Mount Calvary Church

Baltimore

Personal Ordinariate of the Chair of St. Peter

Lazarus Sunday

April 2, 2017

Hymns

I heard the voice of Jesus say

What wondrous love

Thou art the Way

Anthems

When Jesus wept, the falling tear, William Billings

I am the Resurrection, Thomas Morley

Common

Kyrie, Sanctus, Agnus Dei, Merbecke

_______________________________

I heard the voice of Jesus say was written by the Scots clergyman Horatius Bonar (1808–1889). The Lord’s invitations to us, and the promises attached to them, are conditioned only upon are coming to Him. They require no special preparations or qualifications, nor do they depend on our own “righteousness.” The only sacrifice He requires is “a broken and a contrite heart.” (Psalm 51:17) We need but “come” and “drink,” and Christ’s infinite blessings are poured out upon us. We are made clean and a new creation not by ourselves, but through His atoning sacrifice on the Cross. May every one that is weary and thirsting for a better, eternal life hear and accept the Lord’s gracious invitations to come, rest, drink, and live through and in Him.

Here are Tim Callies comments:

Horatius Bonar

“Horatius Bonar was born in 1808 in Edinburgh, Scotland, the son of a ruling elder in the Church of Scotland. After a relatively uneventful upbringing, Bonar entered into the ministry himself, becoming pastor of the North Parish in the rural town of Kelso.

Not long after he entered the ministry there was a disruption in the Church of Scotland that resulted in the withdrawal of 451 ministers from the Established church, among whom were Bonar and a number of his friends. Together they formed The Free Church of Scotland.

Bonar spent the next 20 years pastoring the congregation in Kelso, writing, and engaging in evangelism. Throughout his life he had been strongly influenced by Thomas Chalmers, and in 1866 he planted a new church in his home city of Edinburgh: the Chalmers Memorial Chapel. He was to serve that church until the year before his death in 1889.

In Bonar’s day the Scottish church had no substantial library of hymns since they sang metrical Psalms almost exclusively. Bonar had begun to write hymns before his ordination when he was serving as superintendent of a Sunday school. He found that the youth had little love for either the words or the tunes they were singing, so he set out to write a few hymns with simpler lyrics and already familiar tunes. These hymns were received wonderfully.

It wasn’t long after this that Bonar, apparently having a gift and an interest in writing verse, took to writing adult hymns. This continued as a habit while he served as pastor, and in the course of his ministry he published a number of hymn compilations.

“I Heard the Voice of Jesus Say” was one of the hymns he wrote during his tenure at Kelso. This is perhaps his most famous song, having found good reception not only in Scotland but also in the wider English-speaking world.

What makes the hymn so widely appealing may well be its focus on the gospel call of Christ to come to him, look to him, drink, and rest, and the simple call to obey and to find in him all that he has promised. It is simple, sweet and encouraging.

Down through the centuries many have observed how people of true faith tend to exhibit an uncommon degree of confidence, courage, resilience, and inner peace. It’s not that they don’t occasionally suffer doubt, fear, sorrow, or discouragement, but they’re able to fight through these challenges and emerge in a better place. Why? Perhaps it’s faith that we have a Savior who traded his Heavenly glory and His mortal life to save us from our own sin, who provides us a sure refuge and guidance in times of trial, and who has kept for us an eternal and blissfully happy home with Him. Believers know these things because He promised them Himself, in the Gospel!”

I heard the voice of Jesus say,

‘Come unto me and rest;

lay down, thou weary one, lay down

thy head upon my breast’:

I came to Jesus as I was,

weary and worn and sad;

I found in him a resting-place,

and he has made me glad.

I heard the voice of Jesus say,

‘Behold, I freely give

the living water, thirsty one;

stoop down and drink and live’:

I came to Jesus, and I drank

of that life-giving stream;

my thirst was quenched, my soul revived,

and now I live in him.I heard the voice of Jesus say,

‘I am this dark world’s light;

look unto me, thy morn shall rise,

and all thy day be bright’:

I looked to Jesus, and I found

in him my star, my sun;

and in that light of life I’ll walk

till travelling days are done.

It has been rendered into Latin by Dr. Macgill in his Songs of the Christian Creed and Life, 1876.

Loquentem exaudivi

Jesum : “Veni, quiesce,

Sino meo defrssus

Caput tu requiesce.”

Lassus fui et veni,

Tristis, gravis labore,

Et in Eo quievi,

Deposito delore.Loqentem et audivi:

“Tibi do Ego sponte,

Sititor, aquam vivam;

Vivas bibens de Fonte.”

Simulque veni,bibi

Et in anima renata

Vivico de rivo,

Vivo, siti sedata.Loqentem et audivi:

“Lux sum, tibi videnti

Me, lumen afflugebit

Tota die nitenti.”

Vidi, refulsit Ille,

Nocturnus, matutinus,

Eiusque luce domum

Incedo peregrinus.

The tune KINGSFOLD is an old English folk song. The tune is written in e minor, but also can be considered a modal tune. The tune was published in English Country Songs (1893), an anthology compiled by Lucy E. Broadwood and J. A. Fuller Maitland. It wasn’t until Ralph Vaughn Williams (1872-1958) heard this folk song in Kingsfold, Sussex, England, that the tune was actually named. After Vaughn Williams had heard the tune, he decided to arrange the tune for the text of “I Heard the Voice of Jesus Say” for the English Hymnal (1906).

Here is the choir of Manchester Cathedral. Here is a fantasy on Kingsfold for handbells. Here a fantasy meditation for organ.

“I Heard the Voice of Jesus Say” is one of the commonly lined-out hymns,

In “lining out,” the leader tells the coming verse or line to be repeated by the congregation (as opposed to call and response, where the leader sings a line and the congregation responds with a standard line that remains constant throughout the song). Lined out hymns usually have a steady slow beat and are sung early in the service (as opposed to “shouts” which typically are fast and, if anything, gain speed, and are sung late in the service.

Here it is sung as a lined-out hymn with choir and without choir.

_____________________

What wondrous love is an American folk hymn, as its repetitions evidence, from the Second Great Awakening. This hymn articulates the question that Christians ask every day: what did I do to deserve such a wonderful love from God and from Christ? The hymn is an offering of thanks to the Son for laying aside his crown as King and humbling himself even unto death. Jesus took on the sin and shame of man and thereby became the Lamb who was slain to save our sins. Jesus is not only the Lamb, but he is I AM, Lord and God. Our response is endless praise forever and ever, and forever we shall marvel and ask, “What wondrous Love?”

What wondrous love is this, O my soul, O my soul!

What wondrous love is this, O my soul!

What wondrous love is this that caused the Lord of bliss

to bear the dreadful curse for my soul, for my soul,

to bear the dreadful curse for my soul?When I was sinking down, sinking down, sinking down,

when I was sinking down, sinking down;

when I was sinking down beneath God’s righteous frown,

Christ laid aside his crown for my soul, for my soul,

Christ laid aside his crown for my soul.To God and to the Lamb, I will sing, I will sing,

to God and to the Lamb, I will sing;

to God and to the Lamb who is the great I AM –

while millions join the theme, I will sing, I will sing;

while millions join the theme, I will sing.And when from death I’m free, I’ll sing on, I’ll sing on,

and when from death I’m free, I’ll sing on;

and when from death I’m free, I’ll sing and joyful be,

and through eternity, I’ll sing on, I’ll sing on,

and through eternity I’ll sing on.

As a folk hymn the exact history of What wondrous love is not entirely clear. It is sometimes described as a “white spiritual”, from the American South.

The hymn’s lyrics were first published in Lynchburg, Virginia in the c. 1811 camp meeting songbook A General Selection of the Newest and Most Admired Hymns and Spiritual Songs Now in Use. The lyrics may also have been printed, in a slightly different form, in the 1811 book Hymns and Spiritual Songs, Original and Selected, published in Lexington, Kentucky. (It was included in the third edition of this text published in 1818, but all copies of the first edition have been lost.) In most early printings, the hymn’s text was attributed to an anonymous author, though the 1848 hymnal The Hesperian Harp attributes the text to a Methodist pastor from Oxford, Georgia, named Alexander Means.

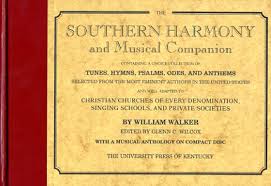

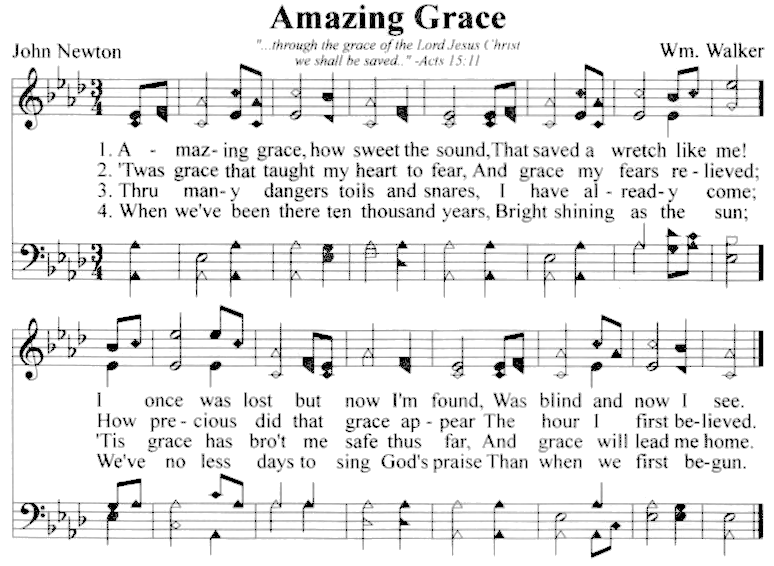

The tune was discovered by composer William Walker on his journey through the Appalachian region of America. Though the tune had been around for many years, it was passed on by rote, and not written down. Walker decided in 1835 that he would change that, and added the hymn to his collection Southern Harmony. The Appalachian region is well known for having many Irish and Scottish immigrants, which is shown in the hymns haunting text and minor tune. The hymn is written in a way that made it easy to pass on from generation to generation, repetition of lyrics. The hymn was written in the early 1800’s, a time when hymnals were scarce and music was rarely written down. To make it easier for people to learn hymns (Especially in the time of the Second Great Awakening), the author would often times write the same lyrics over and over again to drive home the point, while still keeping the text simple and easy to learn.

The hymn is sung in Dorian mode, giving it a haunting quality. Though The Southern Harmony and many later hymnals incorrectly notated the song in Aeolian mode (natural minor), even congregations singing from these hymnals generally sang in Dorian mode by spontaneously raising the sixth note a half step wherever it appeared. Twentieth-century hymnals generally present the hymn in Dorian mode, or sometimes in Aeolian mode but with a raised sixth. The hymn has an unusual meter of 6-6-6-3-6-6-6-6-6-3. The meter of “What Wondrous Love” derives from an old English ballad about the infamous pirate Captain Kidd:

My name was Robert Kidd, when I sailed, when I sailed;

My name was Robert Kidd, when I sailed;

My name was Robert Kidd, God’s laws I did forbid,

So wickedly I did when I sailed, when I sailed

So wickedly I did when I sailed.

(His real name was William; Americans erroneously called him Robert.)

A popular style of singing during this time was Shape Note Singing, which is a form of singing that uses shapes to denote which pitch should be sung, instead of the traditional European notation that we find in most music now-a-days. In order for the shape note singing to be done correctly, the congregation would be divided into four different sections, and each section was given a different part to sing. This was easier for people to sing, because most people during that time had no idea how to read music, and Shape Note Singing was a way to take something like music and give it to everyone, even the unlearned. The repetitious lyrics also made the text easy to remember.

William Walker (1809-1875)

William Walker was born in Martin Mills, South Carolina in 1807 and grew up just outside of Spartanburg, where, in order to distinguish the difference between himself and other William Walkers, he was nicknamed “Singing Billy.” in 1835 he published a collection of four-shape Shape Note tune books entitled Southern Harmony. This was used for many years and was revised several different times, the final of which was printed in 1854 and is still used today in Kentucky at several different camp meetings. In 1846 Walker published another tune book that was supposed to be used as an index to Southern Harmony. The Publication was entitled The Southern and Western Pocket Harmonist, which contained several different camp meeting tunes. in 1867 Walker published another tune book entitled Christian Harmony where he adopted a new shape notation that contained seven different shapes instead of the traditional four shapes. Christian Harmony shared many similarities with Southern Harmony, but the biggest difference of note was the addition of the Alto harmony in tunes that previously did not contain that particular harmony. William Walker lived a long life, and finally passed away in Spartanburg, South Carolina in 1875. He has an infamy that continues still today with the singing of traditional Shape Note tunes at conventions around the country and especially groups such as the Sacred Harp Singers Of Georgia and Alabama.

In 1952, American composer and musicologist Charles F. Bryan included What Wondrous Love Is This in his folk opera Singin’ Billy, loosely based on Walker’s life as a singing school teacher. In 1958, American composer Samuel Barber composed Wondrous Love: Variations on a Shape Note Hymn (Op. 34), a work for organ, for Christ Episcopal Church in Grosse Pointe, Michigan; the church’s organist, an associate of Barber’s, had requested a piece for the dedication ceremony of the church’s new organ. The piece begins with a statement that closely follows the traditional hymn; four variations follow, of which the last is the “longest and most expressive.” Here is a performance. In 1966, the United Methodist Book of Hymns became the first standard hymnal to incorporate What Wondrous Love.

Here is the St. Olaf choir singing What Wondrous Love. Here is a shape note choir singing the hymn at Berea College. The Germans have taken up shape note singing. Here is a chamber setting for piano and viola and variations for solo viola.

____________________

Thou art the way is by the Episcopal Bishop George W. Doane (1799-1859). “I am the Way, the Truth, and the Life: no man cometh unto the Father, but by Me” (John 14:6). In His sayings which begin “ἐγώ εἰμί, ego eimi, I AM,” Jesus implicitly makes a claim to divinity, because the name of God is יְהֹוָה, YHWH, “I AM WHO AM.” Jesus is the only Way to the Father, because Jesus alone is God and man and unites the two; Jesus is the only Truth, because He reveals the Father and He reveals the ultimate meaning of creation, which is Himself, in whom and for whom the universe was created; Jesus is the only true Life, which death itself could not destroy, and which through His resurrection and the power of the Spirit He pours forth onto a dying world to rescue it from eternal death.

George Washington Doane

George Washington Doane, D.D. was born at Trenton, New Jersey, May 27, 1799, and graduated at Union College, Schenectady, New York. Ordained in 1821, he was Assistant Minister at Trinity Church, New York, till 1824. In 1824 he became a Professor at Trinity College, Hartford, Conn.; in 1828 Rector of Trinity Church, Boston; and, in 1832, Bishop of New Jersey. He founded St. Mary’s Hall, Burlington, 1837, and Burlington College, Burlington, 1846. Died April 27, 1859. Bishop Doane’s exceptional talents, learning, and force of character, made him one of the great prelates of his time. His warmth of heart secured devoted friends, who still cherish his memory with revering affection. He passed through many and severe troubles, which left their mark upon his later verse. He was no mean poet, and a few of his lyrics are among our best. His Works, in 4 volumes with Memoir by his son, were published in 1860. He issued in 1824 Songs by the Way, a small volume of great merit and interest. This edition is now rare. A second edition, much enlarged, appeared after his death, in 1859, and a third, in small 4to, in 1875. These include much matter of a private nature, such as he would not himself have given to the world, and by no means equal to his graver and more careful lyrics, on which alone his poetic fame must rest. The edition of 1824 contains several important hymns, some of which have often circulated without his name. Two of these are universally known as his, having been adopted by the American Prayer Book Collection, 1826:–

Thou art the Way: by thee alone

from sin and death we flee;

and they who would the Father seek

must seek him, Lord, by thee.

Thou art the Truth: thy word alone

true wisdom can impart;

thou only canst inform the mind

and purify the heart.

Thou art the Life: the rending tomb

proclaims thy conquering arm;

and those who put their trust in thee

nor death nor hell shall harm.

Thou art the Way, the Truth, the Life:

grant us that Way to know,

that Truth to keep, that Life to win,

whose joys eternal flow.

Here is the hymnal version.

The tune DUNDEE is by Thomas Ravenscroft (c. 1582 or 1592 – 1635), an English musician, theorist and editor, notable as a composer of rounds and catches, and especially for compiling collections of British folk music.

Little is known of Ravenscroft’s early life. He probably sang in the choir of St. Paul’s Cathedral from 1594, when a Thomas Raniscroft was listed on the choir rolls and remained there until 1600 under the directorship of Thomas Giles. He probably received his bachelor’s degree in 1605 from Cambridge.

Ravenscroft’s principal contributions are his collections of folk music, including catches, rounds, street cries, vendor songs, “freeman’s songs” and other anonymous music, in three collections: Pammelia (1609), Deuteromelia or The Seconde Part of Musicks Melodie (1609) and Melismata (1611). Some of the music he compiled has acquired extraordinary fame, though his name is rarely associated with the music; for example “Three Blind Mice” first appears in Deuteromelia. He also published a metrical psalter (The Whole Booke of Psalmes) in 1621. As a composer, his works are mostly forgotten but include 11 anthems, 3 motets for five voices and 4 fantasias for viols.

As a writer, he wrote two treatises on music theory: A Briefe Discourse of the True (but Neglected) Use of Charact’ring the Degrees (London, 1614), and A Treatise of Musick, which remains in manuscript (unpublished). (Hymnary)

____________________________

Jesus Wept, by James Tissot (1836-1902)

When Jesus wept, the falling tear is a round by William Billings (1746-1800)’ Billings wrote it when he was twenty two, “Jesus wept” – the shortest verse and the most heart-rending in Scripture. Jesus weeps with Mary and Marth and will all who morn, He weeps at the universal death which our guilt has brought upon the world, He weeps at the hardness of heart of His enemies who will seek to kill Him because He raises the dead.

When Jesus wept, the falling tear

in mercy flowed beyond all bound.

When Jesus groaned, a trembling fear

seized all the guilty world around.

William Billings (1746-1800)

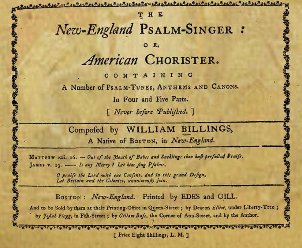

William Billings is probably the best known early American composer. Billings was born in Boston on October 7, 1746. Largely self-trained in music, he was a tanner by trade and a friend of such figures of the American Revolution as Samuel Adams and Paul Revere. Billings’s New England Psalm-Singer (1770), engraved by Revere, was the first collection of music entirely by an American.

Billings wrote for one and only one combination of musical forces: the four-part chorus, singing a cappella. His many hymns and anthems were published in large collections. His music can be at times forceful and stirring, as in his patriotic song Chester; ecstatic, as in his hymn Africa; or elaborate and celebratory, as in his “Easter Anthem”. The latter sounds rather like a miniature Handelian chorus, sung a cappella. As might be expected from a composer who was very close to his roots in folk music, Billings’s music shows a striking purity.

Billings often wrote the lyrics for his own compositions. Like the notes, the words are occasionally awkward but always forceful and vivid. He wrote long prefaces to his works in which he explained (often in an endearingly eccentric prose style) the rudiments of music and how his work should be performed. His writings reflect his extensive experience as a singing master, and often include advice that would wisely be heeded by choral singers today.

Billings’s work was very popular in its heyday, but it failed to last out the composer’s lifetime, and he died in poverty. The Stoughton Musical Society, formed by former students of Billings, has carried on his tradition for over 200 years. As printed in shape notes, Billings’s work has also survived in the musical tradition of the Sacred Harp, where his songs continue to be highly favored by many singers. The modern American composer William Schuman featured Billings’s American Revolutionary War anthem Chester and When Jesus wept in his composition New England Triptych.

New England Triptych was commissioned by Andre Kostelanetz and premiered in 1956. The second movement, “When Jesus Wept,” begins with a solo by bassoon and soon the bassoon is accompanied by oboe. “When Jesus Wept” is a round and uses Billings’ music in its original form. Here it is performed by the Eastman-Rochester orchestra and here by the U. S.Marine Band.

A Long Digression on Shape-Note Singing

With acknowledgment to Keith Willard, Jason Steidl, and others.

The singing of syllables (solmization) to teach students scales & intervals is usually credited to Guido d’ Arezzo (11th century, a six syllable system ut, re, mi, fa, sol, la). In England, by Elizabethan times, this system became simplified to four syllables fa, sol, la, and mi.

A singer would be taught to associate the singing of a given syllable with a particular scale degree. For example the major scale would be sung (while singing the syllables) fa, sol, la, fa, sol, la, mi, fa. This technique was transplanted from Great Britain to colonial America long before any change occurred in the conventional roundhead music notation.

In Puritan colonial America, where, after generations of rejecting choirs and polyphony as a part of “papist” culture, congregational music had gone through a dramatic period of decline.1 Church singing then consisted of lining out music, wherein a leader would sing one line of a psalm or other scripture and the congregation would follow in unison. Reformed leaders intended for this method of congregational singing to give every believer an equal voice and allow all to participate in the simple music. Over time, however, singing had devolved into discord. According to contemporary accounts, by the early 1700s, many congregations knew only a handful of tunes, which they sang very slowly in free rhythm, with very little emphasis on musical agreement. Tunes varied widely from church to church and congregants rarely repeated the same notes of the lined-out hymns together. Unhappy with their musical situation, a group of pastors employed itinerant singing masters to instruct their congregations in days or weeks-long singing schools so that singing might be more agreeable in church services.

In 1801, William Little and William Smith, two singing masters, applied John Connelly’s recently-invented shape-note singing system to their pedagogical book, the Easy Instructor.. Along with naming degrees of the moveable scale “fa,” “so,” “la,” and “mi,” a long-standing part of English musical tradition, they printed their music with the shapes of a triangle, circle, square, and diamond that corresponded to the notes.

The four-shape system is able to cover the full musical scale because each syllable-shape combination other than mi is assigned to two distinct notes of the scale. For example, the C major scale would be notated and sung as follows:

This notation reform which combined music notation with solmization practice ignited the oblong shaped note tunebook golden era (1801 – Civil War). Books such as Repository of Sacred Music, Kentucky Harmony, Southern Harmony, Sacred Harp, Hesperian Harp, and Social Harp were just some of the dozens produced during this era.

Then came the ominous cloud of the “Better Music Movement.” With this movement came the do re mi fa sol la ti do solmization system which had long replaced the simpler fasola system in Europe among the musically literate. In the urban north the victory of Mason and his ilk was complete with the eradication from the churches and communities of such scourges as the “patent” notes and the “crude music” of composers such as William Billings.

Sacred Harp singing originated in the South. The name come from The Sacred Harp (1844), a shape-note tunebook. The South was far more resilient in preserving the old ways. But even the new movement was felt below the Mason-Dixon Line, and thus the seven-shaped note system was born. Southern shaped-note tune compilers largely accepted the belief that the seven syllable (“one for each note”) solmization was superior to the old fashioned fasola approach. Chief among those leading the charge to this trough was “singing Billy Walker” (compiler of the four-shape Southern Harmony) with his seven-note Christian Harmony. Although a variety of seven shape notations were invented, the emerging standard was created by Jesse Aiken.

During the era of late 19th century and the first few decades of the 20th century legions of seven- shape small books were published in southern book mills. The music published in these books were mostly gospel and revival tunes. With the coming of modernity to the rural South this vigorous flood of music publishing dwindled, but continues to this day

Here is a talk on the seven shape system. Here is a talk by Alan Lomax on the emotions that the singing provokes. Here is Old Hundred in the cathedral in Charleston. Here Old Hundred by a congregation in Missouri,showing the seating. Here is some vigorous singing at Goshen, Indiana. And here in Iowa. And in Maine.

The Experience of Singing Shape-Note Hymns

Taking part in a shape-note singing is an experience like no other. Grouped according to vocal range in a square formation, facing the song leader in the center and singing a capella, singers create a powerful sonic exchange.

In Sacred Harp singing, pitch is not absolute. The shapes and notes designate degrees of the scale, not particular pitches. Thus for a song in the key of C, fa designates C and F; for a song in G, fa designates G and C, and so on; hence it is called a moveable “do” system.

When Sacred Harp singers begin a song, they normally start by singing it with the appropriate syllable for each pitch, using the shapes to guide them. For those in the group not yet familiar with the song, the shapes help with the task of sight reading. The process of reading through the song with the shapes also helps fix the notes in memory. Once the shapes have been sung, the group then sings the verses of the song with their printed words.

Sacred Harp songs are quite different from “mainstream” Protestant hymns in their musical style: some tunes, known as fuguing tunes, contain sections that are polyphonic in texture, and the harmony tends to deemphasize the interval of the third in favor of fourths and fifths. In their melodies, the songs often use the pentatonic scale or similar “gapped” (fewer than seven-note) scales.

Sacred Harp singers view their tradition as a participatory one, not a passive one. Those who gather for a singing sing for themselves and for each other, and not for an audience. This can be seen in several aspects of the tradition.

First, the seating arrangement. The singers arrange themselves in a hollow square, with rows of chairs or pews on each side assigned to each of the four parts: treble, alto, tenor, and bass. The treble and tenor sections are usually mixed, with men and women singing the notes an octave apart. This arrangement is clearly intended for the singers, not for external listeners. Non-singers are always welcome to attend a singing, but typically they sit among the singers in the back rows of the tenor section, rather than in a designated separate audience location.

The leader, equidistant from all sections, in principle hears the best sound. The often intense sonic experience of standing in the center of the square is considered one of the benefits of leading, and sometimes a guest will be invited as a courtesy to stand next to the leader during a song.

The music itself is also meant to be participatory. Most forms of choral composition place the melody on the top (treble) line, where it can be best heard by an audience, with the other parts written so as not to obscure the melody. In contrast, Sacred Harp composers have aimed to make each musical part singable and interesting in its own right, thus giving every singer in the group an absorbing task. For this reason, “bringing out the melody” is not a high priority in Sacred Harp composition, and indeed it is customary to assign the melody not to the trebles but to the tenors. Fuging tunes, in which each section gets its moment to shine, also illustrate the importance in Sacred Harp of maintaining the independence of each vocal part.

With the folk music revival of the 1960s and 1970s, inspired in large part by the earlier work of ethno-musicologists such as George Pullen Jackson and Alan Lomax, Sacred Harp singing returned to the northern United States once more, and spread throughout Europe. But all look to the South.

For Sacred Harp singers, the idealized homeland is the South, the bastion of a tradition constantly under attack from powerful cultural forces of assimilation. Singers’ identities are bound to the singing community, which as a strong network reinforces the ethos of the singing culture. Most singers trace their singing heritage through various lines of authority and practice within the tradition. As Kiri Miller writes, “The Sacred Harp diaspora is oriented around descent-based kinship discourses and a strong sense of obligation to a historical and geographical homeland in the South.” In spite of this commitment to tradition, regional styles have developed along different lines of the singing tradition. Some singers from certain regions in the Northeast, for example, often stomp their feet to keep with the fast-paced beat, while singers in the deep South may frown upon such northern enthusiasm as ostentatious excess.

Though Sacred Harp lyrics are explicitly and unapologetically Christian—often in a stark, 18th century sort of way—singers are not necessarily believers It is not uncommon at singings in the Northeast, for example, for the groups to be composed primarily of Jews, Buddhists, atheists, and secular agnostics. These religious signifiers fade away with the singing, however, and friendships easily develop between groups like plainclothes Anabaptist Christians from central Pennsylvania and gay agnostic Jews from Manhattan. As Kiri Miller describes, “Sacred Harp singing today bears the marks of its history as part of an American religious culture that has been disestablished, culturally pluralistic, structurally adaptable, and often empowering from its earliest days.” The affection Sacred Harp singers have for one another overcomes all the distinctions that plague the outside world.

Christian tradition, in both its scriptures and hymnody, encourages a lively imagination about future experiences of heaven and the fulfillment of time. This imagination about heaven, which pervades Christian texts, includes both impassioned singing and the overcoming of identity distinctions that separate humanity on earth—two key elements of Sacred Harp tradition. Psalm 22:27, for example, imagines the eschaton, when “All the ends of the world shall remember and turn unto the Lord: and all the kindreds of the nations shall worship before thee.”

In Revelation 5:7, all of creation joins with the saints to sing God’s praises in heaven. “Then I heard every creature in heaven and on earth and under the earth and on the sea, and all that is in them, singing: ‘To him who sits on the throne and to the Lamb be praise and honor and glory and power, for ever and ever!’” For the Jewish and Christian imaginations, singing is the appropriate response to God’s reign. This takes place where God’s presence dwells and when God’s work has been completed on earth.

For Sacred Harp singers, singing together is heaven, a way to transcendence that breaks down all the earthly barriers that may separate them. It is a participation in celestial realities in the present moment, a powerful and transformative experience that brings unity through a touch of the divine.

____________________

I am the resurrection. These are sentences from the Burial Service of the Book of Common Prayer, set to music by the Elizabethan composer Thomas Morley (1507—1602).

I am the resurrection and the life, saith the Lord:

he that believeth in me,

yea, though he were dead,

yet shall he live.

And whosoever liveth and believeth in me

shall never die.

I know that my redeemer liveth,

and that he shall stand at the latter day upon the earth.

And though after my skin, worms destroy this body,

yet in my flesh shall I see God:

whom I shall see for myself

and mine eyes shall behold,

and not another.

We brought nothing into this world,

and it is certain we can carry nothing out.

The Lord gave and the Lord hath taken away.

blessed be the name of the Lord.

Here it is sung by Ferdinand’s Consort.