reasons for the Italian domination over German music and for the common trend of German musicians finishing their education in Italy. Though Hassler was Protestant, he wrote many masses and directed the music for Catholic services in Augsburg.

While in the service of Octavian Fugger, Hassler dedicated both his Cantiones sacrae and a book of masses for four to eight voices to him. Due to the demands of the Catholic patrons, and his own Protestant beliefs, Hassler’s compositions represented a skillful blend of both religions’ music styles that allowed his compositions to function in both contexts Hassler sought to blend the Italian virtuoso style with the traditional style prevalent in Germany. This was accomplished in the chorale motet by employing the thorough bass continuo and including instrumental and solo ornamentation.

We used one of Hassler’s masses at our wedding in St. Matthew’s cathedral in Washington.