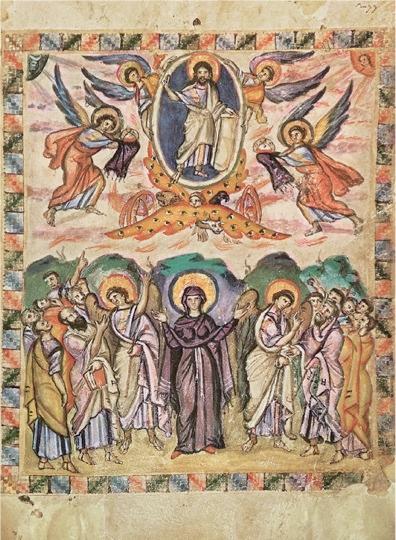

Ascension, Rabbula Gospels, 6th c.

Mount Calvary Church

Eutaw Street and Madison Avenue

Baltimore, Maryland

A Roman Catholic Parish of

The Personal Ordinariate of the Chair of St. Peter

Anglican Use

Rev. Albert Scharbach, Pastor

Easter VII

May 13, 2018

8 AM Said Mass

10 AM Sung Mass

Prelude

Aus tiefer Not schrei ich zu dir, Johann Pachelbel (1653-1706)

Hymns

Love’s redeeming work is done (SAVANNAH)

Let all mortal flesh keep silence (PICARDY)

The head that once was crowned with thorns (ST MAGNUS)

Anthems

Non vos relinquam orphanos, William Byrd

O Rex gloriae, William Byrd

Postlude

Christ lag in Todesbanden, Samuel Scheidt

Common

Missa de S. Maria Magdelena, Healy Willan

___________________________________

Prelude

Aus tiefer Not schrei ich zu dir, Johann Pachelbel

On the harmonium.

_____________________________________

Hymns

Love’s redeeming work is done (SAVANNAH)

Love’s redeeming work is done by Charles Wesley is a cento composed of stanxas ii.-v.,x., of his hymn “Christ the Lord is risen to-day.” Books originating in the Church of England tradition use the tune SAVANNAH, first found in England in John Wesley’s A Collection of Tunes, Set to Music, as they are commonly sung at the Foundery (1742), with the name HERNHUTH, which indicates its origins in 18th-century Moravian books. The name SAVANNAH comes from the Moravian settlement at Savannah, Georgia. Wesley accompanied the Moravians on their voyage from England to Savannah and was deeply impressed by their calm and faith during a storm that panicked the sailors.

1 Love’s redeeming work is done;

fought the fight, the battle won:

lo, our Sun’s eclipse is o’er,

lo, he sets in blood no more.

2 Vain the stone, the watch, the seal;

Christ has burst the gates of hell;

death in vain forbids his rise;

Christ has opened paradise.

3 Lives again our glorious King;

where, O death, is now thy sting?

dying once, he all doth save;

where thy victory, O grave?

4 Soar we now where Christ has led,

following our exalted Head;

made like him, like him we rise;

ours the cross, the grave, the skies.

5 Hail the Lord of earth and heaven!

Praise to thee by both be given:

thee we greet triumphant now;

hail, the Resurrection Thou!

Here is the St Edmundsbury Cathedral Choir. Here is a 1970 version from Guilford Cathedral.

_____________________________________________

Let all mortal flesh keep silence (PICARDY)

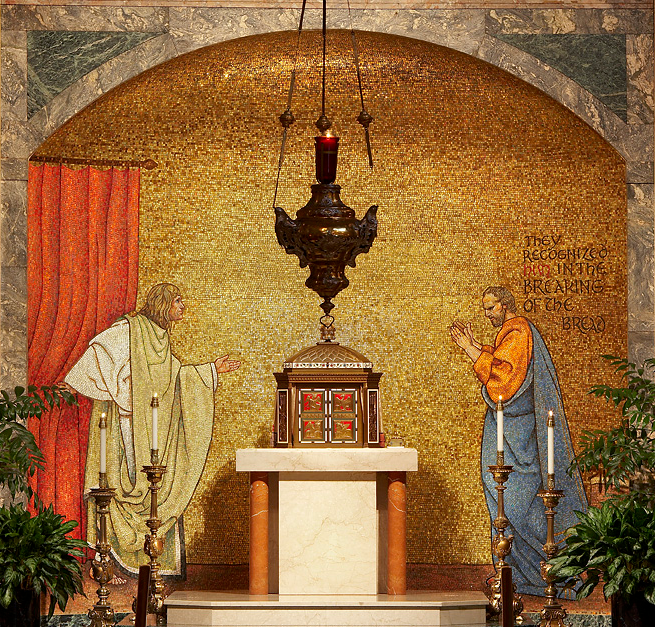

Let all mortal flesh keep silence is a paraphrase by James Moultrie (1829—1885) of the Cherubic Hymn from the Liturgy of St. James of the Eastern Church. The hymn dates to the third century. It is chanted as the bread and wine are carried to the altar. The Greek text reads: “Let all mortal flesh keep silent, and stand with fear and trembling, and in itself consider nothing of earth; for the King of kings and Lord of lords cometh forth to be sacrificed, and given as food to the believers; and there go before Him the choirs of Angels, with every dominion and power, the many-eyed Cherubim and the six-winged Seraphim, covering their faces, and crying out the hymn: Alleluia, Alleluia, Alleluia.” Here is the hymn in the 4th Plagal. Here is the Great Entrance.

Let all mortal flesh keep silence,

And with fear and trembling stand;

Ponder nothing earthly minded,

For with blessing in His hand,

Christ our God to earth descendeth,

Our full homage to demand.King of kings, yet born of Mary,

As of old on earth He stood,

Lord of lords, in human vesture,

In the body and the blood;

He will give to all the faithful

His own self for heavenly food.Rank on rank the host of heaven

Spreads its vanguard on the way,

As the Light of light descendeth

From the realms of endless day,

That the powers of hell may vanish

As the darkness clears away.At His feet the six wingèd seraph,

Cherubim with sleepless eye,

Veil their faces to the presence,

As with ceaseless voice they cry:

Alleluia, Alleluia

Alleluia, Lord Most High

Her is the King’s College, Cambridge, choir.

Gerald Moultrie was a Victorian public schoolmaster and Anglican hymnographer born on September 16, 1829, at Rugby Rectory, Warwickshire, England. He died on April 25, 1885, Southleigh, England.

PICARDY is a hymn tune, based on a French carol; it is in a minor key and its meter is 8.7.8.7.8.7. Its name comes from the province of France from where it is thought to originate. The tune dates back at least to the 17th century, and was originally used for the folk song “Jésus-Christ s’habille en pauvre”. First published in the 1848 collection Chansons populaires des provinces de France, “Picardy” was most famously arranged by Ralph Vaughan Williams in 1906 for the hymn Let All Mortal Flesh Keep Silence.

_________________________________________

The head that once was crowned with thorns (ST MAGNUS)

The Head that once was crowned with thorns was written by Thomas Kelly (1769-1854), who based this hymn on Hebrews 2: 9-10 which speaks of Christ’s glory and the universal message of grace that is available because of Christ’s suffering: “But we see Jesus, who was made a little lower than the angels for the suffering of death, crowned with glory and honor; that he by the grace of God should taste death for every man. For it became him, for whom are all things, and by whom are all things, in bringing many sons unto glory, to make the captain of their salvation perfect through sufferings.”

Kelly employs the poetic device of hypotyposis – a vivid description of a scene or events in words – that provides the singer with a glimpse of the splendor of heaven, which is contrasted with the suffering of the cross and the suffering of all who follow Christ on earth.

1 The head that once was crowned with thorns

is crowned with glory now:

a royal diadem adorns

the mighty Victor’s brow.2 The highest place that heaven affords

is his, is his by right,

the King of kings, and Lord of lords,

and heaven’s eternal Light;3 The joy of all who dwell above,

the joy of all below,

to whom he manifests his love,

and grants his name to know.4 To them the cross, with all its shame,

with all its grace, is given:

their name, an everlasting name,

their joy, the joy of heaven.5 They suffer with their Lord below,

they reign with him above;

their profit and their joy to know

the mystery of his love.6 The cross he bore is life and health,

though shame and death to him;

his people’s hope, his people’s wealth,

their everlasting theme.

Here is the Choir of the King’s School.

Thomas Kelly

Son of a judge, Kelly attended Trinity College (BA 1789) and planned to be a lawyer. After converting to Christ, though, his career plans changed to the ministry. He became an Anglican priest in 1792, but eventually became one of the famous dissenting ministers. He wrote over 760 hymns. Miller’s Singers of the Church (1869) says of him:

Mr. Kelly was a man of great and varied learning, skilled in the Oriental tongues, and an excellent Bible critic. He was possessed also of musical talent, and composed and published a work that was received with favour, consisting of music adapted to every form of metre in his hymn-book. Naturally of an amiable disposition and thorough in his Christian piety, Mr. Kelly became the friend of good men, and the advocate of every worthy, benevolent, and religious cause. He was admired alike for his zeal and his humility; and his liberality found ample scope in Ireland, especially during the year of famine.

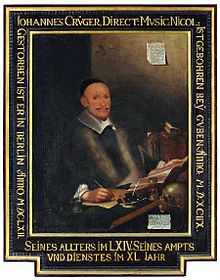

Jeremiah Clarke

The tune ST MAGNUS first appeared in Henry Playford’s Divine Companion(1707 ed.) as an anonymous tune with soprano and bass parts. The tune was later credited to Jeremiah Clark (b. London, England, c. 1670; d. London, 1707), who was a chorister in the Chapel Royal and sang at the coronation of James II in 1685. Later he served as organist in Winchester College, St. Paul’s Cathedral, and the Chapel Royal. He shot himself to death in a fit of depression, apparently because of an unhappy romance. Supported by Queen Anne, Clark was a prominent composer in his day, writing songs for the stage as well as anthems, psalm tunes, and harpsichord works.

Although ST. MAGNUS was originally used as a setting for Psalm 117, it has been associated with this text since they were combined in the 1868 Appendix to Hymns Ancient and Modern. The tune is named for the Church of St. Magnus the Martyr, built by Christopher Wren in 1676 on Lower Thames Street near the old London Bridge, England.

ST. MAGNUS consists of two long lines, each of which has its own sense of climax. The octave leap in the final phrase has a stunning effect, like a vault in a Gothic cathedral.

____________________________________________

Anthems

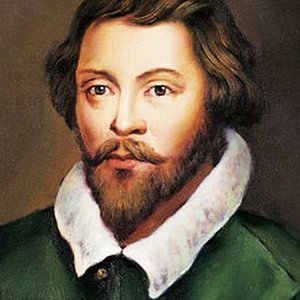

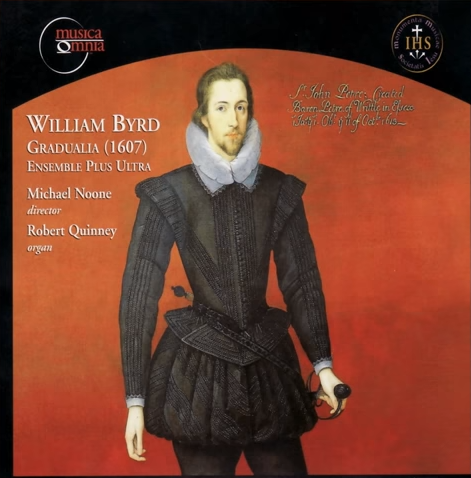

Non vos relinquam orphanos, William Byrd (1540-1623)

Non vos relinquam orphanos. Alleluia. Vado, et venio ad vos. Alleluia. Et gaudebit, cor vestrum. Alleluia.

I will not leave you comfortless. Alleluia. I go, and I will come to you. Alleluia. And your heart shall rejoice. Alleluia.

Here are the Cambridge Singers.

_____________________________________________

O Rex gloriae, William Byrd (1540-1623)

O Rex gloriae, Domine virtutum, qui triumphator hodie super omnes coelos ascendisti; ne derelinquas nos orphanos, sed mitte promissum Patris in nos, spiritum veritatis. Alleluia.

O King of glory, Lord of all power, who ascended to heaven on this day triumphant over all; do not leave us as orphans, but send us the Father’s promise, the spirit of truth. Alleluia.

Here are the New Cambridge Singers.

_____________________________________________

Postlude

Christ lag in Todesbanden, Samuel Scheidt (1587-1634)

Here on the organ.