Jesus and Nicodemus, Crijn Hendricksz Volmarijn (1601-1645)

Mount Calvary Church

Eutaw Street and Madison Avenue

Baltimore, Maryland

A Parish of the Roman Catholic Personal Ordinariate of St. Peter

Anglican Use

Rev. Albert Scharbach, Pastor

Laetare Sunday

March 11, 2018

8:00 AM Said Mass

10:00 AM Sung Mass

Hymns

Rejoice the Lord is king (DARWELL)

The King of Love my shepherd is (ST COLUMBA)

When I survey the wondrous cross (ROCKINGHAM)

Anthems

God so loved the world, John Stainer

Super flumina Babylonis, Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (1525-1594

________________________________________________

Hymns

Rejoice the Lord is king

Rejoice the Lord is King is by Charles Wesley (1707-1788).

The hymn has four principal sources. First, it begins with a clear allusion to Psalm 97:1, 12. Second, the 2-line refrain, with which each verse except the last concludes, begins with a citation of part of the Third Century Eucharistic text, Sursum Corda (‘Lift up your hearts.’). Third, the refrain continues with a reference to Philippians 4: 4. Fourth, the content of the hymn is influenced by that section of the Nicene Creed which deals with Christ’s Resurrection and Ascension, the belief that he will come again as Judge, and the unending nature of his Kingdom.

The final stanza concludes with a modified version of the refrain, in which the words of Sursum Corda are replaced by an allusion to 1 Thessalonians 4:16. This modification may have suggested itself to Wesley because the final verse itself draws upon 1 Thessalonians 4:17.

1 Rejoice, the Lord is King!

Your Lord and King adore!

Rejoice, give thanks, and sing,

And triumph evermore:

Lift up your heart,

lift up your voice!

Rejoice, again I say, rejoice!2 The Lord, our Savior, reigns,

The God of truth and love;

When He has purged our stains,

He took His seat above:

Lift up your heart,

lift up your voice!

Rejoice, again I say, rejoice!3 His kingdom cannot fail,

He rules o’er earth and heav’n;

The keys of death and hell

Are to our Jesus giv’n:

Lift up your heart,

lift up your voice!

Rejoice, again I say, rejoice!4 Rejoice in glorious hope!

Our Lord the Judge shall come

And take His servants up

To their eternal home:

Lift up your heart,

lift up your voice!

Rejoice, again I say, rejoice!

Here is John Rutter’s arrangement.

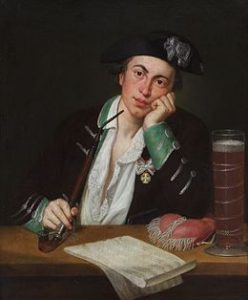

John Darwall (1731-1789) was the son of the rector of Haughton, Randle Darwal. Educated at Manchester Grammar School and Brasenose College, Oxford, he took Holy Orders (deacon 1756, priest 1757), becoming curate of Haughton, and then Bushbury, 1757, followed by Trysull, 1758. He moved to St Matthew’s, Walsall, in 1761, becoming vicar in 1769, and remaining there until his death. He composed tunes for all 150 metrical psalms during the 1760s. He is remembered for the magnificent DARWALL’S 148th, first published in Aaron Williams’s The New Universal Psalmodist (1770).

_____________________________________________

The King of Love my shepherd is

Henry Williams Baker (1821-1877) recast George Herbert’s metrical paraphrase of Psalm 23 into this hymn, The King of love my shepherd is. The true Shepherd -King is Jesus, who cares for His flock by His redemptive death which flows to us through the sacraments. “The streams of living water” flow from Jesus’ pierced side. He ransoms our soul from the captivity of sin, and feeds us with food celestial, “the bread which cometh down from heaven, that a man may eat thereof, and not die.” On our own we never keep to the righteous paths. That is why Jesus comes in love to us, sinners as we are. In his persistent and tender mercy Jesus seeks us, when, “perverse and foolish,” we stray from Him. The wood of the shepherd’s staff is the wood of the cross that guides the strayed soul. Delights flow from Jesus’ pure chalice. The “wine that gladdens the heart” is the Eucharist, the blood of Christ; His is the chalice that overbrims with love. In the Old Testament, our ancestors in faith longed to dwell in the “house of the Lord,” before the revelation of eternal life was clear. But now Christ fulfills that mysterious longing. Jesus is the King who came not be to served but to serve, the one who “giveth his life for the sheep,” the ultimate gift, eternal life with Him.

Here is a Reformed analysis of the hymn:

“We note immediately that the usual way of naming God (“the Lord”) has been replaced with a nonbiblical yet immediately comprehensible allegorical title, “the King of Love.” This unfamiliar opening and the inversion in the first line (“my shepherd is”) prepare the singer for a text that is intentionally—even self-consciously—allusive and aesthetic. This perception of the text is reinforced by the archaic verb forms (“leadeth,” “feedeth”) and the Latinate diction (“verdant,” “celestial”) in the second stanza. The third stanza intensifies the Christological overtones of this paraphrase with allusions not only to the Good Shepherd passage noted earlier but also to Jesus’ parable of the Lost Sheep (Luke 15:4-7; cf. Matthew 18:12-14). The fourth stanza follows the biblical shift from third person to second person, but adds to the images of the shepherd’s rod and staff the suggestion of a processional cross familiar to many nineteen-century Anglican congregations. There is a similar churchy slant in the fifth stanza, where the psalter’s “oil” takes on sacramental tones by being called “unction,” and the usual English translation “cup” becomes a comparably Latinate and ecclesiastical “chalice.” As a result, the reference to God’s “house” in the final line of the sixth stanza does not suggest the Temple in Jerusalem so much as it does the church building in which the hymn is being sung.” (ReformedWorship.org)

I doubt that in the last line “Thy house” is simply the church building; heaven is clearly meant and specified by the “forever.” Anglo-Catholic services are long, but not that long.

1 The King of love my shepherd is,

whose goodness faileth never.

I nothing lack if I am his,

and he is mine forever.2 Where streams of living water flow,

my ransomed soul he leadeth;

and where the verdant pastures grow,

with food celestial feedeth.3 Perverse and foolish, oft I strayed,

but yet in love he sought me;

and on his shoulder gently laid,

and home, rejoicing, brought me.4 In death’s dark vale I fear no ill,

with thee, dear Lord, beside me;

thy rod and staff my comfort still,

thy cross before to guide me.5 Thou spreadst a table in my sight;

thy unction grace bestoweth;

and oh, what transport of delight

from thy pure chalice floweth!6 And so through all the length of days,

thy goodness faileth never;

Good Shepherd, may I sing thy praise

within thy house forever.

Here is the Cardiff Festival Choir singing the hymn. Here is John Rutter’s lovely arrangement with harp accompaniment.

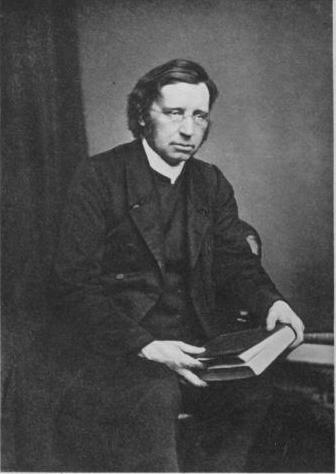

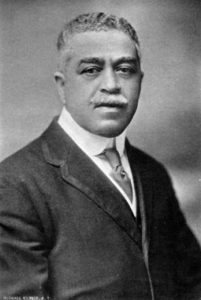

Henry Williams Baker

Sir Henry Williams Baker was the eldest son of Admiral Sir Henry Loraine Baker. Henry was born in London, May 27, 1821, and educated at Trinity College, Cambridge, where he graduated, B.A. 1844, M.A. 1847. Taking Holy Orders in 1844, he became, in 1851, Vicar of Monkland, Herefordshire. This benefice he held to his death, on Monday, Feb. 12, 1877. He succeeded to the Baronetcy in 1851. His hymns, including metrical litanies and translations, number in the revised edition of Hymns Ancient & Modern, 33 in all.. The last audible words which lingered on his dying lips were the third stanza of his rendering of the 23rd Psalm, “The King of Love, my Shepherd is:”—

Perverse and foolish, oft I strayed,

but yet in love he sought me;

and on his shoulder gently laid,

and home, rejoicing, brought me.

This tender sadness, brightened by a soft calm peace, was an epitome of his poetical life.

The tune is ST COLUMBA. Because the compilers of the 1906 English Hymnal were denied permission to use Dykes’s original tune, musical editor Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958) turned to a folk tune that his former teacher Charles Villiers Stanford (1852-1924) had recently edited for a collection of Irish music (A Complete Collection of Irish Music as noted by George Petri (London, 1902-1905); ST. COLUMBA is no. 1043). The two most notable improvements Vaughan Williams made in the hymn tune known as ST. COLUMBA were the lengthening of the second and fourth lines to extend the Common Meter tune to 8787 in order to accommodate Baker’s text—this being their first appearance together—and the use of a triplet (rather than an eighth and two sixteenths) in the sixth measure. (ReformedWorship.org).

_________________________________

When I survey the wondrous cross

Isaac Watts write this hymn for Hymns and Spiritual Songs (1707), Book III, ‘Prepared for the holy Ordinance of the Lord’s Supper’, with the title ‘Crucifixion to the World by the Cross of Christ; Gal. 6.14.’

When preparing for a communion service in 1707, when he himself was thirty-three years old, Watts wrote this personal expression of gratitude for the love that Christ revealed by His death on the cross. Watts echoes Paul: “But far be it from me to glory except in the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ, by which the world has been crucified to me, and I to the world” (Gal 6: 14). The third stanza repeats almost verbatim phrases from St. Bernard of Clairvaux’s hymn “Salve mundi salutare”: such sentiments would be felt by any sincere Christian who meditated upon the crucifixion.

This is one of the greatest hymns on the Passion of Christ, almost certainly the greatest hymn in English on that subject. The singing ‘I’ surveys the crucifixion of Christ, as though from a distance; though reference is made to the blood which is shed, what flows down from ‘his head, his hands, his feet’ is ‘sorrow and love.’ Perhaps in no other English hymn is the use of ‘I’ and ‘me’ less egotistical. The self here is totally centred on the crucified Christ, in whose dying presence gain is loss and pride is contemptible. At the last line, the singer leaves the scene knowing that this ‘amazing’ love demands nothing less than ‘my soul, my life, my all’. That last line should surely be sung, not with confident gusto, but almost silently, with profoundest and almost incredulous reverence.

1 When I survey the wondrous cross

on which the Prince of glory died,

my richest gain I count but loss,

and pour contempt on all my pride.

2 Forbid it, Lord, that I should boast

save in the death of Christ, my God!

All the vain things that charm me most,

I sacrifice them through his blood.

3 See, from his head, his hands, his feet,

sorrow and love flow mingled down.

Did e’er such love and sorrow meet,

or thorns compose so rich a crown?

4 Were the whole realm of nature mine,

that were a present far too small.

Love so amazing, so divine,

demands my soul, my life, my all.

Here is King’s College.

The tune is ROCKINGHAM. Edward Miller (1735 —1807) adapted ROCKINGHAM from an earlier tune, TUNEBRIDGE, which had been published in Aaron Williams’s A Second Supplement to Psalmody in Miniature (c. 1780). Its name refers to a friend and patron of Edward Miller, the Marquis of Rockingham, who served twice as Great Britain’s prime minister. In his version the tune has a fine symmetrical contour, and it can inspire a glowing sense of well-being as it twice sweeps the singers up to the highest tonic.

Miller’s father had made his living laying brick roads, and the young Edward became an apprentice in the same trade. Unhappy with that profession, however, he ran away to the town of Lynn and studied music with Charles Burney, the most prominent music historian of his day. A competent flute and organ player, he was organist at the parish church in Doncaster from 1756 to 1807. Miller was active in the musical life of the Doncaster region and composed keyboard sonatas and church music. His most influential publications were The Psalms of David for the Use of Parish Churches (1790), in which he sought to reform metrical psalmody (and which included ROCKINGHAM), and David’s Harp (1805), an important Methodist tunebook issued by Miller with his son.

__________________________________

Anthems

God so loved the world, John Stainer

God so loved the world that he gave his only begotten Son, that whoso believeth in him should not perish, but have everlasting life. For God sent not his Son into the world to condemn the world, but that the world through him might be saved.

It is from the oratorio The Crucifixion: A Meditation on the Sacred Passion of the Holy Redeemer, composed by John Stainer in 1887.

Here is St Paul’s Cathedral.

John Stainer (1840 – 1901) was an English composer and organist whose music, though not generally much performed today, was very popular during his lifetime. His work as choir trainer and organist set standards for Anglican church music that are still influential. He was also active as an academic, becoming Heather Professor of Music at Oxford.

Stainer was born in Southwark, London in 1840, the son of a cabinet maker. He became a chorister at St Paul’s Cathedral when aged ten and was appointed to the position of organist at St Michael’s College, Tenbury at the age of sixteen. He later became organist at Magdalen College, Oxford, and subsequently organist at St Paul’s Cathedral. When he retired due to his poor eyesight and deteriorating health, he returned to Oxford to become Professor of Music at the university. He died unexpectedly while on holiday in Italy in 1901.

____________________________

Super flumina Babylonis, Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina

Super flumina Babylonis illic sedimus et flevimus, cum recordaremur Sion. In salicibus in medio ejus suspendimus organa nostra.

By the waters of Babylon we sat down and wept: when we remembered thee, O Sion. As for our harps, we hanged them up: upon the trees that are therein.

Here is St. Luke’s Ordinariate Church in Washington. Here is the Collegium Musicum – Coro e Orchestra dell’Università di Bologna.

Palestrina’s four-voiced Super flumina babylonis was first printed in his second book of motets. This 1581 volume, from the Gardano press in Venice, contains a large number of his most popular works, some of which must have graced the liturgy of the papal chapel for many years. As is common in Palestrina’s motet style, each phrase of his text receives one musical phrase; several begin with classic Points of Imitation. The Psalm text, however, paints the extraordinarily somber image of the Israelites in captivity: they sit by the side of the rivers in Babylon and hang up their harps, unable to sing in this strange country. Palestrina responds to this text by allowing each voice to sing the first melody in the mournful Hypophrygian mode. There follows a phrase about the Israelites’ weeping, and the composer sets it to an uncharacteristically chromatic series of chords, flats following sharps. This is not his usual “perfection!” A second imitative passage, again to a downward-leading melody, speaks of the memory of lost Zion. The last and longest phrase of the piece actually contains two musical puns. At the word suspendimus (we hang), Palestrina gives each voice a melody just like a common “suspension” figure. In Latin, the object of the hanging is the organa; here he writes a clever evocation of “ancient music,” or organum.

Both in his life and after, Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina was renowned for the perceived perfection of his style. Legends quickly grew that he had “saved church music” during the Council of Trent, and the papal choir continued singing his music for centuries after his death. The seventeenth century viewed the “Palestrina style” as antique, but classical and still worthy of emulation; it remained an active musical language in the eighteenth. The nineteenth century’s Cecilian movement sought to reclaim church music’s Golden age by revisiting Palestrina’s music, and in the twentieth, the early music revival gave him yet another vogue. Each era has looked at Palestrina’s music and seen something that is balanced and pure, that deals judiciously with dissonance, and that carefully molds each phrase into an elegant arch. This is not to call his music bland; Palestrina was perfectly capable of writing poignant and affective melodies as well as classically elegant ones. He also frequently used subtle “madrigalisms” to paint the nuances of his text. All these elements of style are present together in one of his more famous motets, Super flumina babylonis.