Mount Calvary Church

Baltimore

A Roman Catholic Church of

The Personal Ordinariate of the Chair of St. Peter

The Feast of the Transfiguration

August 6, 2017

Hymns

‘Tis good, Lord, to be here

Be Thou my vision

Immortal, invisible, God only wise

Common

Missa de Angelis

_____________________

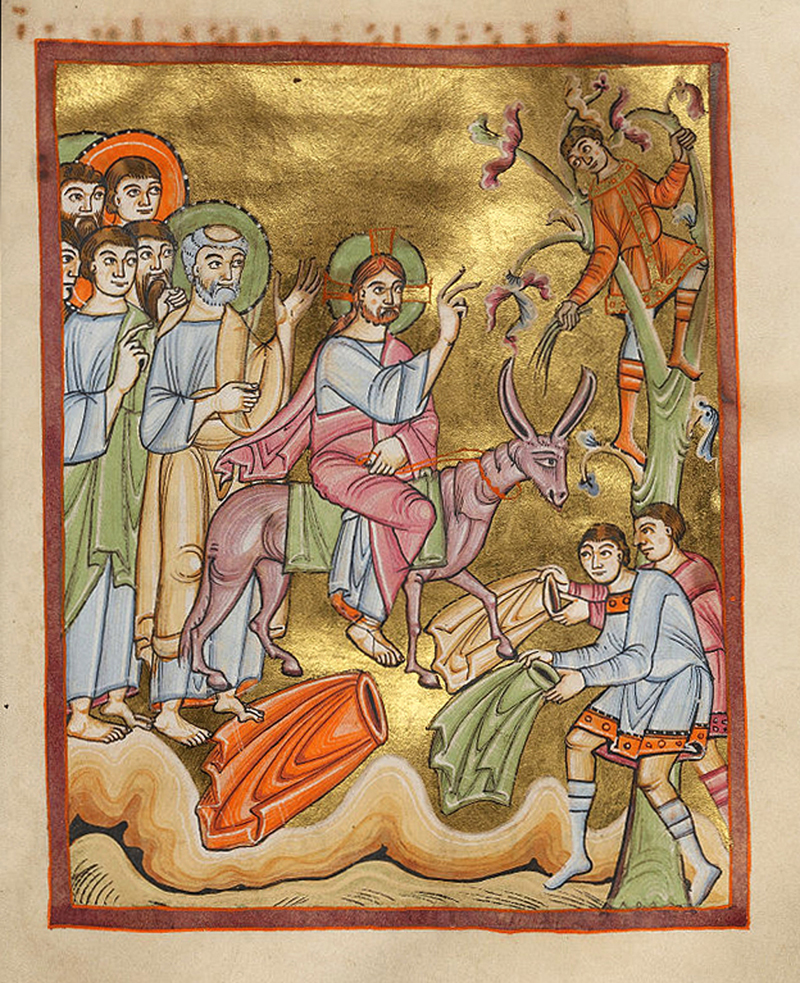

‘Tis good Lord to be here was written by Joseph Armitage Robinson (1858-1933), D.D., Dean of Westminster. Jesus, with Peter, James and John, had to come down from the mountain. The next story in Matthew 17 is of Jesus meeting the crowd and healing an epileptic boy; He predicts His death. In the Liturgy, we catch of glimpse of the Uncreated Light that shone through the humanity of Jesus. It is given to strengthen us in the realities and difficulties of everyday life, where God is to be found.

‘’Tis good, Lord, to be here’, but, Lord, when we go, ‘Come with us to the plain’, be with us in the day to day realities of our life, in our relationships with others, in our family or health problems, in all the joys and sadnesses of everyday life.

‘Tis good, Lord, to be here,

thy glory fills the night;

thy face and garments, like the sun,

shine with unborrowed light.‘Tis good, Lord, to be here,

thy beauty to behold,

where Moses and Elijah stand,

thy messengers of old.Fulfiller of the past,

promise of things to be,

we hail thy body glorified,

and our redemption see.Before we taste of death,

we see thy kingdom come;

we fain would hold the vision bright,

and make this hill our home.‘Tis good, Lord, to be here,

yet we may not remain;

but since thou bidst us leave the mount,

come with us to the plain.

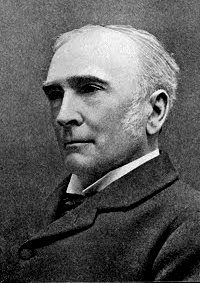

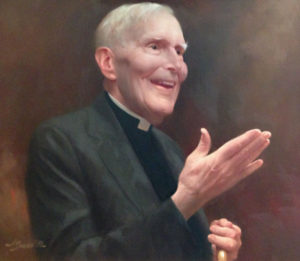

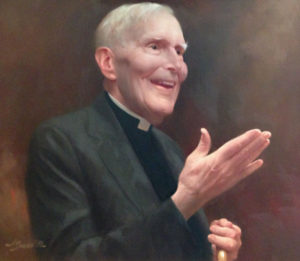

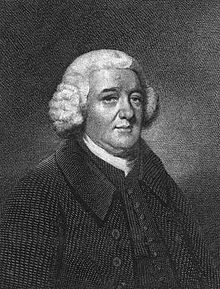

Joseph Armitage Robinson

Joseph Armitage Robinson (1858-1933), D.D., Dean of Westminster and of Wells, of Christ College, Camb. (B.A. 1881, M.A. 1884, D.D. 1896), sometime Fellow of his College, Norrisian Professor of Div., Camb., Rector of St. Margaret’s., Westminster, and Canon of Westminster. As Dean of Wells Robinson enjoyed close links with Downside Abbey. He also critically explored the origins of the Glastonbury legends. Robinson was a participant in the bilateral Anglican-Roman Catholic Maline Conversations. His hymn, “‘Tis good, Lord, to be here” was written c. 1890. It was included in the 1904 edition of Hymns Ancient & Modern.

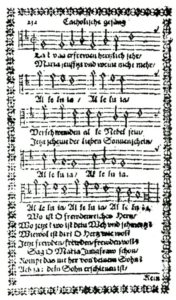

The tune SWABIA was composed by Johann M. Spiess (? – 1772). Spiess taught music at the Gymnasium in Heidelberg, Germany, and played the organ at St. Peter’s Church and (1746-72) at Berne Cathedral.

_____________________________

Be thou my vision. The Irish monk Eohaid Forgaill (530-598) was a Latin scholar and “King of the Poets.” He was said to have spent so much time studying that he went blind, and was give the name Dallán, “Little Blind One.” He wrote the poem, “Rop tú mo Baile” (Be Thou my Vision) asking God to be his vision. But “vision” here means more than physical sight. The original Irish word “baile” mean “vision” or “rapture,” in the sense used by the Old Testament prophets. The language of this hymn is drawn from traditional Irish culture: it uses heroic imagery to describe God. This was characteristic of medieval Irish poetry, which cast God as the ‘chieftain’ or ‘High King’ (Ard Ri) who provided protection to his people or clan.

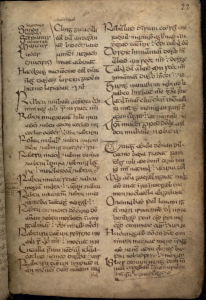

14th C. Manuscript MG 3, National Library of Ireland

14th C. Manuscript MG 3, National Library of Ireland

containing “Rob tu mo bhoile”

The Irish monk Eohaid Forgaill (530-598) was a Latin scholar and “King of the Poets.” He was said to have spent so much time studying that he went blind, and was give the name Dallán, “Little Blind One.” He wrote the poem, “Rop tú mo Baile” (“Be Thou my Vision”) asking God to be his vision But “vision” here means more than physical sight. The original Irish word “baile” mean “vision” or “rapture,” in the sense used by the Old Testament prophets.

This was translated into literal prose by Irish scholar Mary Byrne (1880-1931), a Dublin native, and then published in Eriú, the journal of the School of Irish Learning, in 1905. Eleanor Hull (1860-1935b), born in Manchester, was the founder of the Irish Text Society and president of the Irish Literary Society of London. Hull versified the text and it was published in her Poem Book of the Gael (1912).

Irish liturgy and ritual scholar Helen Phelan, a lecturer at the University of Limerick, points out how the language of this hymn is drawn from traditional Irish culture: “One of the essential characteristics of the text is the use of ‘heroic’ imagery to describe God. This was very typical of medieval Irish poetry, which cast God as the ‘chieftain’ or ‘High King’ (Ard Ri) who provided protection to his people or clan. The lorica (Latin: breastplate) is one of the most popular forms of this kind of protection prayer and is very prevalent in texts of this period.” St. Patrick’s Breastplate (1940 The Hymnal, #268) is in this genre.

Hull’s verse version was paired with the Irish tune SLANE in The Irish Church Hymnal in 1919. The folk melody was taken from a non-liturgical source, Patrick Weston Joyce’s Old Irish Folk Music and Songs: A Collection of 842 Airs and Songs hitherto unpublished (1909).

“Most ‘traditional’ Irish religious songs are non-liturgical,” says Dr. Phelan. “There is a longstanding practice of ‘editorial weddings’ in Irish liturgical music, where traditional tunes were wedded to more liturgically appropriate texts. This is a very good example of this practice.”

Back in 433 AD, on the eve of Bealtine, a Druidic Holiday that lines up directly with Easter as well as the spring equinox, it was declared by the King, Leoghaire (Leary) Mac Neill, that no fires were to be lit until the fire atop of Tara Hill was lit. Going against the kings wishes, St. Patrick went out to Slane Hill and lit a candle to celebrate the resurrection of Christ. The king was so impressed by the courage that St. Patrick had shown, Leoghaire let him continue his missionary work throughout Ireland. The tune was given the name SLANE to commemorate this event.

English translation by Mary Byrne, 1905:

Be thou my vision O Lord of my heart

None other is aught but the King of the seven heavens.Be thou my meditation by day and night.

May it be thou that I behold even in my sleep.Be thou my speech, be thou my understanding.

Be thou with me, be I with theeBe thou my father, be I thy son.

Mayst thou be mine, may I be thine.Be thou my battle-shield, be thou my sword.

Be thou my dignity, be thou my delight.Be thou my shelter, be thou my stronghold.

Mayst thou raise me up to the company of the angels.Be thou every good to my body and soul.

Be thou my kingdom in heaven and on earth.Be thou solely chief love of my heart.

Let there be none other, O high King of Heaven.Till I am able to pass into thy hands,

My treasure, my beloved through the greatness of thy loveBe thou alone my noble and wondrous estate.

I seek not men nor lifeless wealth.Be thou the constant guardian of every possession and every life.

For our corrupt desires are dead at the mere sight of thee.Thy love in my soul and in my heart —

Grant this to me, O King of the seven heavens.O King of the seven heavens grant me this —

Thy love to be in my heart and in my soul.With the King of all, with him after victory won by piety,

May I be in the kingdom of heaven O brightness of the son.Beloved Father, hear, hear my lamentations.

Timely is the cry of woe of this miserable wretch.O heart of my heart, whatever befall me,

O ruler of all, be thou my vision.

Here is the hymnal version. Verse three is usually omitted.

Be Thou my Vision, O Lord of my heart;

Naught be all else to me, save that Thou art;

Thou my best Thought, by day or by night,

Waking or sleeping, Thy presence my light.Be Thou my Wisdom, and Thou my true Word;

I ever with Thee and Thou with me, Lord;

Thou my great Father, I Thy true son;

Thou in me dwelling, and I with Thee one.Be Thou my battle Shield, Sword for the fight;

Be Thou my Dignity, Thou my Delight;

Thou my soul’s Shelter, Thou my high Tow’r:

Raise Thou me heav’nward, O Pow’r of my pow’r.Riches I heed not, nor man’s empty praise,

Thou mine Inheritance, now and always:

Thou and Thou only, first in my heart,

High King of Heaven, my Treasure Thou art.High King of Heaven, my victory won,

May I reach Heaven’s joys, O bright Heav’n’s Sun!

Heart of my own heart, whate’er befall,

Still be my Vision, O Ruler of all.

Although there are hundreds of versions of Be Thou my vision on the Internet, all the vocals ones are not very satisfactory.

Here is the Mormon Tabernacle Choir. Here is King’s College, Cambridge.Here it is arranged as an art song. Here sung in Modern Irish.

Here is a charming version for violin and harp. A good arrangement for cello and piano. Of course for Celtic instruments. For string quartet. For brass quintet! For marching band!!

_____________________________

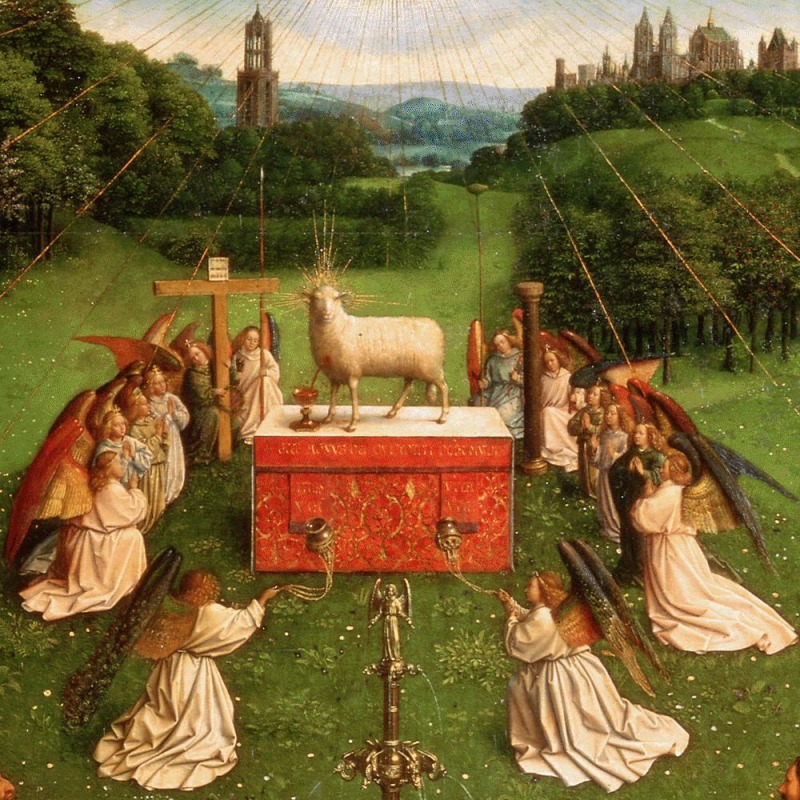

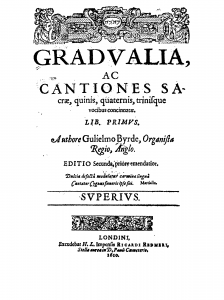

Immortal, Invisible, God only wise, by William Chalmers Smith (1824—1908), is a proclamation of the transcendence of God: “To the King of ages, immortal, invisible, the only God, be honor and glory for ever and ever” (1 Tim 17). No man has ever seen God, who dwells in inaccessible light that is darkness to mortal eyes. God lacks nothing (“nor wanting”) and never changes (“nor wasting”), and is undying, unlike mortals, who in a striking image “blossom and flourish like leaves on the tree, then wither and perish.” The original ending of the hymn completes the thought: “And so let Thy glory, almighty, impart, / Through Christ in His story, Thy Christ to the heart.” “No one has ever seen God; the only Son, who is in the bosom of the Father, He has made Him known” (John 1:18). Only in Jesus through the proclamation of the Gospel can we know the Father.

Immortal, invisible, God only wise,

in light inaccessible hid from our eyes,

most blessed, most glorious, the Ancient of Days,

almighty, victorious, thy great name we praise.Unresting, unhasting, and silent as light,

nor wanting, nor wasting, thou rulest in might:

thy justice, like mountains high soaring above,

thy clouds which are fountains of goodness and love.To all, life thou givest, to both great and small;

in all life thou livest, the true life of all;

we blossom and flourish like leaves on the tree,

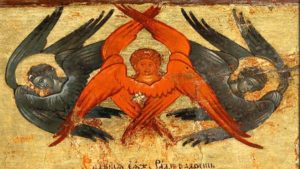

then wither and perish, but naught changeth thee.Thou reignest in glory, thou dwellest in light,

thine angels adore thee, all veiling their sight;

all praise we would render; O help us to see

’tis only the splendor of light hideth thee!

The final stanzas have been somewhat altered from the original:

Great Father of glory, pure Father of light,

Thine angels adore Thee, all veiling their sight;

Of all Thy rich graces this grace, Lord, impart

Take the veil from our faces, the vile from our heart.All laud we would render; O help us to see

’Tis only the splendor of light hideth Thee,

And so let Thy glory, almighty, impart,

Through Christ in His story, Thy Christ to the heart.

Here is Christ Church Cathedral in Indianapolis.

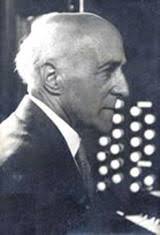

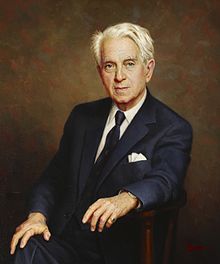

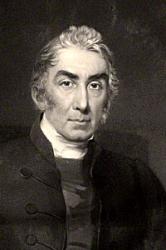

Walter Chalmers Smith

Walter Chalmers Smith D. D. (1824-1908) was educated at the Grammar School and University of that City. He pursued his Theological studies at Edinburgh, and was ordained Pastor of the Scottish Church in Chadwell Street, Islington, London, in 1850. After holding several pastorates he became, in 1876, Minister of the Free High Church, Edinburgh. The Free Church of Scotland elected him its moderator during its Jubilee year in 1893.

“From 1860 to 1893 Dr. Smith published the following volumes of verse: “The Bishop’s Walk” (1860); “Hymns of Christ and the Christian Life” (1867); “Olrig Grange” (1872); “Borland Hall” (1874); “Hilda; among the Broken Gods” (1878); “Raban; or, Life Splinters” (1880); “North Country Folk” (1883); “Kildrostan” (1884); “Thoughts and Fancies for Sunday Evenings” (1887); “A Heretic and other Poems” (1891); “Selections from the Poems of Walter C. Smith” (1893).

Although Dr. Smith’s work has a claim to a place among that of the general poets, there is a certain fitness in his being placed among the sacred poets, since the strongest force in his poetry is the religious one, so that, even in what may be called his secular poetry, the most vital parts grow out of his theologic thought or religious feeling. In this respect he is like the other poet of Aberdeenshire, George MacDonald, who says himself, that he would not care either to write poetry or tell stories if he could not preach in them—but then there is preaching and preaching; and if all preaching were of the living sort we get from these two Aberdonians, the name would carry a higher meaning than it usually does.” (William Horder)

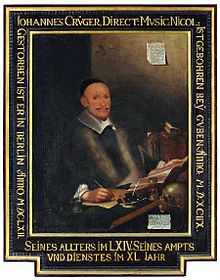

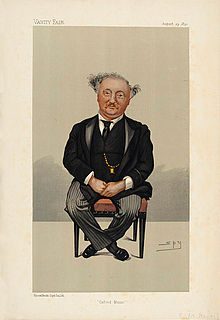

John Roberts

John Roberts, in Welsh Ieuan Gwyllt (1822-1877), composed the tune ST. DENIO (also known as JOANNA, or PALESTINA). It is derived from a Welsh folk song Can Mlynned i ‘nawr’ (“A Hundred Years from Now”). This version appeared in his Canaidau y Cyssegr (Songs of Worship) of 1839. The melody was first harmonized to, adapted for, and used with Smith’s words in The English Hymnal of 1905-1906, edited by Gustav Theodore Holst (1874-1934). Roberts was a leader in the revival of Welsh choral song.

This hymn was sung in Westminster Abbey, London, England, at the 2002 funeral of Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother. It is Prince Charles’s favorite hymn and was sung at his wedding to Camilla. Here it is sung at a memorial service for the victims of the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center in New York City and on the Pentagon in Washington from St Paul’s Cathedral, 14th September 2001.

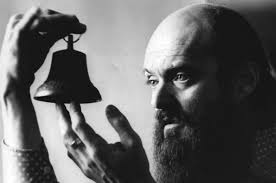

As Librarian of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, Christopher de Hamel has charge of The Gospels of St. Augustine, the very manuscript that Pope Gregory the Great (540—604) gave to St. Augustine of Canterbury (543—604) to take to England. De Hamel carried it in the procession of the enthronement of Rowan Williams as Archbishop of Canterbury in 2003.

Rowan Williams venerating the Gospel Book of St. Augustine

In his book, Meetings with Remarkable Manuscripts, de Hamel recounts:

“I had to enter the cathedral that day through the west door, joining the procession just as they began singing the first hymn, ‘immortal, invisible, God only wise,’ a Welsh tune in homage to the nationality of the new primate. I was holding the Gospels of St. Augustine open of a cushion. It was secured by two ribbons of transparent conservation tape. Upwards of 2,500 people singing a familiar hymn very loudly in an enclosed stone building makes the air vibrate. This is the nature of sound waves. The parchment leaves of the manuscript, as we saw earlier, are extremely fine and of tissue thinness, and they picked up the vibrations and they hummed and fluttered in time to the music. At that moment it was as if the sixth-century manuscript on its cushion had come to life and was taking part in the service.”