Jim Breese

James Lawrence Breese, Jr., (1884-1959) my wife’s eighth cousin twice removed, was the son of James Lawrence Breese and Francis Tileston Potter. He was Princeton ’09. He married Marjorie Howard Gorges (1894-1974); they had four children, Anne, Frances Potter (1916-1998), Mary NC, (1919-199), and James Lawrence (1927-2009).

Marjorie Howard Gorges

James was a classmate of Franklin Delano Roosevelt at Groton. Roosevelt was the Assistant Navy Secretary, which helped get James on the historic flight. In 1919 he was engineering officer and co-pilot in the NC4, the plane which made the first transatlantic flight from New York to Lisbon (Lindbergh made the first solo flight).

Lt. James Breese

The transatlantic capability of the NC-4 was the result of developments in aviation that began before World War I. In 1908, Glenn Curtiss had experimented unsuccessfully with floats on the airframe of an early June Bug craft, but his first successful takeoff from water was not carried out until 1911, with an A-1 airplane fitted with a central pontoon. In January 1912, he first flew his first hulled “hydro-aeroplane”, which led to an introduction with the retired English naval officer John Cyril Porte who was looking for a partner to produce an aircraft with him to attempt win the prize of the newspaper the Daily Mail for the first transatlantic flight between the British Isles and North America – not necessarily nonstop, but using just one airplane. (e.g. changing airplanes in Iceland or the Azores was not allowed.)

Emmitt Clayton Bedell, a chief designer for Curtiss, improved the hull by incorporating the Bedell Step, the innovative hydroplane “step” in the hull allowed for

breaking clear of the water at takeoff. Porte and Curtiss were joined by Lt. John H. Towers of the U.S. Navy as a test pilot. This Curtiss Model H America flying boat of 1914 was a larger aircraft with two engines and two pusher propellers. The members of the team hoped to claim the prize for a transatlantic flight

Development of this project ceased with the outbreak of World War I in Europe later that year. Porte, now back in the Royal Navy‘s flight arm the RNAS, commissioned more flying boats to be built by the Curtiss Company. These could be used for long-range antisubmarine warfare patrols. Porte modified these aircraft, and he developed them into his own set of Felixstowe flying boats with more powerful engines, longer ranges, better hulls and better handling characteristics. He shared this design with the Curtiss Company, which built these improved models under license, selling them to the U.S. Government.

This culminated in a set of four identical aircraft, the NC-1, NC-2, NC-3 and the NC-4, the U.S. Navy‘s first series of four medium-sized Curtiss NC floatplanes made for the Navy by the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company. The NC-4 made its first test flight on 30 April 1919.[2]

World War I had ended in November 1918, before the completion of the four Curtiss NCs. Then in 1919, with several of the new floatplanes in its possession, the officers in charge of the U.S. Navy decided to demonstrate the capability of the seaplanes with a transatlantic flight. However it was necessary to schedule refueling and repair stops that were also for crewmen’s meals and sleep and rest breaks — since these Curtiss NCs were quite slow in flight. For example, the flight between Newfoundland and the Azores required many hours of night flight because it could not be completed in one day.

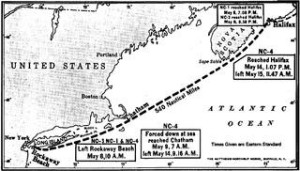

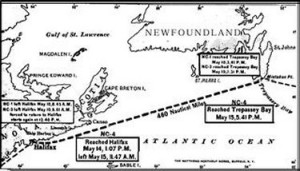

The U.S. Navy’s transatlantic flight expedition began on 8 May 1919. The NC-4 started out in the company of two other Curtiss NCs, the NC-1 and the NC-3 (with the NC-2 having been cannibalized for spare parts to repair the NC-1 before this group of planes had even left New York City). The three aircraft left from Naval Air Station Rockaway, with intermediate stops at the Chatham Naval Air Station, Massachusetts, and Halifax, Nova Scotia, before flying on to Trepassey, Newfoundland, on 15 May. Eight U.S. Navy warships were stationed along the northern East Coast of the United States and Atlantic Canada to help the Curtiss NCs in navigation and to rescue their crewmen in case of any emergency.[3]

The “base ship”, or the flagship for all of the Navy ships that had been assigned to support the flight of the Curtiss NCs, was the former minelayer USS Aroostook (CM-3), which the Navy had converted into a seaplane tender just before the flight of the Curtiss NCs. With a displacement of just over 3,000 tons, the Aroostook was larger than the Navy’s destroyers that had been assigned to support the transatlantic flight in 1919. Before the Curtiss NCs took off from New York City, the Aroostook had been sent to Trepassey, Newfoundland, to await their arrival there, and then provide refueling, relubrication, and maintenance work on the NC-1, NC-3 and NC-4. Next, she steamed across the Atlantic meet the group when they arrived in England.

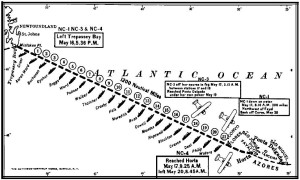

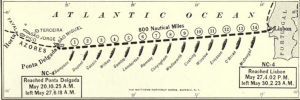

On 16 May, the three Curtiss NCs departed on the longest leg of their journey, from Newfoundland to the Azores Islands in the mid-Atlantic. Twenty-two more Navy ships, mostly destroyers, were stationed at about 50-mile (80 km) spacings along this route.[4] These “station ships” were brightly illuminated during the nighttime. Their sailors blazed their searchlights into the sky, and they also fired bright star shells into the sky to help the aviators to stay on their planned flight path.[5]

After flying all through the night and most of the next day, the NC-4 reached the town of Horta on Faial Island in the Azores on the following afternoon, having flown about 1,200 miles (1,920 km). It had taken the crewmen 15 hours, 18 minutes, to fly this leg. The NCs encountered thick fog banks along the route. Both the NC-1 and the NC-3 were forced to land on the open Atlantic Ocean because the poor visibility and loss of a visual horizon made flying extremely dangerous. NC-1 was damaged landing in the rough seas and could not become airborne again. NC-3 had mechanical problems.

The crewmen of the NC-1, including future Admiral Marc Mitscher, were rescued by the Greek cargo ship SS Ionia. This ship took the NC-1 in tow, but it sank three days later and was lost in deep water.

The pilots of the NC-3, including future Admiral Jack Towers, taxied their floatplane some 200 nautical miles to reach the Azores, where it was taken in tow by a U.S. Navy ship.

US Navy warships “strung out like a string of pearls” along the NC’s flight path (3rd leg)

Three days after arriving in the Azores, on 20 May, the NC-4 took off again bound for Lisbon, but it suffered mechanical problems, and its pilots had to land again at Ponta Delgada, São Miguel Island, Azores, having flown only about 150 miles (240 km). After several days of delays for spare parts and repairs, the NC-4 took off again on 27 May. Once again there were station ships of the Navy to help with navigation, especially at night. There were 13 warships arranged along the route between the Azores and Lisbon.[4] The NC-4 had no more serious problems, and it landed in Lisbon harbor after a flight of nine hours, 43 minutes. Thus, the NC-4 become the first aircraft of any kind to fly across the Atlantic Ocean – or any of the other oceans. By flying from Massachusetts and Halifax to Lisbon, the NC-4 also flew from mainland-to-mainland of North America and Europe. Note: the seaplanes were hauled ashore for maintenance work on their engines.

The part of this flight just from Newfoundland to Lisbon had taken a total time 10 days and 22 hours, but with the actual flight time totaling just 26 hours and 46 minutes.

Jim is second from left

NC4 award

James named a daughter Mary NC.

His father had gotten James interested in automobiles After leaving the military, James took a job in a company that tried to build steam cars. One was built, but it was too expensive. However, in this model there was an oil burner with automatic controls to heat a boiler for steam power.

James said he studied the candle flame to see how a flame could be the right temperature to vaporize enough grease to power the flame without creating smoke. He adopted the principle to the oil burner. Jim adopted it to home furnaces; it was the first thermostatically controlled heater.

James first visited Santa Fe when he was flying a tri-motored Ford plane to Winslo, Arizona. Headwinds delayed him and he was running out of gas. Someone remembered that there was a town called Santa Fe nearby. He saw and arrow on a roof and followed it to a landing strip. As he taxied down the runway the engine quit; he had run out of gas. He liked the town and bought property on Upper Canyon Rd., where he built a house.

Jim developed and tested the units in Santa Fe, but the manufacturing was farmed out to factories around the world. By 1954 he had sold three million units, many to the US Army to heat troops during wartime, then throughout the US and Europe.

Breese Burner Factory, Upper Canyon Rd., Santa Fe (later Santa Fe Prep)

Jim in WWII Civil Air Patrol

James and Marjorie were divorced. James married a nurse, Irene Rich (Anna Josefa Irine Sobczyk, 1902-1989) in 1940.

Irene Rich (Anna Josefa Irine Sobcyzk)

Florence Welch Wagner

They were divorced in 1948; he then married the journalist Florence Welch (1883-1971), the widow of Robert Wagner, founder of Rob Wagner’s Script. She had had Ray Bradbury’s early works published and directed a film with Will Rogers. She survived James. He died April 1, 1959 in San Diego.

\

\