After the Reverend Francis Lawrence died, the church continued its mission under new leadership. It had an illustrious literary parishioner: Upton Sinclair.

Sinclair was from a shabby genteel Baltimore family; his father was not very successful. His mother was a devout Episcopalian, so when they moved to New York in 1888 when Upton was ten years old, he became an active parishioner of the Church of the Holy Communion, where the Rev. William Wilmerding Muir continued Lawrence’s work with the poor.

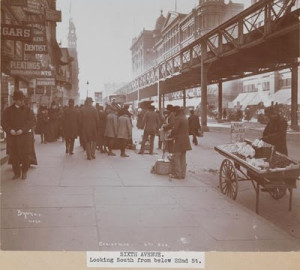

When I was thirteen, I attended service, of my own volition and out of my own enthusiasm, every single day during the forty days of Lent; at the age of fifteen I was teaching Sunday-school. It was the Church of the Holy Communion, at Sixth Avenue and Twentieth Street, New York; and those who know the city will understand that this is a peculiar location—precisely half way between the homes of some of the oldest and most august of the city’s aristocracy, and some of the vilest and most filthy of the city’s slums. The aristocracy were paying for the church, and occupied the best pews; they came, perfectly clad, aus dem Ei gegossen, as the Germans say, with the manner they so carefully cultivate, gracious, yet infinitely aloof. The service was made for them—as all the rest of the world is made for them; the populace was permitted to occupy a fringe of vacant seats.

The assistant clergyman was an Englishman, and a gentleman; orthodox, yet the warmest man’s heart I have ever known. He could not bear to have the church remain entirely the church of the rich; he would go persistently into the homes of the poor, visiting the old slum women in their pitifully neat little kitchens, and luring their children with entertainments and Christmas candy. They were corralled into the Sunday-school, where it was my duty to give them what they needed for the health of their souls.

…….

I had a mind, you see, and I was using it. I was reading the papers, and watching politics and business. I followed the fates of my little slum-boys—and what I saw was that Tammany Hall was getting them. The liquor-dealers and the brothel-keepers, the panders and the pimps, the crap-shooters and the petty thieves—all these were paying the policeman and the politician for a chance to prey upon my boys; and when the boys got into trouble, as they were continually doing, it was the clergyman who consoled them in prison—but it was the Tammany leader who saw the judge and got them out. So these boys got their lesson, even earlier in life than I got mine—that the church was a kind of amiable fake, a pious horn-blowing; while the real thing was Tammany.

I talked about this with the vestrymen and the ladies of Good Society; they were deeply pained, but I noticed that they did nothing practical about it; and gradually, as I went on to investigate, I discovered the reason—that their incomes came from real estate, traction, gas and other interests, which were contributing the main part of the campaign expenses of the corrupt Tammany machine, and of its equally corrupt rival. So it appeared that these immaculate ladies and gentlemen, aus dem Ei gegossen, were themselves engaged, unconsciously, perhaps, but none the less effectively, in spreading the pestilence against which they were blowing their religious horns!

So little by little I saw my beautiful church for what it was and is: a great capitalist interest, an integral and essential part of a gigantic predatory system. I saw that its ethical and cultural and artistic features, however sincerely they might be meant by individual clergymen, were nothing but a bait, a device to lure the poor into the trap of submission to their exploiters.

Sinclair seems to have been an old fashioned Progressive Reformer. He disliked political corruption because it contributed to VICE. As the corrupt political parties received money from businesses from which well-to-do people also contributed, Sinclair held them responsible, although it is not clear what he wanted them to do.

Good Society moved uptown, and the leaders of the Church of the Holy Communion were aware that they were losing the parishioners who supported the church and its work with the poor, so they tried to set up an endowment that would allow the church to function with reduced contributions.

By the 1890s the area was the Ladies’ Mile, with department stores and dry goods stores; but by 1920 they had moved uptown.

The church survived but underwent the vicissitudes which the Episcopal Church also underwent.

“On 14 June 1970 Al Gross’s seventy-fifth birthday was celebrated at an honorary service in Lower Manhattan’s Episcopal Church of the holy Communion. The church, on Sixth Avenue and Twentieth Street, was next door to the offices of the George W. Henry Foundation, which were housed in the church’s parish house. Gross was the executive director of the foundation, an agency founded in 1948 to help young men charged with homosexual offenses. Gross’s career as a homophile activist began in 1937 when he first became associated with Henry. A biographical sketch appeared in the church’s program for the honorary service that charted Gross’s career as a researcher and activist. No mention was made of how and why Gross embarked on his life’s work. Indeed, this was not possible because Gross ws a closeted gay man who began his endeavors after he had been removed as an Episcopal priest. (Henry Minton, Departing from Deviance, p. 95)

The last rector saw the handwriting on the wall and in 1966 had the church designated an historical landmark, which at least protected the exterior.

The church was closed in 1976 and deconsecrated ; it was sold to the Lindisfarne Association, which held poetry readings, lectures, and concerts. The restoration of the building was too expensive for the Association, so the Lindisfarne Association returned the building to the parish and moved to Colorado.

The parish then sold the building to Odyssey House, a drug treatment center. Odyssey House in turn sold to Peter Gatien who open the Limelight night club there in 1983.

Then the trouble started.

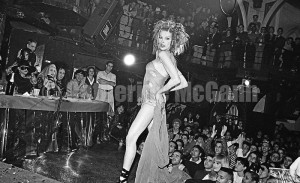

Gatien stripped the beautiful old structure of its sacred context – distorting the Gothic finery with a funhouse mirror, placing bars lined with expensive imported spirits (alcoholic as opposed to celestial) next to the marble crypts, and turning the hushed reverence of the chapel into the riotous frivolity of the VIP lounge.

There were go go cages suspended above the dance floor in the nave.

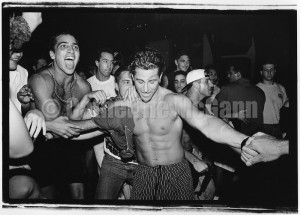

Andy Warhol hosted opening night. Prince came, and Mick Jagger, and Madonna, and the gay nights became every more popular, filling the building to its capacity of 2500.

The NYC Police were unhappy:

The Limelight, located in a former Episcopal church on the Avenue of the Americas at West 20th Street in Chelsea, was temporarily padlocked by the police after a drug raid last year. New York City police arrested three people, including an employee, on charges of selling marijuana. The police said that drugs were rampant at the Limelight and sold in an “open and notorious manner,” sometimes by the employees.

The DEA was not amused:

The owner of three of Manhattan’s largest nightclubs was accused yesterday of turning two of them — the Limelight and the Tunnel — into virtual drug supermarkets, peddling the drug known as Ecstasy to a clientele made up largely of college students and teen-agers.

Zachary W. Carter, the United States Attorney for the Eastern District of New York, said in a written statement that Peter Gatien, one of the reigning nightclub promoters in New York, had “installed a management structure” at the Limelight and the Tunnel that was “designed to ensure successful distribution” of Ecstasy to nightclub patrons, and that the sale of Ecstasy “was the centerpiece of the operation of these clubs, not just a lucrative illegal sideline.”

A former patron remembers fondly:

The amount of sex that went on in the Limelight was unbelievable. Orgies in one room,sex in the bathrooms and on the dance floor, in the video booths. Music and lights were incredible. Nothing exists today to match the Limelight. Late 70’s and 80’s were truly great times. Kids today have no idea what they missed.

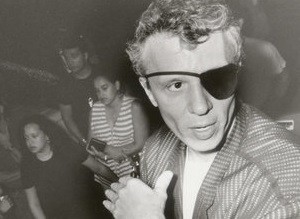

Michael Alig (1966- ) was its most famous employee:

Andre “Angel” Melendez was regular on the New York City club scene and worked at The Limelight. He also sold drugs on the premises. After the bar was closed by federal agents due to an investigation that Peter Gatien was allowing drugs to be sold there, Melendez was fired. Shortly thereafter, he moved into Alig’s apartment. On the night March 17, 1996, Alig and his friend Robert “Freeze” Riggs murdered Melendez after an argument in Alig’s apartment over many things including a long-standing drug debt. Alig has claimed many times that he was so high on drugs that the events are quite cloudy.

After Melendez’s death, Alig and Riggs did not know what to do with the body. They initially left it in the bath tub that they filled with ice. After a few days, the body began to decompose and became odorous. After discussing what to do with Melendez’s body and who should do it, Riggs went to Macy’s to buy knives and a box. In exchange for ten bags of heroin, Alig agreed to dismember Melendez’s body. He cut the legs off, put them in a garbage bag and stuffed the rest into a box. Afterwards, he and Riggs threw the box into the Hudson River.

In the weeks following Melendez’s disappearance, Alig told “anyone who would listen” that he and Riggs had killed him. Most people did not believe Alig and thought his “confession” was a ploy to get attention. Alig was eventually tried and convicted.

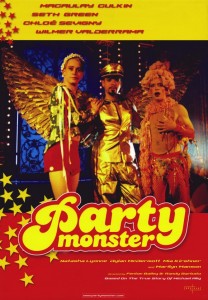

The 2003 film Party Monster featured these events.

The nightclub was the subject of a 2011 movie.

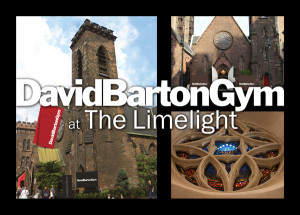

The Limelight was finally shut down. After a brief stint as the Avalon night club (2003-2007), the building became an high-end boutique center, Limelight Marketplace.

This 25,000-square-foot former eighties nightclub (and, before that, a church) was converted into a shopping emporium in May 2010. The 20th Street landmark’s lancet windows, labyrinthine layout, and soaring chapel are the same as they ever were, but the sex-and-drugs-fueled bacchanal is long gone. Where makeout booths and cocaine corners once stood, now you’ll find limited-edition sneakers, handmade belts, MarieBelle chocolates, Hunter boots, tubes of Sue Devitt lip gloss, scented soaps from Caswell-Massey, and Grimaldi’s pizza.

The Marketplace failed, and was replaced by a gym.

Changing demographics often produce superfluous church buildings, and the mission fo the church is not to preserve buildings which are no longer of use to it, even if the buildings are architecturally significant. Creative re-use is a solution, but what the parish failed to do was to put some kind of restrictive covenant one the building that would forbid the premises from being used for inappropriate, immoral, or infamous purposes. Such a restriction would lower the market value but preserve the dignity of a building which, although deconsecrated, had once served as a house of prayer.