Mount Calvary Church

A Roman Catholic Congregation of

The Personal Ordinariate of the Chair of St. Peter

Anglican Use

Trinity XI

Hymns

Glorious things of thee are spoken

Jerusalem, my happy home

The church’s one foundation

Common: Missa de Angelis

________________________

The hymns today focus upon the Church, which is built on the rock of Peter.

Glorious things of thee are spoken was written by John Newton (1725—1807), sometime slave trader and author of Amazing Grace, with the help of William Cowper (1731—1800). The opening line quotes Psalm 87:3 “Glorious things of you are spoken, O city of God.” The theme is the universal church. The text begins with a vision of the new city of God (Heb 12:22), founded on the rock of ages (2 Sam 22), from which flow streams of living waters (Rev 22), alluding to the rock that Moses truck in the desert, to the Gihon spring on Mount Zion, and to the living water that Jesus promised the women at the well. The third stanza names the cloud and fire — the enduring presence God in the church —, and the manna (Ex 13:21, 16:31), a symbol of the Eucharist. We are washed in the Blood of the Lamb, making us Kings and priests to our God, to Whom we offer in Jesus the sacrifice of our lives in praise and thanksgiving for the salvation He has wrought.

The tune, AUSTRIA, by Haydn, created problems for England during World War II and was replaced by a newly composed tune, but we are using the 18th century melody, which also appears in the Emperor quartet, opus 70, no. 5.

Here is the Robert Shaw Chorale.

Glorious things of thee are spoken,

Sion, city of our God;

He whose word cannot be broken,

Formed thee for his own abode;

On the Rock of Ages founded,

What can shake thy sure repose?

With salvation’s walls surrounded,

Thou may’st smile at all thy foes.See, the streams of living waters

Springing from eternal love,

Well supply thy sons and daughters,

And all fear of want remove.

Who can faint, when such a river

Ever will their thirst assuage?

Grace which, like the Lord, the giver,

Never fails from age to age.Round each habitation hovering,

See the cloud and fire appear

For a glory and a covering,

Showing that the Lord is near.

Thus deriving from their banner,

Light by night, and shade by day,

Safe they feed upon the manna,

Which he gives them when they pray.Blest inhabitants of Sion,

Washed in the Redeemer’s blood!

Jesus, whom their souls rely on,

Makes them kings and priests to God.

‘Tis his love his people raises

Over self to reign as kings:

And as priests, his solemn praises

Each for a thank-offering brings.

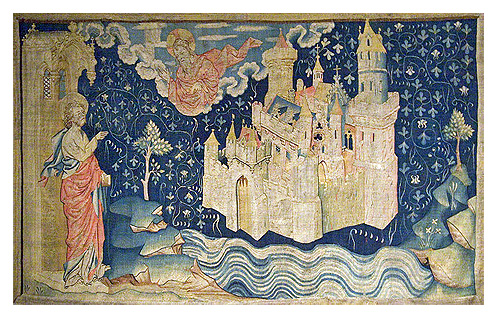

Jerusalem my happy home has a complicated history. It may have been written by a 16th century Catholic priest “F. B. P” (¿Francis Baker Porter?) imprisoned in the Tower and it may be based on The Meditations of St. Augustine. It exists in several versions; the one we use was said to be the favorite hymn of Elizabeth Ann Seton.

As adults, we know we live in a vale of tears: the disappointments of life, the sickness and death of friends and family, the destruction that evil works in God’s creation. This world as it now exists is not our home, which we will find in the transfigured world of the New Creation. The disharmony of the present age will be replaced by the harmony of heaven, symbolized by music, the new song, canticum novum, that we will forever sing. As the Navajos say, Hózhó Nahasdlii: It is finished in beauty. St. Mary Magdalen was remembered as a penitent; but penitence leads to the joy of heaven.

LAND OF REST is an American folk tune with roots in the ballads of northern England and Scotland. It was known throughout the Appalachians; a shape-note version of the tune was published in The Sacred Harp (1844).

Here is St Peter’s in the Loop; here St. Clement’s, Philadelphia; here St Mark’s Cathedral, Seattle; here is a prelude on the tune.

Here is the complete text, with the stanzas in the 1940 Hymnal marked in red.

Jerusalem, my happy home,

when shall I come to thee?

When shall my sorrows have an end?

Thy joys when shall I see?O happy harbor of the saints!

O sweet and pleasant soil!

In thee no sorrow may be found,

no grief, no care, no toil.In thee no sickness may be seen,

no hurt, no ache, no sore;

there is no death nor ugly devil,

there is life for evermore.No dampish mist is seen in thee,

no cold nor darksome night;

there every soul shines as the sun;

for God himself gives light.There lust and lucre cannot dwell;

there envy bears no sway;

there is no hunger, heat, nor cold,

but pleasure every way.Jerusalem, Jerusalem,

God grant that I may see

thine endless joy, and of the same

partaker ay may be!Thy walls are made of precious stones,

thy bulwarks diamonds square;

thy gates are of right orient pearl;

exceeding rich and rare;thy turrets and thy pinnacles

with carbuncles do shine;

thy very streets are paved with gold,

surpassing clear and fine;thy houses are of ivory,

thy windows crystal clear;

thy tiles are made of beaten gold–

O God that I were there!Within thy gates nothing doth come

that is not passing clean,

no spider’s web, no dirt, no dust,

no filth may there be seen.Aye, my sweet home, Jerusalem,

would God I were in thee:

would God my woes were at an end,

thy joys that I might see.Thy saints are crowned with glory great;

they see God face to face;

they triumph still, they still rejoice

most happy is their case..We that are here in banishment

continually do mourn:

we sigh and sob, we weep and wail,

perpetually we groan.Our sweet is mixed with bitter gall,

our pleasure is but pain:

our joys scarce last the looking on,

our sorrows still remain.But there they live in such delight,

such pleasure and such play,

as that to them a thousand years

doth seem as yesterday.Thy vineyards and thy orchards are

most beautiful and fair,

full furnished with trees and fruits,

most wonderful and rare.Thy gardens and thy gallant walks

continually are green:

there grow such sweet and pleasant flowers

as nowhere else are seen.There is nectar and ambrosia made,

there is musk and civet sweet;

there many a fair and dainty drug

is trodden under feet.There cinnamon, there sugar grows,

there nard and balm abound.

What tongue can tell or heart conceive

the joys that there are found?Quite through the streets with silver sound

the flood of life doth flow,

upon whose banks on every side

the wood of life doth grow.There trees for evermore bear fruit,

and evermore do spring;

there evermore the angels be,

and evermore do sing.There David stands with harp in hand

as master of the choir:

ten thousand times that man were blessed

that might this music hear.Our Lady sings Magnificat

with tune surpassing sweet,

and all the virgins bear their part,

sitting at her feet.There Magdalen hath left her moan,

and cheerfully doth sing

with blessèd saints, whose harmony

in every street doth ring.Jerusalem, my happy home,

would God I were in thee!

Would God my woes were at an end

thy joys that I might see!

The Church’s one foundation was written by Samuel John Stone (1839—1900). He wrote this hymn as one of twelve published in Lyra Fidelium: Twelve Hymns on the Twelve Articles of the Apostles’ Creed (1866). It is an expansion of the article of the Apostles’ Creed: “the holy Catholic church, the communion of saints.” Stone counters Bishop John Colenso’s (1814—1883) attack on the infallibility of Scripture and on the unity of the human race: Colenso thought that different races descended from different first parents.

Stone fills the hymn with Scriptural images: the church is the Bride of Christ, created by water (baptism) and the word (Scripture). Stone emphasizes the unity of the Church, the redeemed human race: “over all the earth,” “one Lord, one faith, one birth,” “one holy Name,” “one food” (the Eucharist), “one hope.” In Stone’s time and now the Church is divided by schisms and heresies (Colenso approved of multiple marriages, i.e., polygamy). Christians are slaughtered daily throughout the world, sometimes at the very altar. John in Revelation “saw under the altar the souls of those who had been slaughtered for the word of God and for the testimony they had given; they cried out with a loud voice, ‘Sovereign Lord, holy and true, how long will it be before you judge and avenge our blood on the inhabitants of the earth?’” The Church is militant against evil and therefore attacked by Satan, yet even now we experience the communion of the saints, the communion founded in the Trinity, Whose life of love we enter through the Eucharist.

Here is King’s College, Cambridge; here a vigorous rendition.

1 The church’s one foundation

is Jesus Christ her Lord;

she is his new creation

by water and the word:

from heaven he came and sought her

to be his holy Bride;

with his own blood he bought her,

and for her life he died.

2 Elect from every nation,

yet one o’er all the earth,

her charter of salvation

one Lord, one faith, one birth;

one holy name she blesses,

partakes one holy food,

and to one hope she presses

with every grace endued.

3 Though with a scornful wonder

men see her sore opprest,

by schisms rent asunder,

by heresies distrest;

yet saints their watch are keeping,

their cry goes up, ‘How long?’

And soon the night of weeping

shall be the morn of song.

4 ‘Mid toil and tribulation,

and tumult of her war,

she waits the consummation

of peace for evermore;

till with the vision glorious

her longing eyes are blest,

and the great church victorious

shall be the church at rest.

5 Yet she on earth hath union

with God the Three in One,

and mystic sweet communion

with those whose rest is won:

O happy ones and holy!

Lord, give us grace that we,

like them, the meek and lowly,

on high may dwell with thee.

S. J. Stone

Samuel John Stone, a clergyman of the Church of England, the son of Rev. William Stone, was born at Whitmore, Staffordshire, April 25, 1839. He was educated at Pembroke College, Oxford, where he was graduated B.A. in 1862. Later he took orders and served various Churches. He succeeded his father at St. Paul’s, Haggerstown, in 1874. He was the author of many original hymns and translations, which were collected and published in 1886. He died November 19, 1900.

Stone wrote The church’s one foundation as his response to the Colenso controversy.

In 1862 Bishop J.W. Colenso caused a great controversy with The Pentateuch and the Book of Joshua Critically Examined when he tried to remove points of doctrine which men of the mid-nineteenth century found impossible to believe. For him the entire problem centered on the right of the minister to free thought, a right which, as he wrote in a later volume, was denied by a law which bound each minister “by law to believe in the historical truth of Noah’s Flood, as recorded in the Bible, which the Church believed in some centuries ago, before God had given us the light of modern science.” The blows of the geologist’s hammer were here decisive.

“My own knowledge of some branches of science, of Geology in particular, had been much increased since I left England; and I now knew for certain, on geological grounds, a fact, of which I had only had misgivings before, viz., that a Universal Deluge, such as the Bible manifestly speaks of, could not possibly have taken place in the way described in the Book of Genesis, not to mention other difficulties which the story contains. I refer especially to the circumstance, well known to all geologists, . . . that volcanic hills exist of immense extent in Auvergne and Languedoc, which must have been formed ages before the Noachian Deluge, and which are covered with light and loose substances, pumice-stone &c., that must have been swept away by a Flood, but do not exhibit the slightest sign of having ever been so disturbed.”

Once the Bishop’s doubts had been aroused by the facts of geology and further stimulated by the questions of native assistants who were aiding his translation of the Bible, he proceeded to examine “the other difficulties the story contains.”

After investigating the details, as presented in Exodus, of camp life, of sacrifice, of numbers of men and animals — details all of which, according to contemporary ecclesiastic law, had to be literally true — Bishop Colenso was led to the conviction, painful, he said, both to himself and his reader, that

“the Pentateuch, as a whole, cannot personally have been written by Moses, or by anyone acquainted personally with the facts which it professes to describe, and, further, that the (so-called) Mosaic narrative, by whomsoever written, and though imparting to us, as I fully believe it does, revelations of the Divine Will and Character, cannot be regarded as historically true.”

To feel the force of these words and to understand the anguish they both caused and relieved, it is necessary to realize how widespread was the view, quoted by Colenso, that “The Bible cannot be less that verbally inspired. Every word, every syllable, every letter, is just what it would be, had God spoken from heaven without any human intervention.” In the introductory remarks to the first part of his work, Colenso quotes from Burgon’s Inspiration and Interpretation, a standard work for ministerial students:

“The BIBLE is none other than the Voice of Him that sitteth upon the Throne! Every book of it — every chapter of it — every verse of it — every word of it — every syllable of it — (where are we to stop?) every letter of it — is the direct utterance of the Most High! The Bible is none other than the word of God — not some part of it more, some part of it less, but all alike, the utterance of Him, who sitteth upon the Throne — absolute — faultless — unerring — supreme.”

(Victorian Web)

Colenso, to do him justice, could not believe in the fundamentalist approach to the Bible, which regrads it as Muslims regard the Koran: very letter divinely inspired and literally true (as undersold by a Westerner). But Colenso also discarded teachings essential to Christianity, such as the unity of the human race”

Colenso was a polygenist; he believed in CoAdamism that races had been created separately. Colenso pointed to monuments and artifacts in Egypt to debunk monogenist beliefs that all races came from the same stock. Ancient Egyptian representations of races for example showed exactly how the races looked today. Egyptological evidence indicated the existence of remarkable permanent differences in the shape of the skull, bodily form, colour and physiognomy between different races which are difficult to reconcile with biblical monogenesis. Colenso believed that racial variation between races was so great, that there was no way all the races could have come from the same stock just a few thousand years ago, he was unconvinced that the climate could change racial variation, he also with other biblical polygenists believed that monogenists had interpreted the bible wrongly.[16] Colenso said “It seems most probable that the human race, as it now exists, had really sprung from more than one pair”. Colenso denied that polygenism caused any kind of racist attitudes or practices, like many other polygenists he claimed that monogenesis was the cause of slavery and racism. Colenso claimed that each race had sprung from a different pair of parents, and that all races had been created equal by God. (wikipedia)

Stone also tried a different approach to critiquing the heresies of his time:

The Soliloquy of a Rationalistic Chicken:

On the Picture of a Newly Hatched Chicken Contemplating the Fragments of Its Native Shell

Most strange!

Most queer,—although most excellent a change!

Shades of the prison-house, ye disappear!

My fettered thoughts have won a wider range,

And, like my legs, are free;

No longer huddled up so pitiably:

Free now to pry and probe, and peep and peer,

And make these mysteries out.

Shall a free-thinking chicken live in doubt?

For now in doubt undoubtedly I am:

This problem’s very heavy on my mind,

And I’m not one to either shirk or sham:

I won’t be blinded, and I won’t be blind!

Now, let me see;

First, I would know how did I get in there?

Then, where was I of yore?

Besides, why didn’t I get out before?

Bless me!

Here are three puzzles (out of plenty more)

Enough to give me pip upon the brain!

But let me think again.

How do I know I ever was inside?

Now I reflect, it is, I do maintain,

Less than my reason, and beneath my pride

To think that I could dwell

In such a paltry miserable cell

As that old shell.

Of course I couldn’t! How could I have lain,

Body and beak and feathers, legs and wings,

And my deep heart’s sublime imaginings,

In there?

I meet the notion with profound disdain;

It’s quite incredible; since I declare

(And I’m a chicken that you can’t deceive)

What I can’t understand I won’t believe.

Where did I come from, then? Ah! where, indeed?

This is a riddle monstrous hard to read.

I have it! Why, of course,

All things are moulded by some plastic force

Out of some atoms somewhere up in space,

Fortuitously concurrent anyhow:—

There, now!

That’s plain as is the beak upon my face.

What’s that I hear?

My mother cackling at me! Just her way,

So prejudiced and ignorant I say;

So far behind the wisdom of the day!

What’s old I can’t revere.

Hark at her. “You’re a little fool, my dear,

That’s quite as plain, alack!

As is the piece of shell upon your back!”

How bigoted! upon my back, indeed!

I don’t believe it’s there;

For I can’t see it; and I do declare,

For all her fond deceivin’,

What I can’t see I never will believe in!