Mount Calvary Church

Eutaw Street and Madison Avenue

Baltimore, Maryland

A Roman Catholic Parish of

The Personal Ordinariate of the Chair of St. Peter

Anglican Use

Rev. Albert Scharbach, Pastor

Easter VI

May 6, 2018

8:00 AM Said Mass

10:00 AM Sung Mass

________________________

Prelude

Christ lag in Todesbanden, Pachelbel

Hymns

Christ Jesus lay in death’s strong bands (CHRIST LAG IN TODESBANDEN)

Come down, o Love divine (DOWN AMPNEY)

Alleluia! sing to Jesus (HYFRYDOL)

Anthems

A new commandment, Thomas Tallis

Regina coeli, laetare, Charpentier

Common

Missa S. Maria Magdelena, Healey Willan

Postlude

Fantasy on Hyfrydol, Henry Coleman

_________________

Prelude

Christ lag in Todesbanden, Pachelbel

Here is the prelude.

________________________

Hymns

Christ Jesus lay in death’s strong bands (CHRIST LAG IN TODESBANDEN)

Martin Luther wrote this adaptation of the Easter sequence, Victimae paschali laudes. The hymn captures the essence of the classic struggle between life and death. The resurrection represents the apex of this battle. With Christ’s rising from the grave, the “strong bands” of death were broken. Stanza two talks about a “strange and dreadful strife” between the powers of life and death. But the victory went to life when death was “stripped of power.” The sting of death (I Corinthians 15:56) “is lost forever.” The third stanza is one of rejoicing because “Christ is himself the joy of all.” “The Sun” both warms and lights us. “The night of sin is ended.” The final stanza would have been seen in light of the Eucharist with a reference that contrasts the “true bread of heaven” with the “old and wicked leaven” (Mt 16:6) . The reference to the Eucharist is even stronger as the hymn closes:

Christ alone our souls will feed;

he is our meat and drink indeed;

faith lives upon no other! Alleluia!

1 Christ Jesus lay in death’s strong bands,

for our offenses given;

but now at God’s right hand He stands

and brings us light from heaven.

Therefore let us joyful be

and sing to God right thankfully

loud songs of hallelujah.

Alleuia!2 It was a strange and dreadful strife

when life and death contended;

the victory remained with life,

the reign of death was ended.

Holy Scripture plainly saith

that death is swallowed up by death;

his sting is lost forever.

Alleluia!3 Here the true Paschal Lamb we see,

whom God so freely gave us;

He died on the accursed tree –

so strong His love to save us.

See, His blood doth mark our door;

faith points to it, death passes o’er,

and Satan cannot harm us.

Hallelujah!4 Then let us feast this Easter Day

On Christ, the bread of heaven;

The Word of grace has purged away

The old and evil leaven.

Christ alone our souls will feed;

He is our meat and drink indeed;

Faith lives upon no other!

Alleluia!

Here is a festival version with organ and orchestra. Here is a dramatized version with Luther at the organ and Katherine von Bora singing.

Here are the seven original stanzas:

Christ lag in Todesbanden

Für unsre Sünd gegeben,,

Er ist wieder erstanden

Und hat uns bracht das Leben;

Des wir sollen fröhlich sein,,

Gott loben und ihm dankbar sein

Und singen halleluja,,

Halleluja!Christ lay in death’s bonds

handed over for our sins,

he is risen again

and has brought us life

For this we should be joyful,

praise God and be thankful to him

and sing allelluia,

Alleluia2

Den Tod niemand zwingen kunnt

Bei allen Menschenkindern,.

Das macht’ alles unsre Sünd,

Kein Unschuld war zu finden..

Davon kam der Tod so bald

Und nahm über uns Gewalt,

Hielt uns in seinem Reich gefangen..

Halleluja!Nobody could overcome death

among all the children of mankind.

Our sin was the cause of all this,

no innocence was to be found.

Therefore death came so quickly

and seized power over us,.

held us captive in his kingdom.

Alleluia !3

Jesus Christus, Gottes Sohn,,

An unser Statt ist kommen

Und hat die Sünde weggetan,

Damit dem Tod genommen

All sein Recht und sein Gewalt,

Da bleibet nichts denn Tods Gestalt,

Den Stach’l hat er verloren.

Halleluja!Jesus Christ, God’s son,

has come to our place

and has put aside our sins,

and in this way from death has taken

all his rights and his power,

here remains nothing but death’s outward form,

it has lost its sting.

Alleluia!4

Es war ein wunderlicher Krieg,

Da Tod und Leben rungen,

Das Leben behielt den Sieg,,

Es hat den Tod verschlungen.

Die Schrift hat verkündigt das,

Wie ein Tod den andern fraß,

Ein Spott aus dem Tod ist worden.

Halleluja!It was a strange battle

where death and life struggled.

Life won the victory,

it has swallowed up death

Scripture has proclaimed

how one death ate the other,

death has become a mockery.

Alleluia5

Hier ist das rechte Osterlamm,

Davon Gott hat geboten,

Das ist hoch an des Kreuzes Stamm

In heißer Lieb gebraten,

Das Blut zeichnet unsre Tür,

Das hält der Glaub dem Tode für,

Der Würger kann uns nicht mehr schaden.

Halleluja!Here is the true Easter lamb

that God has offered

which high on the trunk of the cross

is roasted in burning love,

whose blood marks our doors,

which faith holds in front of death,

the strangler can harm us no more

Alleluia6

So feiern wir das hohe Fest

Mit Herzensfreud und Wonne,

Das uns der Herre scheinen läßt,

Er ist selber die Sonne,

Der durch seiner Gnade Glanz

Erleuchtet unsre Herzen ganz,

Der Sünden Nacht ist verschwunden..

Halleluja!Thus we celebrate the high feast

with joy in our hearts and delight

that the Lord lets shine for us,

He is himself the sun

who through the brilliance of his grace

enlightens our hearts completely,

the night of sin has disappeared.

Alleluia !7

Wir essen und leben wohl

In rechten Osterfladen,

Der alte Sauerteig nicht soll

Sein bei dem Wort Gnaden,

Christus will die Koste sein

Und speisen die Seel allein,,

Der Glaub will keins andern leben..

Halleluja!We eat and live well

on the right Easter cakes,

the old sour-dough should not

be with the word grace,

Christ will be our food

and alone feed the soul,

faith will live in no other way.

Alleluiia!

The original version had seven stanzas and appeared first in Enchiridion (1524). Richard Massie (1800-1887) provided an English translation of all seven German stanzas in Martin Luther’s Spiritual Songs(1854). Massie, an Englishman and rector of St. Bride’s Church in Chester, was self-taught in German, but became one of the leading translators of hymns from the German of his day. The shortening of the hymn to four stanzas in English took place later in the 19th century in the Church of England Hymn Book

CHRIST LAG IN TODESBANDEN is an adaptation of a medieval chant used for “Victimae Paschali laudes”. The tune’s arrangement is credited to Johann Walther (b. Kahla, Thuringia, Germany, 1496: d. Torgau, Germany, 1570), in whose 1524 Geystliche Gesangk Buchleyn it was first published. But it is possible that Luther also had a hand in its arrangement. Walther was one of the great early influences in Lutheran church music. At first he seemed destined to be primarily a court musician. A singer in the choir of the Elector of Saxony in the Torgau court in 1521, he became the court’s music director in 1525. After the court orchestra was disbanded in 1530 and reconstituted by the town, Walther became cantor at the local school in 1534 and directed the music in several churches. He served the Elector of Saxony at the Dresden court from 1548 to 1554 and then retired in Torgau. Walther met Martin Luther in 1525 and lived with him for three weeks to help in the preparation of Luther’s German Mass. In 1524 Walther published the first edition of a collection of German hymns, Geystliche gesangk Buchleyn. This collection and several later hymnals compiled by Walther went through many later editions and made a permanent impact on Lutheran hymnody. One of the earliest and best-known Lutheran chorales, CHRIST LAG IN TODESBANDEN is a magnificent tune in rounded bar form (AABA).

_______________________

Come down, o Love divine (DOWN AMPNEY)

Bianco of Siena (c. 1345-c. 1412) was born in Anciolina, a small hamlet in Tuscany, Italy, but moved at a young age to Siena where he labored as a wood carver. We have little information about the life of this mystic; what we do know is due to the efforts of Feo Belcari (1410-1484), a poet and playwright from Florence, who reconstructed Bianco’s biography from his poetry.

According to Medieval Italy: An Encyclopedia, edited by Christopher Kleinhenz, “Bianco joined the Gesuati, a lay order founded by Giovanni Colombini, and lived for a number of years in a monastery of the order in Cittè di Castello. He spent the last years of his life in Venice.”

Bianco composed in the laude form, a vernacular sacred song used outside of the medieval Catholic liturgy. Lauda spirituale were popular well into the 19th century. Most laude were composed in a melody-only form—though polyphonic, or multi-part, laude developed in Italy in the early 15th century.

Bianco’s more than 100 laude may be divided into two groups—doctrinal and mystical. In Dr. Kleinhenz’s volume, we gain insight into Bianco’s poetry: “Inspired by intense religious zeal, his poetry has its mystical roots in that of Jacopone da Todi, particularly in regard to the theme of divine madness. The immediacy of Bianco’s language and the unadorned simplicity of his statements enhanced the popular appeal of his poetry.”

“Come Down, O Love Divine” (“Discendi, amor santo”) is a translation of four of the original eight stanzas from Laudi Spirituali del Bianco de Siena, Lucca, 1851.

Richard Littledale (1833-1890), an Irish scholar and minister, translated four of the stanzas that appeared in the People’s Hymnal (1867). The hymn’s popularity increased significantly after it appeared in the English Hymnal (1906), one of the most influential hymnals of the early 20th century, with a musical setting by the eminent English composer Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958).

Stanza three of the four English-language stanzas is omitted from most hymnals:

Let holy charity

Mine outward vesture be,

And lowliness become mine inner clothing;

True lowliness of heart,

Which takes the humbler part,

And o’er its own shortcomings weeps with loathing.

While the stanza starts out strongly, the translation seems strained and lacks the directness and beauty of the remaining three stanzas. Lutheran hymn writer Gracia Grindal notes that “the entire hymn is an invocation to the Holy Spirit [to] ‘kindle’ the heart so that it burns with the ardor of the Spirit.”

The text is intense—intensely personal and intensely passionate. The incipit (first line) invokes the Holy Spirit to “seek thou this soul of mine and visit it with thine own ardor glowing.” Classic images of Pentecost appear throughout the hymn, especially those that relate to fire. Stanza one mentions “ardor glowing” and “kindle . . . thy holy flame.” Stanza two continues the flame images with “freely burn,” “dust and ashes in its heat consuming.”

The final stanza is a powerful statement of total commitment to love, to “create a place/wherein the Holy Spirit makes a dwelling.”

1 Come down, O Love divine,

seek thou this soul of mine,

and visit it with thine own ardor glowing;

O Comforter, draw near,

within my heart appear,

and kindle it, thy holy flame bestowing.2 O let it freely burn,

till earthly passions turn

to dust and ashes in its heat consuming;

and let thy glorious light

shine ever on my sight,

and clothe me round, the while my path illuming.3 And so the yearning strong,

with which the soul will long,

shall far outpass the power of human telling;

for none can guess its grace,

till he become the place

wherein the Holy Spirit makes His dwelling.

Here is the choir of King’s College, Cambridge.

The Old Vicarage in Down Ampney was the birthplace of Ralph Vaughan Williams in 1872. A tune he composed, used for the hymn “Come Down, O Love Divine”, is titled “Down Ampney” in its honour.

______________________________

Alleluia! sing to Jesus (HYFRYDOL)

Alleluia! sing to Jesus was written by William Chatterton Dix (1837—1898). Revelation 5:9 describes this eschatological scene of joy and glory: “And they sang a new song, saying: ‘You are worthy to take the scroll and to open its seals, because You were slain, and with Your blood You purchased for God members of every tribe and language and nation.’” Dix invites us to sing that new song of praise to our ascended Savior. This hymn is a declaration of Jesus’ victory over death and His continued presence among His people. By complex and interlocking allusions to Scripture, it presents a very high view of the Eucharist presence: Jesus is both “Priest and Victim” in this feast. Jesus, having triumphed over sin and death, “robed in flesh” has ascended above all the heavens, entering “within the veil” to the very throne of God. Dix sees in the Eucharist the fulfillment of Jesus’ promise to be with us evermore.

We sometimes forget that Jesus ever intercedes for us. The Mount Calvary Magazine in 1910 reminded us:

“The Incarnation is a permanent thing, it still exists. Our Lord still has His work to do in His glorified humanity; and that work is the perpetual intercession which He ever liveth to make for us. In order that he might carry on that work, it was necessary that His humanity should ascend into Heaven; and the way in which he now carries it on, is the unceasing presentation of His living and glorified humanity to the Father.” He is thereby fulfilling His promise that is in the verse painted on the sanctuary arch.

1 Alleluia! sing to Jesus!

His the sceptre, His the throne;

Alleluia! His the triumph,

His the victory alone:

Hark! the songs of peaceful Sion

Thunder like a mighty flood;

Jesus, out of every nation

Hath redeemed us by His blood.2 Alleluia! not as orphans

Are we left in sorrow now;

Alleluia! He is near us,

Faith believes, nor questions how:

Though the cloud from sight received Him,

When the forty days were o’er:

Shall our hearts forget His promise,

“I am with you evermore”?3 Alleluia! Bread of Heaven,

Thou on earth our Food, our Stay!

Alleluia! here the sinful

Flee to thee from day to day:

Intercessor, Friend of sinners,

Earth’s Redeemer, plead for me,

Where the songs of all the sinless

Sweep across the crystal sea.4 Alleluia! King eternal,

Thee the Lord of lords we own;

Alleluia! born or Mary,

Earth Thy footstool, heaven Thy throne:

Thou within the veil hast entered,

Robed in flesh, our great High-Priest;

Thou on earth both Priest and Victim

In the Eucharistic feast.5 Alleluia! sing to Jesus!

His the sceptre, His the throne;

Alleluia! His the triumph,

His the victory alone;

Hark! the songs of holy Sion

Thunder like a mighty flood;

Jesus, out of every nation

Hath redeemed us by His blood.

Here is the hymn at St. Bartholomew’s.

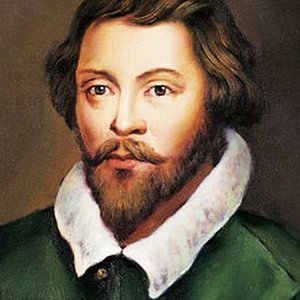

William Chatterton Dix

William Chatterton Dix (1837 – 1898) was an English writer of hymns and carols. He was born in Bristol, the son of John Dix, a local surgeon. His father gave him his middle name in honour of Thomas Chatterton, a poet about whom he had written a biography. He was educated at the Grammar School, Bristol, for a mercantile career, and became manager of a maritime insurance company in Glasgow where he spent most of his life.

At the age of 29 he was struck with a near fatal illness and consequently suffered months confined to his bed. During this time he became severely depressed. Yet it is from this period that many of his hymns date. He died at Cheddar, Somerset, England.

___________________________________

Anthems

A new commandment, Thomas Tallis

A new commandment give I unto you, saith the Lord, that ye love together, as I have loved you, that even so ye love one another. By this shall every man know that ye are my disciples, if ye have love one to another.

Here are three voices.

Little is known about Thomas Tallis’s early life, but there seems to be agreement that he was born in the early 16th century, toward the close of the reign of Henry VII. Little is also known about Tallis’s childhood and his significance with music at that age. However, there are suggestions that he was a Child (boy chorister) of the Chapel Royal, St. James’ Palace, the same singing establishment which he later joined as a Gentleman. His first known musical appointment was in 1532, as organist of Dover Priory (now Dover College), a Benedictine priory in Kent. His career took him to London, then (probably in the autumn of 1538) to Waltham Abbey, a large Augustinian monastery in Essex which was dissolved in 1540. Tallis was paid off and also acquired a volume and preserved it; one of the treatises in it, by Leonel Power, prohibits consecutive unisons, fifths, and octaves.

Tallis’s next post was at Canterbury Cathedral. He was next sent to Court as Gentleman of the Chapel Royal in 1543 (which later became a Protestant establishment), where he composed and performed for Henry VIII,[9] Edward VI (1547–1553), Queen Mary (1553–1558), and Queen Elizabeth I (1558 until Tallis died in 1585). Throughout his service to successive monarchs as organist and composer, Tallis avoided the religious controversies that raged around him, though, like William Byrd, he stayed an “unreformed Roman Catholic.” Tallis was capable of switching the style of his compositions to suit the different monarchs’ vastly different demands. Among other important composers of the time, including Christopher Tye and Robert White, Tallis stood out. Walker observes, “He had more versatility of style than either, and his general handling of his material was more consistently easy and certain.” Tallis was also a teacher, not only of William Byrd, but also of Elway Bevin, an organist of Bristol Cathedral, and Gentleman of the Chapel Royal.

Tallis married around 1552; his wife, Joan, outlived him by four years. They apparently had no children. Late in his life he lived in Greenwich, possibly close to the royal palace: a local tradition holds that he lived on Stockwell Street.

Queen Mary granted Tallis a lease on a manor in Kent that provided a comfortable annual income. In 1575, Queen Elizabeth granted to him and William Byrd a 21-year monopoly for polyphonic music and a patent to print and publish music, which was one of the first arrangements of that type in the country. Tallis’s monopoly covered ‘set songe or songes in parts’, and he composed in English, Latin, French, Italian, or other tongues as long as they served for music in the Church or chamber. Tallis had exclusive rights to print any music, in any language. He and William Byrd were the only ones allowed to use the paper that was used in printing music. Tallis and Byrd used their monopoly to produce Cantiones quae ab argumento sacrae vocantur in 1575, but the collection did not sell well and they appealed to Queen Elizabeth for her support. People were naturally wary of their new publications, and it certainly did not help their case that they were both avowed Roman Catholics. Not only that, they were strictly forbidden to sell any imported music. “We straightly by the same forbid…to be brought out of any forren Realmes…any songe or songes made and printed in any foreen countrie.” Also, Byrd and Tallis were not given “the rights to music type fonts, printing patents were not under their command, and they didn’t actually own a printing press.”

Tallis retained respect during a succession of opposing religious movements and deflected the violence that claimed Catholics and Protestants alike. He died peacefully in his house in Greenwich in November 1585.

Regina coeli, laetare, Charpentier

Here is the motet.

_____________________________________________________________

Common

Missa S. Maria Magdelena, Healey Willan

_________________________________________

Postlude

Fantasy on Hyfrydol, Henry Coleman

Richard Henry Pinwill Coleman was born on 3 April 1888 in Dartmouth. He was a chorister in St George’s Church, Ramsgate before going to Denstone College.

He studied organ under Sydney Nicholson at Carlisle Cathedral and Manchester Cathedral.